drawing, print, etching, engraving

#

drawing

# print

#

etching

#

11_renaissance

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Copyright: Public Domain

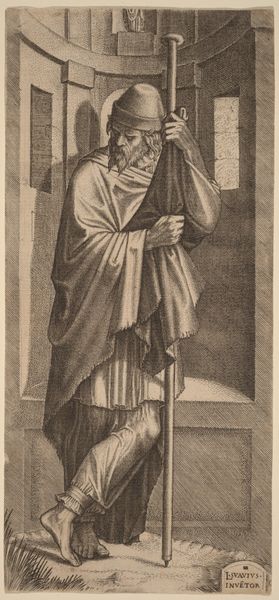

Editor: Here we have Lambert Suavius's engraving of St. Paul, made sometime between 1530 and 1576. The detail achieved in the folds of his robes, with just simple lines, is striking. How do you view the role of religious imagery like this in the Renaissance? Curator: Well, first, consider where the piece is today: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. A primary role for religious imagery shifted over time, from devotional object to artwork worthy of museum display. Images like this circulated widely, shaping perceptions and reinforcing power structures of the Church. How might this image of St. Paul function differently within a religious institution versus within the collection of an art museum? Editor: It feels like in a museum, the focus shifts to its artistic merits and historical context, potentially diminishing its spiritual impact. What can we infer about the public perception of St. Paul from this depiction? Curator: This is a key question. Notice the book, of course a symbol of knowledge, and his garb that references earlier Greco-Roman philosophers. By associating Paul with intellectual tradition, the image underscores the importance of the Catholic Church to the larger culture, in a society grappling with new philosophical, scientific, and religious viewpoints, like the burgeoning Protestant Reformation. The sword near his feet? Editor: Is it a literal representation, or a symbol of his martyrdom? Curator: Exactly! Think of it as a kind of warning. The composition subtly reinforces institutional power. Would you agree? Editor: I do. I never considered how an artwork's meaning evolves as its context changes over time, but it makes perfect sense. Curator: And that evolution is ongoing! The afterlife of an image is endlessly fascinating.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.