#

aged paper

#

toned paper

#

homemade paper

#

sketch book

#

personal sketchbook

#

sketchbook drawing

#

watercolour bleed

#

watercolour illustration

#

sketchbook art

#

watercolor

Dimensions: height 103 mm, width 155 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

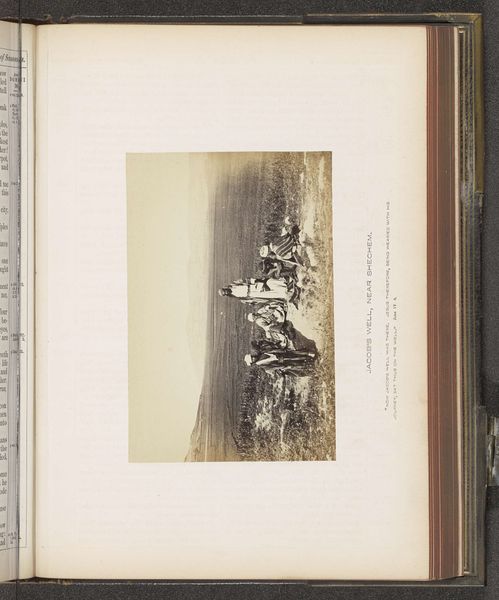

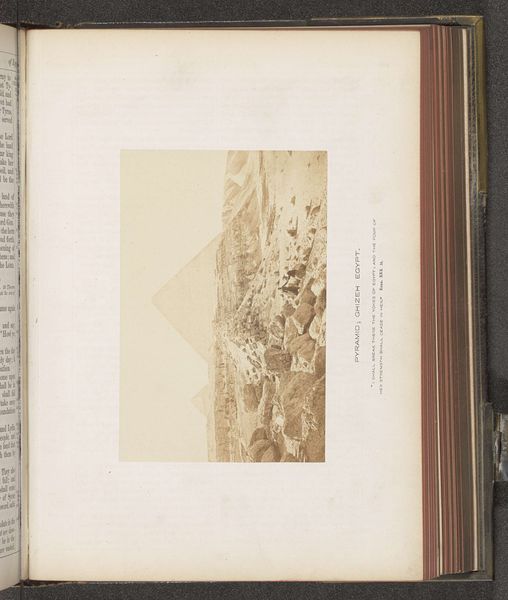

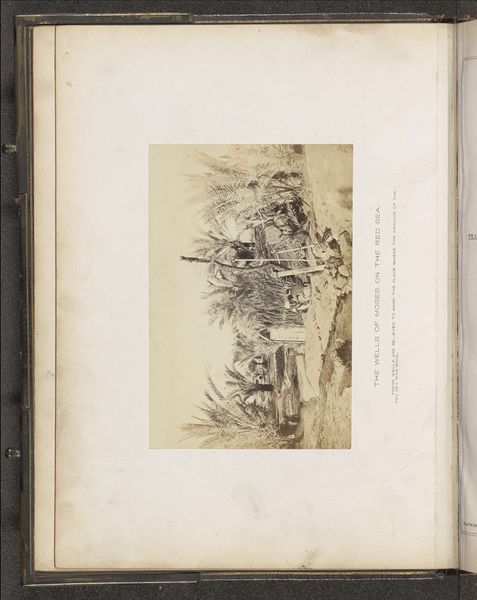

Curator: Looking at Francis Frith's "View of Jerusalem from the Mount of Olives," circa 1850-1865, currently held in the Rijksmuseum, I'm immediately struck by how small and fragile it seems. It's contained within the pages of what appears to be a personal sketchbook. Editor: There's an intimacy to it, seeing the cityscape rendered in watercolor with this bleed. I'm struck by its slightly melancholic feel. The chosen viewpoint and muted palette evoke a sense of quiet contemplation, maybe even a lament. Curator: Precisely. Frith's presence in the Middle East during that time was tied to larger imperial projects and the Orientalist gaze. His photographs often depicted a romanticized and somewhat colonialist vision of the region. Understanding that is key to interpreting this more informal work. It’s like seeing behind the curtain. The materials – the homemade, aged paper, and the humble watercolour medium - humanizes a complicated legacy. Editor: The sketchbook format, too, changes how we perceive Frith's documentation. Rather than a polished photograph intended for wide consumption, it feels like a personal record, perhaps a moment of private reflection amidst a period of significant social and political upheaval. You can feel his hand in it – not just the hand of the photographer, but of a craftsman. The production involved travel, physical work on-site, choice and deployment of his instruments, his skilled hand on paper... It pushes the discourse beyond the art object into material production. Curator: And even further when you consider who might have accessed that sketchbook then, and how it's accessible to us now. Was this simply a document of colonial exploration or did the embodied artistic choices carry different intent? Frith’s biography tells of an anti-slavery activist as well as photographer and businessman. The complexity within an image like this should provoke meaningful questioning. Editor: Absolutely. It’s a poignant reminder that even within seemingly straightforward depictions, there are layers of socio-political contexts and lived labor that inform the materials. The act of creating this image speaks volumes about nineteenth-century production and access. Curator: I come away with a deeper understanding of the image’s place within a very specific history. Editor: And I appreciate its humble materiality and the hands it took to create it all the more.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.