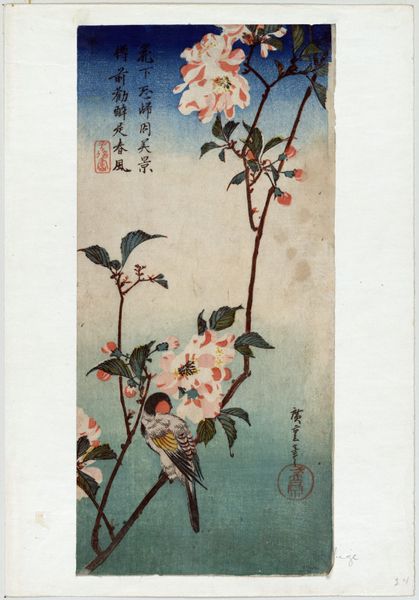

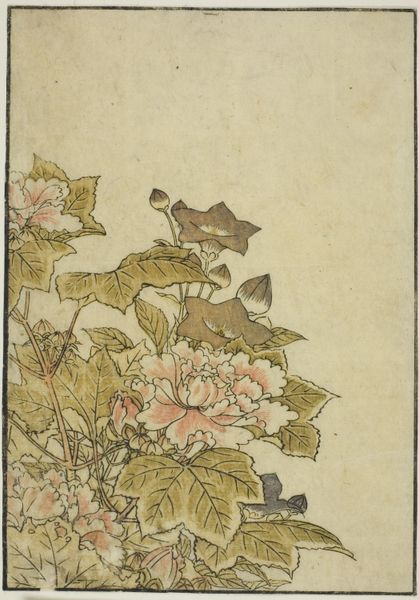

print, ink, woodblock-print

# print

#

asian-art

#

landscape

#

bird

#

ukiyo-e

#

japan

#

ink

#

woodblock-print

#

nature

#

botanical art

Dimensions: 13 3/16 × 8 11/16 in. (33.5 × 22 cm) (image, vertical ōban)

Copyright: Public Domain

Editor: This woodblock print, titled "Blue Bird and Pink Flowers," is attributed to Nakayama Sugakudo and was possibly created around 1859. I’m struck by how the leaves seem to overwhelm the flowers and the bird; it feels… unbalanced. What aspects of this print stand out to you? Curator: The ukiyo-e tradition often depicted scenes of everyday life and nature, but I'm immediately drawn to the *means* of its production. Woodblock printing was a collaborative, laborious process. What do you imagine were the social dynamics of the workshop creating these prints, especially in regard to the hierarchy among designers, engravers, and printers? Editor: I hadn’t considered that! Was there a hierarchy within the production? It feels as though everyone contributed in a collaborative effort, although someone might have had final sign off of the overall finished work. Curator: Precisely. The designer received initial acclaim but often remained relatively anonymous, while the artisans, engravers, and printers whose skilled labor made the images tangible, had considerably lower status, and were bound by specific contractual arrangements with publishers. How might an awareness of that labor and class structure shift our understanding of the image’s seemingly innocent depiction of nature? Is it merely a landscape study, or does it represent a specific market desire of those commissioning or purchasing it? Editor: It sounds much less innocent now. To think that its beauty belies those production relationships and its potential use as a symbol of social standing. Curator: Exactly. Even the choice of ink and paper – where did those materials come from? Were they readily available or costly imports? Considering the entire production line adds another layer of meaning. What new insights have you gained? Editor: The artwork made me initially reflect upon its composition, but considering its production, it reframes how I perceive and interpret it and makes me think about what type of person acquired it in 1859. It gives me a greater appreciation for everyone's role in the workshop in that particular moment in time. Curator: Yes, appreciating the physical production and its cultural place makes art history so much more grounded in reality.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.