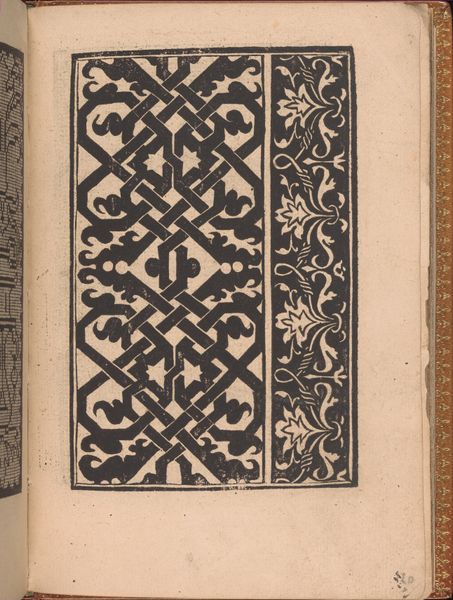

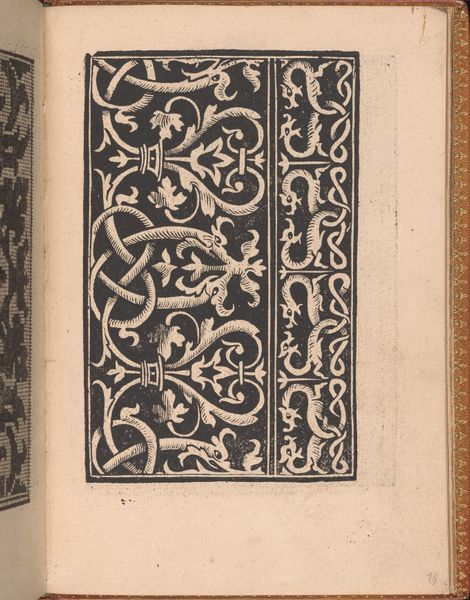

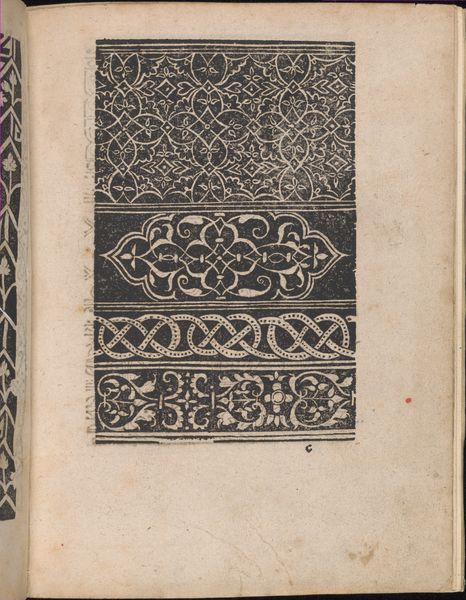

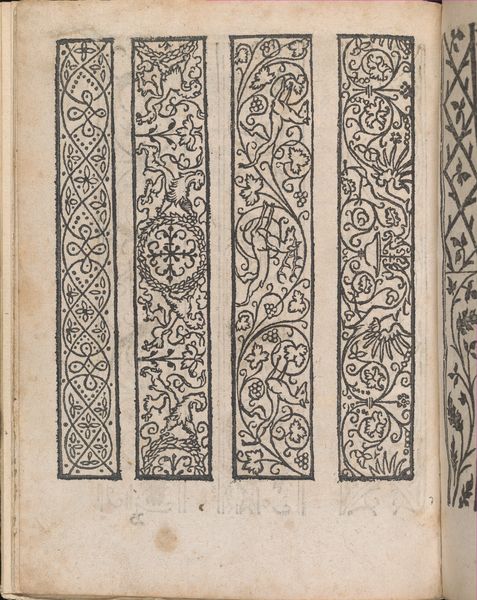

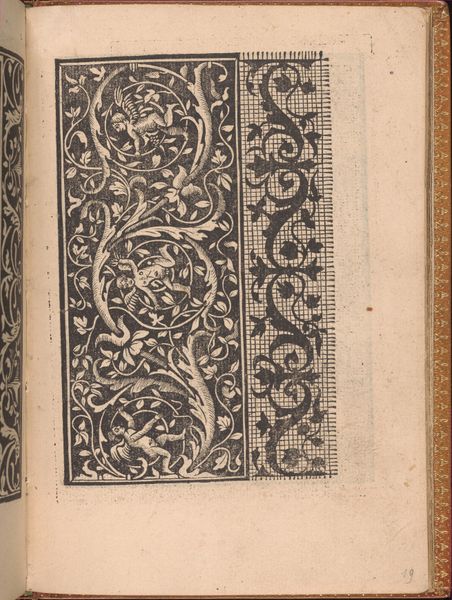

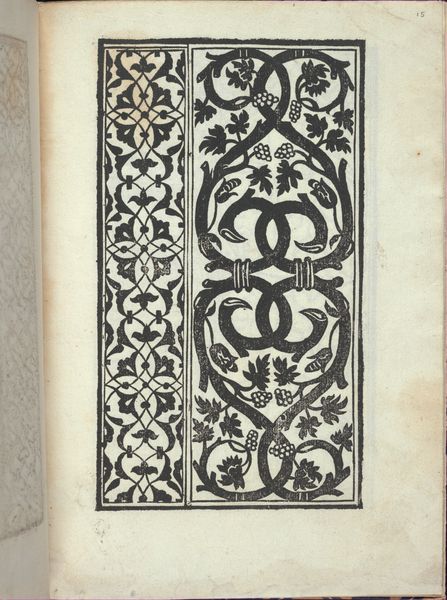

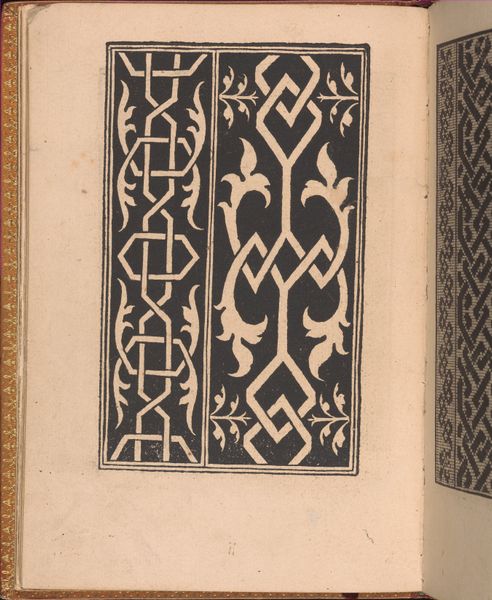

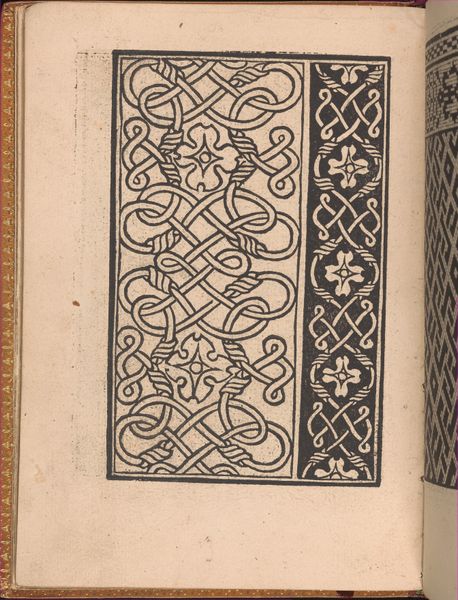

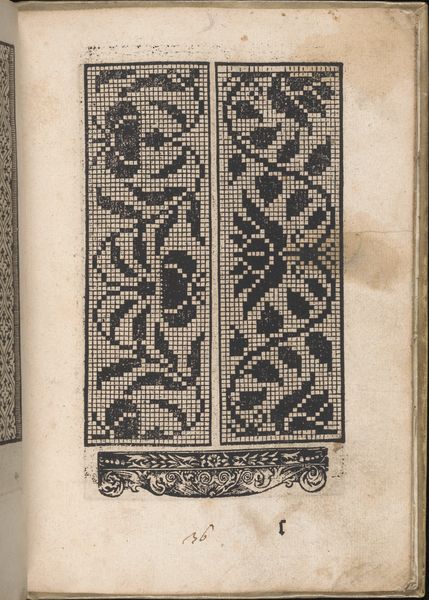

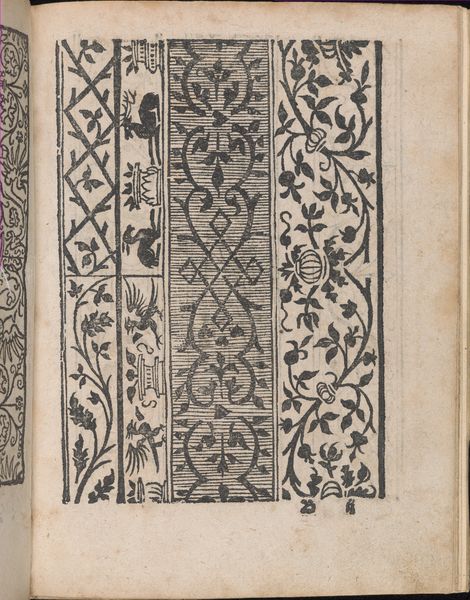

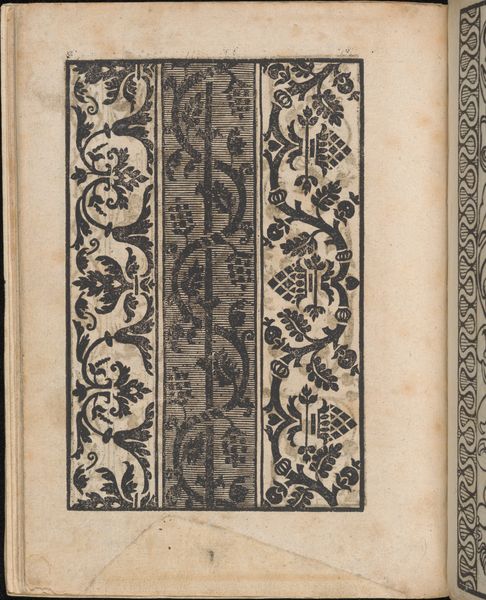

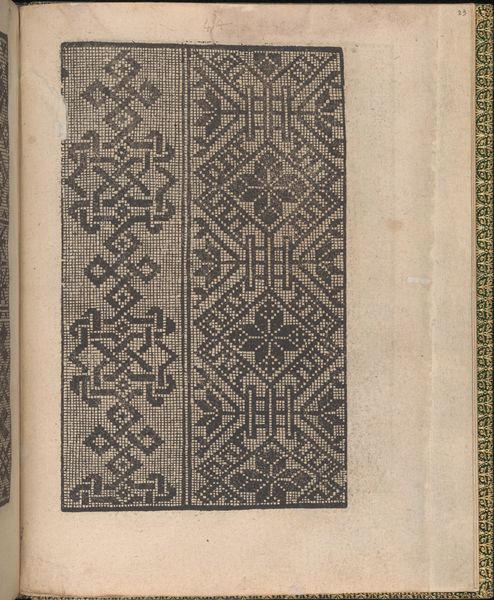

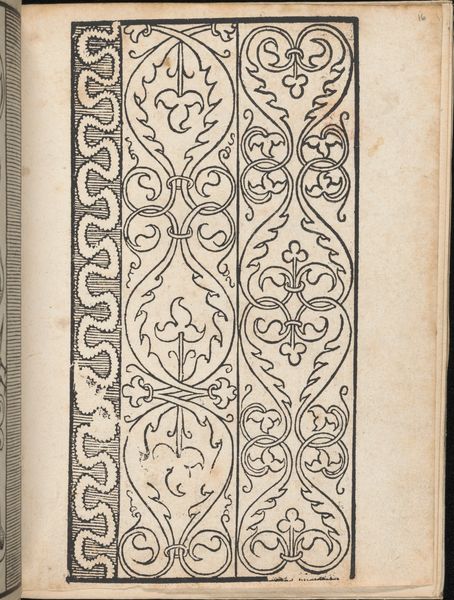

drawing, print, ink, woodcut, engraving

#

drawing

#

medieval

#

pen drawing

#

ink paper printed

# print

#

book

#

ink

#

linocut print

#

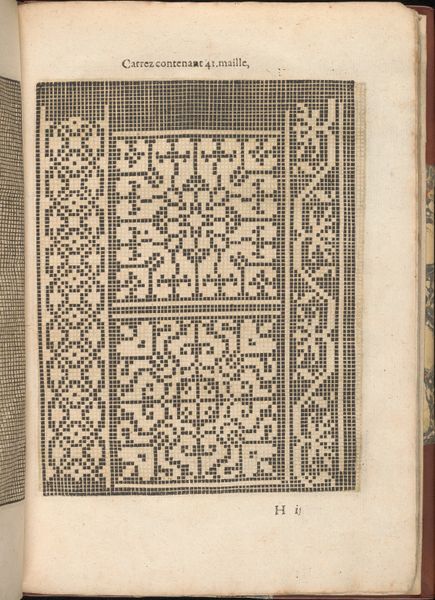

geometric

#

woodcut

#

line

#

decorative-art

#

engraving

