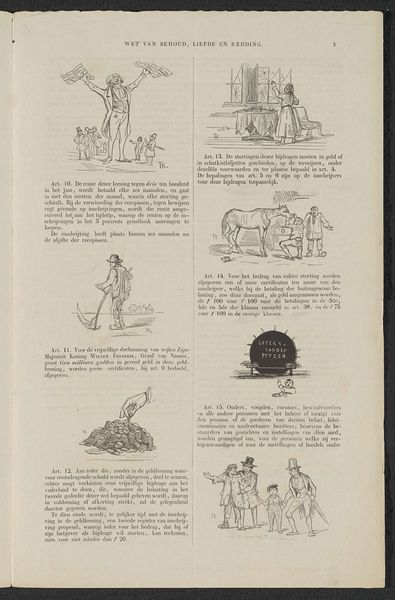

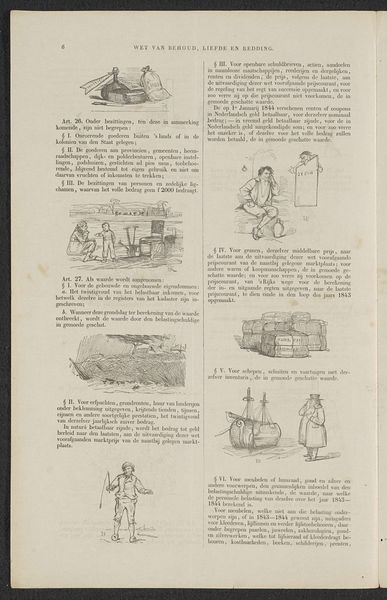

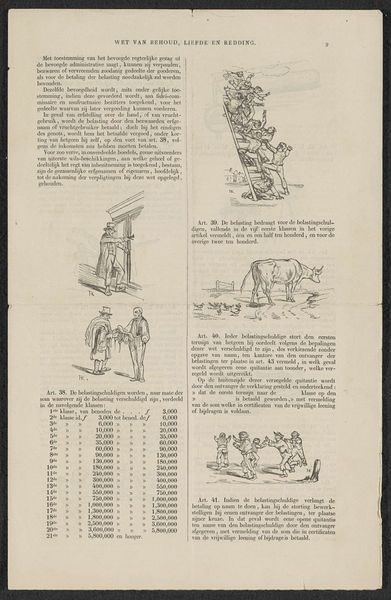

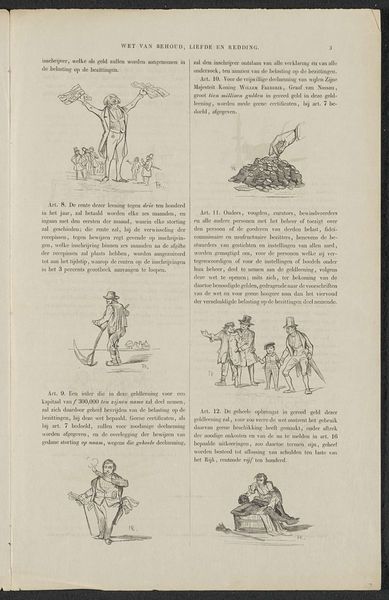

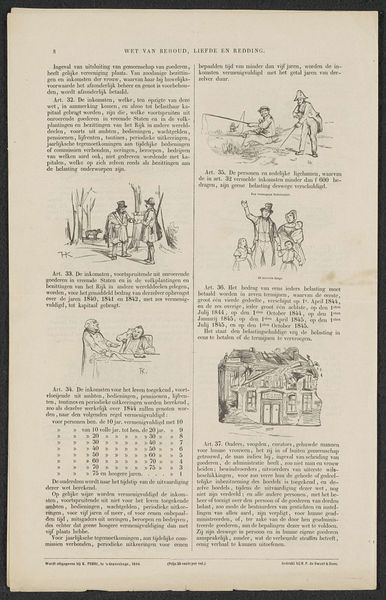

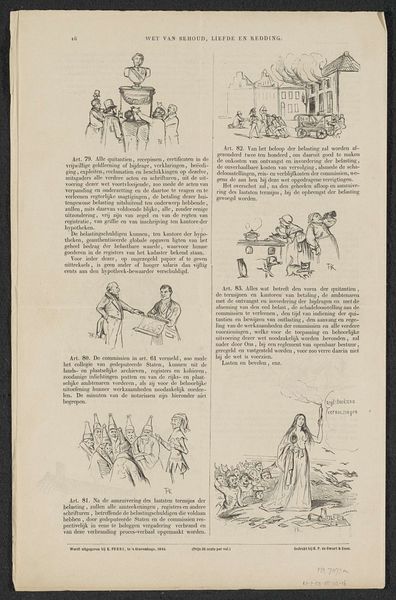

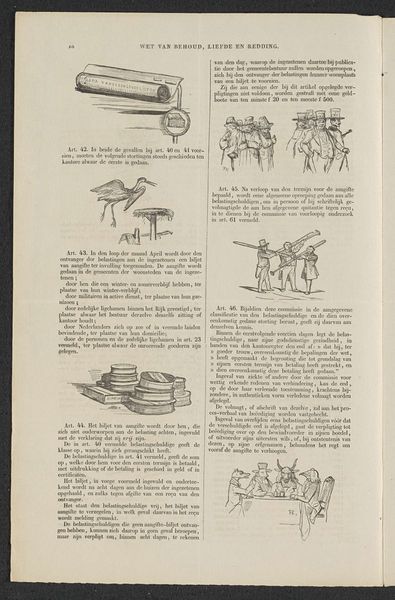

Herdruk van de satire op de aansporing tot deelneming in de (zogenaamde) vrijwillige 3% geldlening van 1844 (blad 15) 1844

hermanfrederikcareltenkate

Rijksmuseum

print, engraving

dutch-golden-age

history-painting

engraving

Dimensions: height 385 mm, width 245 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This rather complex image, housed at the Rijksmuseum, is a print entitled "Herdruk van de satire op de aansporing tot deelneming in de (zogenaamde) vrijwillige 3% geldlening van 1844 (blad 15)," dating back to 1844 and created by Herman Frederik Carel ten Kate. It's an engraving, exhibiting characteristics reminiscent of the Dutch Golden Age, but deployed here for the specific function of historical satire. Editor: It feels like a legal document illustrated by a slightly manic cartoonist. The tiny figures and cramped composition create a sense of… oppressive bureaucracy? Or perhaps chaos barely contained by order. Curator: That's a good starting point. The chaos stems from its purpose. It satirizes the government's attempt to encourage voluntary participation in a 3% loan in 1844. Ten Kate utilizes the visual language and tropes we often associate with the Dutch Golden Age—specifically its satirical printmaking—to critique contemporary government policy. This intersection is key. Editor: So, a deliberate clash of style and subject. Instead of heroic landscapes or moralistic allegories, we have, well, what *are* we looking at here? Bureaucrats huddling? Dogs fighting? There's even the Tower of Babel seemingly used as a metaphor