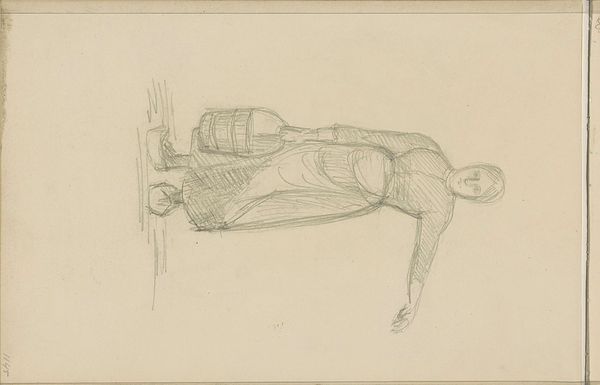

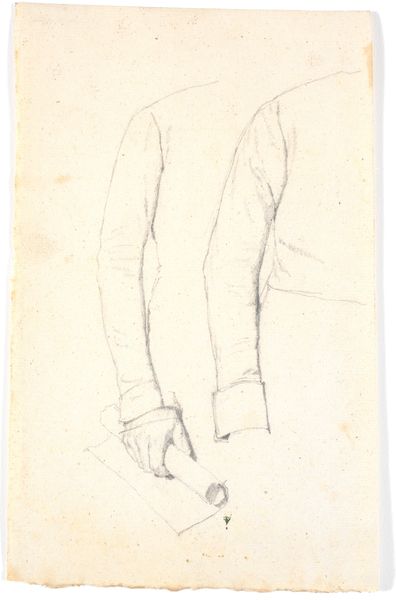

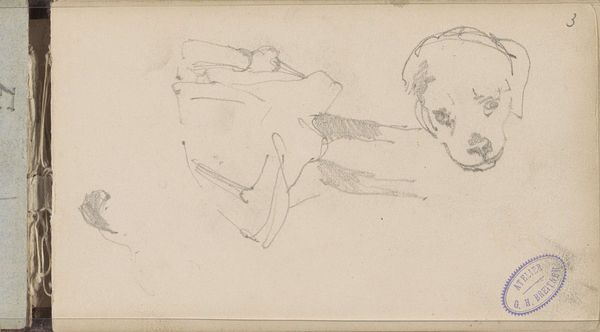

drawing, paper, pencil

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

amateur sketch

#

toned paper

#

light pencil work

#

pencil sketch

#

figuration

#

paper

#

personal sketchbook

#

idea generation sketch

#

sketchwork

#

detailed observational sketch

#

pencil

#

sketchbook drawing

#

sketchbook art

#

realism

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

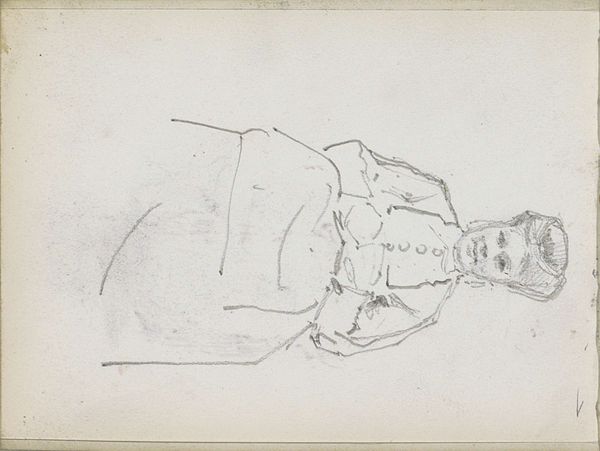

Curator: We’re looking at “Zittende jongen met een emmer,” or "Sitting Boy with a Bucket", a pencil drawing on paper attributed to Jozef Israëls. The Rijksmuseum places it sometime between 1834 and 1911. Editor: Well, right off the bat, I feel like I’ve stumbled into someone’s private thoughts, you know? Like finding a page ripped from a sketchbook. It’s so raw. Curator: Exactly! Israëls was deeply invested in Realism, a movement which often championed the lives of the working class. We can analyze this sketch as a social commentary, exploring the realities of labor and childhood. It humanizes a class often overlooked. Editor: It’s interesting you mention that. There’s an innocence here that’s disarming. I almost feel like I am intruding on this kid’s… boredom, maybe? He’s just… existing. There's nothing romanticized about it, which, yeah, rings true. No heroic posing, no theatrical lighting. Curator: The light pencil work and toned paper create an interesting dynamic too, because Israëls style often captured the moodiness, a certain somber reflection of Dutch life. Editor: Mmm, totally, I see it now. The loose lines add to that feeling, you know? Like it's unfinished, transient. Makes you wonder about his story, like, where is he sitting? What's in the bucket? It sparks a million questions, this little sketch. I also like the fact that the background has been left unaddressed; it makes you concentrate more on the foreground. Curator: Considering the period, it speaks volumes about Israëls focus. Instead of grand historical scenes or idealized portraits, he turns to everyday existence, giving it validity. Editor: It feels very… intimate, don’t you think? It could be seen as incomplete, or… deliberately revealing? Makes it hard to not project your own story onto his face. Curator: And within an intersectional framework, the work subtly challenges established art hierarchies. By sketching the everyday, Israëls is placing the life of this anonymous boy on par with, say, nobility. Editor: You’re so right. Well, this was deeper than I thought a quick little sketch could get! Curator: It is, isn't it? Sometimes the smallest works carry the largest conversations.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.