Dimensions: Overall: 7 7/8 x 5 1/2 in. (20 x 14 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Editor: Here we have "Convivio delle Belle Donne, page 8," a print from 1532 by Nicolò Zoppino, held at the Met. The stark black and white geometric patterns remind me a bit of textiles. How do you see this piece? Curator: The patterns, especially in prints like these, become crucial clues to understanding not just aesthetics, but production and labor. The woodcut, the carving – it’s a skilled artisan’s hand that dictates those lines. The crispness hints at the value placed on precise labor and the dissemination of aesthetic ideas in the Renaissance. Do you think the pattern's purpose changes when reproduced like this? Editor: That's interesting. It does seem like something originally handcrafted becomes more of a commodity once it’s printed, potentially losing some of its uniqueness in the process of wider distribution. What can this artwork tell us about society at the time it was produced? Curator: We could consider the status of books and printed materials as they began to replace other forms of craft. This brings to mind the labor behind creating the paper, the ink, and the press itself. Printing created opportunities and shifted economic structures. The question of access becomes central, doesn’t it? Who could afford these printed books, and what kind of knowledge did they convey? Editor: So, focusing on materials and the printing process gives us a much clearer idea of its cultural impact! I’ll definitely be thinking more about production when looking at prints from now on. Curator: Absolutely. By considering the labor and materials, we're looking at art not just as an object, but as part of a complex network of social relations and economic forces.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.