for, probably failed, attempts to cooperate. Curator: Precisely. Each small scene likely represents a specific element of the loan scheme or its consequences. The fighting dogs, for example, might symbolize the cutthroat competition for funds, while the Tower of Babel mocks the lofty but ultimately doomed goals of the policy. Remember, art of this era served to directly critique governance and administration, to a far larger public, due to mass media print productions. Editor: It makes me think about power dynamics. This artist is actively challenging those in power via popular imagery, deploying this very precise technique of engravings, that can be reproduced for the masses and widely disseminated. There is an intention here, a clear voice of dissent, which makes it even more impressive, knowing it comes from a rather distant past. Curator: Exactly. He harnesses artistic skill not for aesthetic beauty, but for political leverage. The image becomes a form of activism, an intervention into public discourse. It showcases how even historical artworks can shed light on power imbalances and ongoing debates about economic policy. Editor: Looking at it again with that in mind, the density almost becomes strategic. A visual representation of the layers of complexity inherent in governmental processes… or perhaps an intentional effort to overwhelm and disorient the viewer, just like bureaucracy often does. Curator: A potent observation. I leave now with a much enriched consideration on mass image production in nineteenth-century European politics. Thank you for this critical reading. Editor: And I'll take away the importance of digging beneath the surface, to really see art not as passive artifact, but active participant in the construction of reality, and deconstruction of its wrongs.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.