print, engraving

# print

#

landscape

#

romanticism

#

19th century

#

history-painting

#

engraving

#

watercolor

Dimensions: sheet: 47.9 x 68.1 cm (18 7/8 x 26 13/16 in.)

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

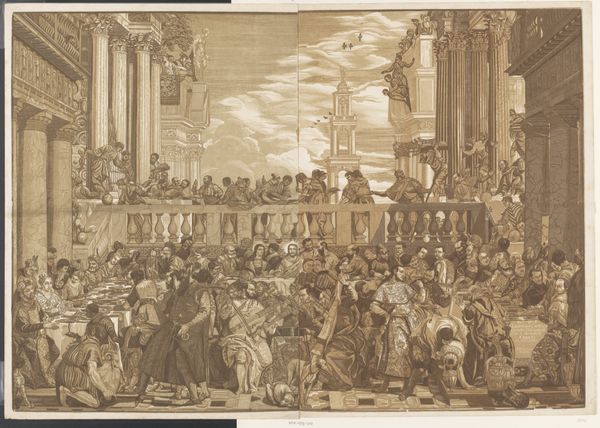

Curator: The scale of this engraving, John Martin's "Belshazzar's Feast" from 1826, is simply astonishing. It's almost cinematic, wouldn't you agree? Editor: Immediately! It has that foreboding sense of grandeur. The chiaroscuro effect, alternating radiant light with deep shadows, gives it an almost theatrical, stage-like quality. Like a nightmare unfolding on a cosmic stage. Curator: Martin was deeply interested in depicting cataclysmic events from the Bible. The story of Belshazzar’s Feast, as recounted in the Book of Daniel, concerns a king who profanes sacred vessels and is punished by a divine message foretelling his kingdom's demise. Martin exhibited it in London in 1826, at a time when biblical narratives were used to critique contemporary society. Editor: Look at the pervasive imagery. The Tower of Babel looming in the background… and on the opposite side the menorah which the Jewish King was meant to protect, this points to colliding religious forces. This is the clash of empires depicted on one terrifying page. And the figures reacting to the writing on the wall – a common image to suggest an unavoidable and unfortunate outcome. Curator: Absolutely, this reflects an anxiety about divine judgment and national decline during a period of social and political reform in Britain. Martin's audience would've certainly been aware of the decline of other empires, or thought they would meet such a fate. Editor: I wonder if those luminous beams can be read as anything more than mere light... It could be argued that its presence reinforces this as a scene from revelation itself. That kind of "divine light" as ultimate judgement and destruction, but that kind of apocalyptic image was certainly en vogue at the time. Curator: Martin found ways to capitalize on it. Mass print production brought works like this, laden with social commentary and anxiety, to a wide audience. It's easy to forget the effect this print would have had. To be surrounded by biblical painting after biblical painting could bring such narratives of past disasters and hold them up against British rule. Editor: It’s quite amazing to me how potent visual symbols, like that illuminated text, tap into deep wells of cultural understanding, even now, centuries later. Curator: Indeed. Understanding Martin's place within the socio-political discourse of 19th-century England gives us so much context to appreciate this artwork. Editor: I concur, examining his effective use of iconic and symbolic weight, enriches our interpretation and offers new perspectives.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.