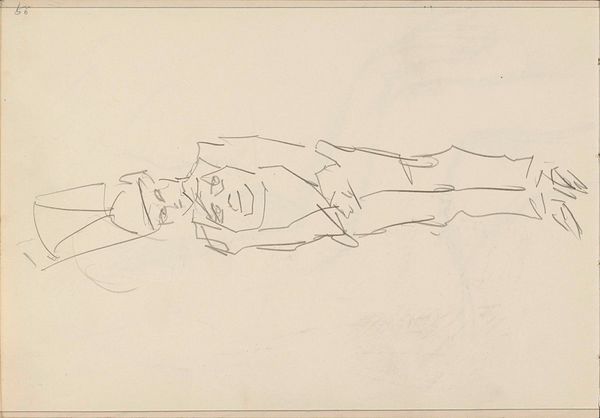

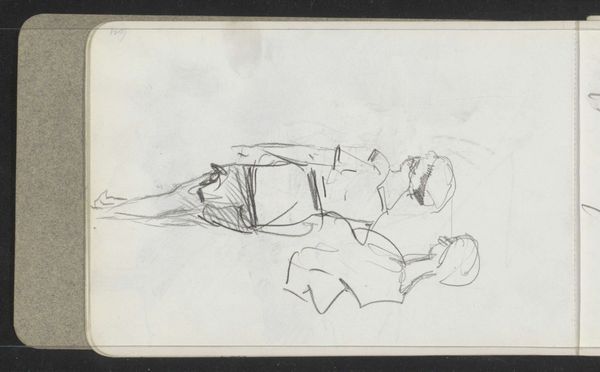

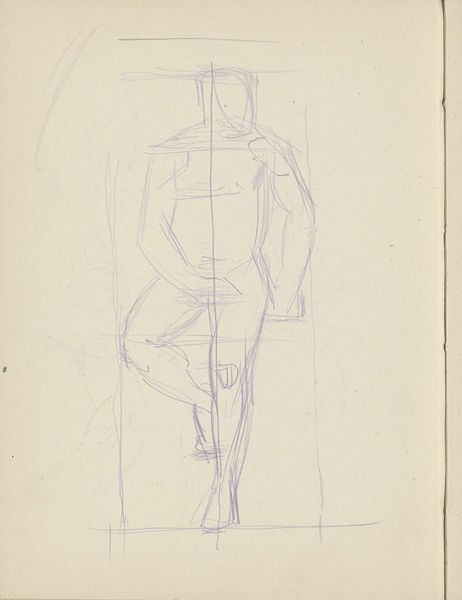

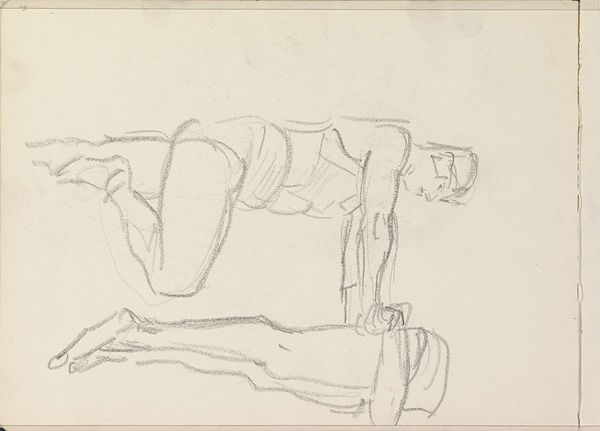

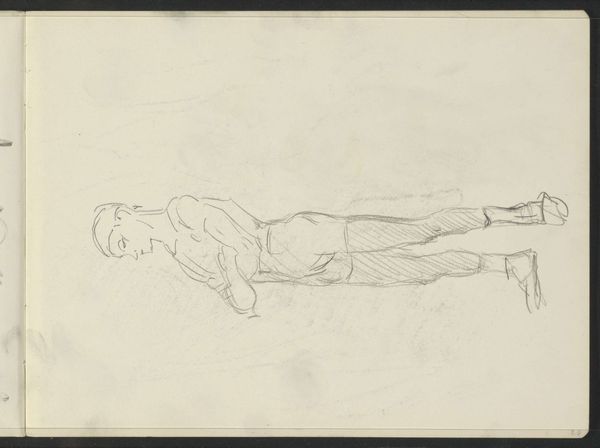

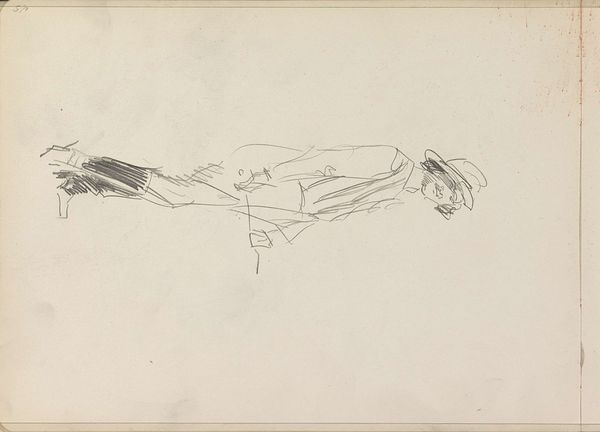

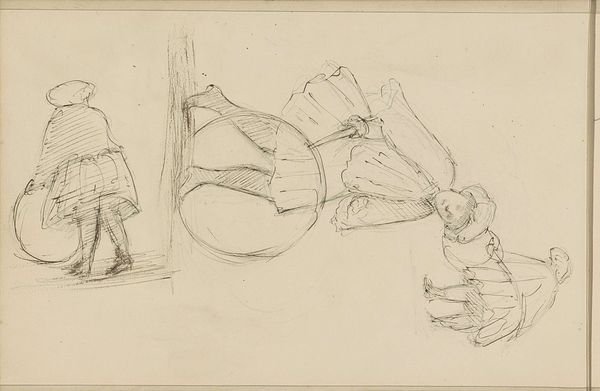

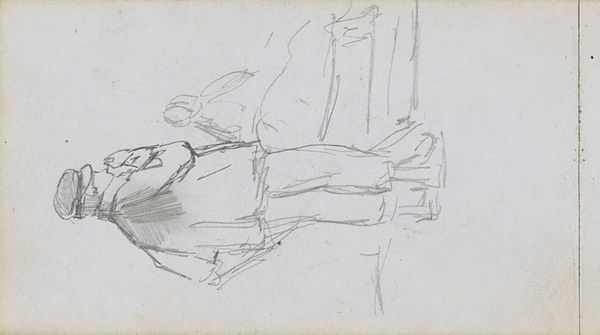

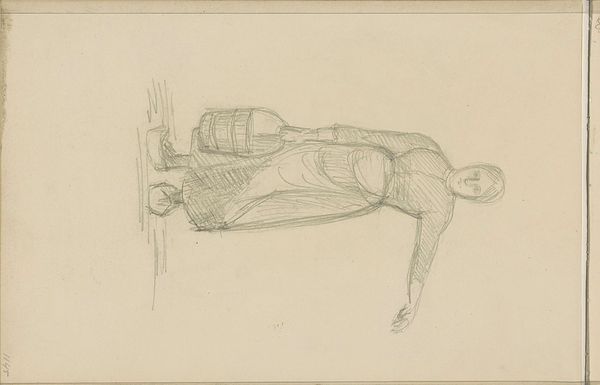

drawing, pencil

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

figuration

#

pencil

#

academic-art

#

realism

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: Here we have Jozef Israëls' "Zittende jongen met een hoed en klompen," a pencil drawing dating from 1834 to 1911. The stark simplicity of the lines makes me feel like I’m looking at a fleeting memory. What catches your eye when you examine this drawing? Curator: The immediate presence of the planar relationships is compelling, is it not? The spatial organization achieved through line weight alone; see how the density of hatching defines form and simultaneously fractures it? The hat, for instance, isn’t merely described, but constructed by the very act of drawing. Editor: So you’re focusing on how the lines themselves create the image? I hadn’t thought of it that way. I was looking more at what the lines represent: the boy, his clothes… Curator: Representation is, of course, present, but subordinate to the visual vocabulary at play. Consider how Israëls uses the negative space, or lack thereof. The boy almost blends with the paper itself. What does that imply formally? The figure’s groundedness, perhaps? Or the lack of clear distinction between subject and ground? Editor: I see what you mean. The way the lines almost disappear makes the boy feel less defined. Is this something Israëls did often? Curator: Analyzing this work in isolation reveals its unique formal properties. We must attend to the internal structure of the drawing itself. That’s what determines its artistic value and differentiates it from mere illustration. Editor: This close visual analysis makes me see the drawing in a whole new light. It’s more than just a picture of a boy; it's an exploration of line and form. Curator: Precisely. Each line performs a dual function, descriptive and constructive. Through this rigorous approach to seeing, the artwork becomes a self-contained world of visual experience.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.