print, photography, site-specific, albumen-print

# print

#

landscape

#

outdoor photograph

#

outdoor photo

#

archive photography

#

outdoor photography

#

photography

#

site-specific

#

cityscape

#

albumen-print

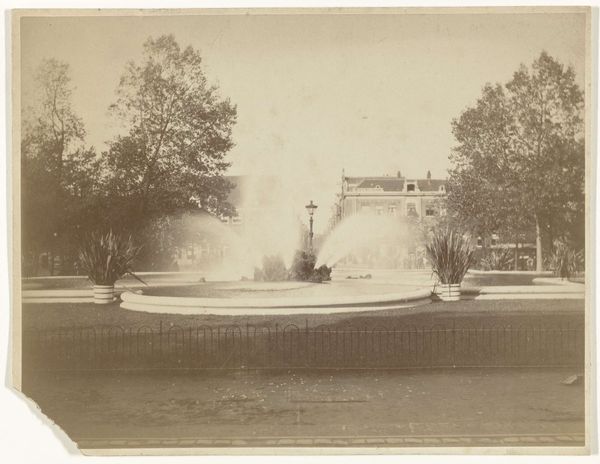

Dimensions: height 100 mm, width 148 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: James Valentine captured this remarkable albumen print titled "Crystal Palace bij Sydenham Hill," sometime between 1854 and 1880. Editor: It's certainly imposing. The Crystal Palace looms, but something about the subdued tones feels melancholic, as though it’s a ghost of a more vibrant past. Curator: Well, consider what the Crystal Palace represented. Built initially for the Great Exhibition of 1851, it symbolized industrial progress and Victorian ingenuity. An immense iron and glass structure meant to house the achievements of a nation. Valentine's albumen print captures the monument, removed and rebuilt in Sydenham. Editor: Yes, glass and iron— materials that, even in a photograph, speak to the ambitions of industrialisation. Look at the park layout as well, the ordered and controlled green space emphasizes this dominion. It’s a carefully constructed paradise. Curator: It certainly served as an archive for a nation eager to declare its cultural dominance. Think of the social engineering at play here. Consider, too, the labor required to manufacture the glass and iron, the labor to construct such an enormous building. Editor: But the building itself... those sweeping arches, the sheer transparency... It’s reaching for something beyond the industrial, isn't it? A kind of optimistic utopian vision. The symmetry throughout and glass facades really create an image that hints at idealized progress. Curator: Maybe, but I'm also thinking about what's not pictured. The pollution created by the industries supplying the materials, the urban overcrowding. What's also crucial here is understanding albumen as a binding agent— eggs were heavily traded globally from the mid-19th century onward, making practices like photography reliant on industrialized systems of agriculture and production. Editor: A shadow history in the materials themselves. Even so, the enduring visual symbol, especially considering the fire that destroyed the Palace later, becomes a memento mori of sorts, about grand designs. Curator: True, a physical symbol of what could be gained, but always with inherent, material constraints. I think, ultimately, we can use the print to question how such narratives about progress are created, sustained and visualized through images and things. Editor: It’s funny, isn't it? An attempt at permanence immortalized in a photograph now a relic, reminding us of time’s persistent march, despite even the grandest material achievements.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.