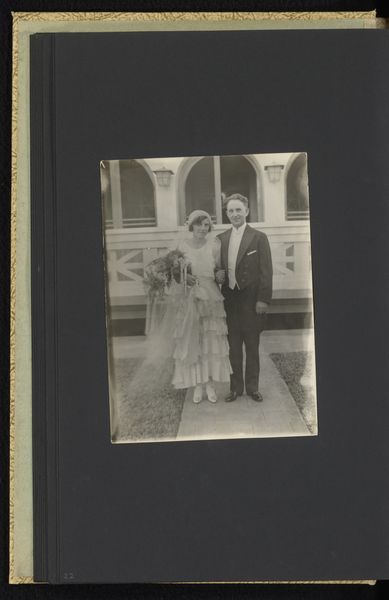

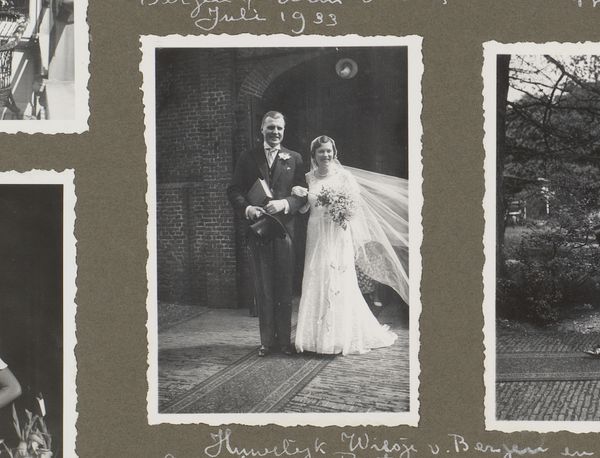

photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

still-life

#

wedding photograph

#

wedding photography

#

archive photography

#

photography

#

historical photography

#

couple photography

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

realism

Dimensions: height 135 mm, width 85 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Immediately striking, isn't it? "Photographs from the Estate of Isabel Wachenheimer," potentially from 1946, rendered as a gelatin-silver print. The surface texture suggests its history; handling and age have visibly marked the piece. Editor: There's a beautiful simplicity to it. Stark contrast, almost harsh. It's incredibly direct in its subject—a newly married couple—but there's a poignancy I can’t quite articulate. They’re positioned so formally, almost stiffly. Curator: The materiality contributes, certainly. Gelatin-silver prints, especially from that era, speak to a specific type of photographic production and consumption. They were, at one point, ubiquitous; documenting everyday lives but now exist as valued artifacts. We often frame photos and photography as ‘art,’ while it begins primarily as the recording of a personal life event like a wedding. Editor: Right. Seeing this now, displayed as an art object, it begs the question of its original intent versus its current interpretation. A wedding photo in 1946 signifies so much about societal expectations and the role of women post-war. This image participates in the normalization of a family, or an aspiration to belong. And who was Isabel Wachenheimer? Curator: That's exactly it! This photo also emphasizes labor—from the manufacturers of the gelatin-silver print materials, to the labor of the photographer capturing and developing the images, and finally the workers who manufactured the wedding dress. This speaks to the wedding industry that was starting to gain its footing, as opposed to wedding dresses made and crafted at home by family or friends. Editor: You are spot on in noticing all the labor put into the construction and circulation of the wedding. There is also an institutionalization in wedding photography itself. As a genre it carries enormous social weight. These kinds of formal images broadcast family status. The specific framing—the couple in front of that somewhat stark backdrop—conveys so much about class and expectations. This all affects how this photography is displayed and how a wider public understands the genre of “archive photography” today. Curator: Considering the history, and the print itself, brings out the nuances layered beneath the simple surface. Thank you. Editor: And thank you, thinking about these kinds of weddings and weddings photography help inform my ideas of archives today.

Comments

rijksmuseum over 2 years ago

⋮

Isabel Wachenheimer still signed with her concentration camp number, ‘K.Z. häftling No 918’ three months after she was liberated. Just see the inscription on the back of a portrait photograph of her taken on 25 September 1945. Isabel was a broken person after the war. She slowly recuperated from a fractured vertebra in Davos (Switzerland). In November 1946 Isabel married Leo Blumensohn, a fellow victim she met in the Westerbork transit camp.

Join the conversation

Join millions of artists and users on Artera today and experience the ultimate creative platform.