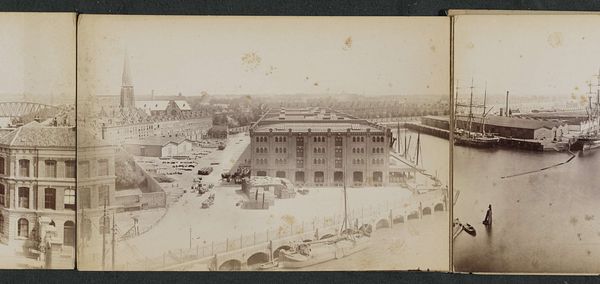

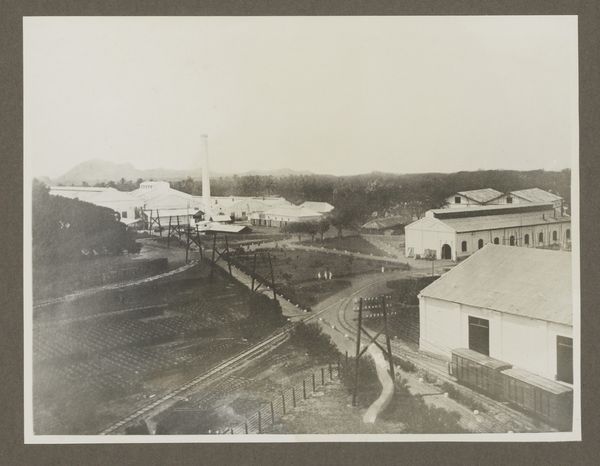

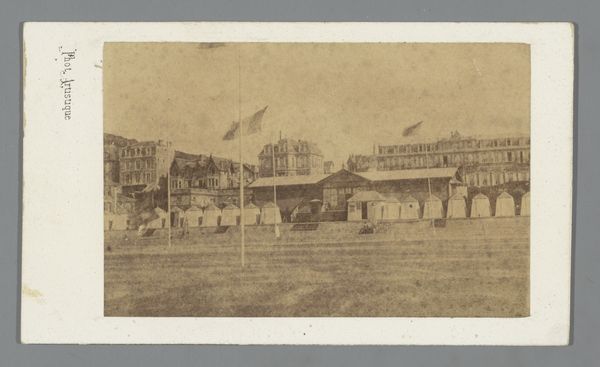

photography, albumen-print

#

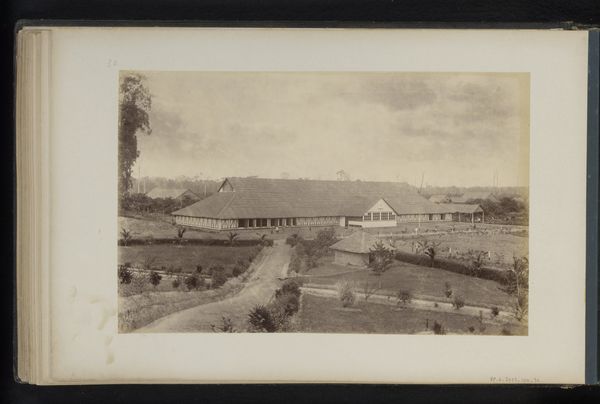

landscape

#

archive photography

#

photography

#

historical photography

#

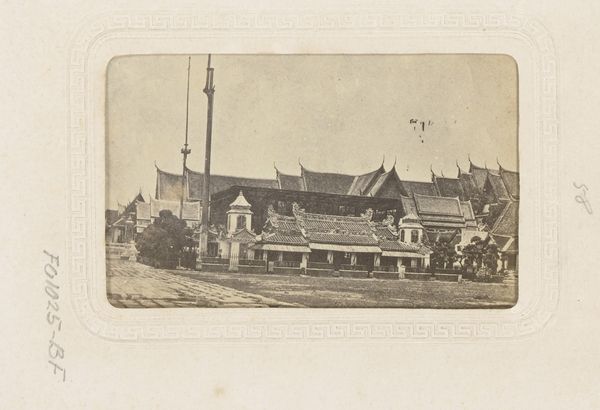

orientalism

#

cityscape

#

albumen-print

Dimensions: height 85 mm, height 52 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

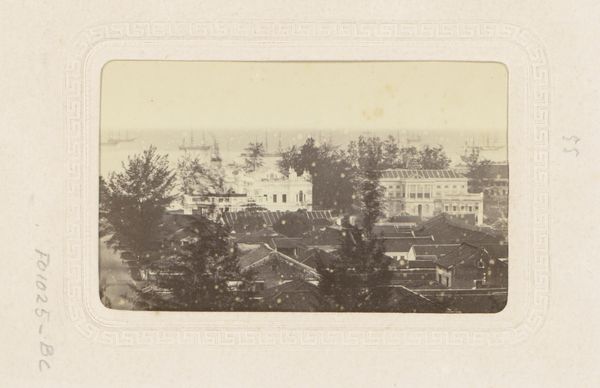

Curator: This is an albumen print titled “Gezicht op Singapore,” placing it somewhere between 1867 and 1880 and attributed to G.R. Lambert & Co. It resides here at the Rijksmuseum. What's your initial impression? Editor: There's a fascinating sense of stillness to this photograph, considering it depicts a bustling port city. The albumen print lends this sepia softness and almost palpable sense of age, but it is remarkable that we're able to witness the rapid growth of Singapore’s industrial networks. Curator: I think it does much more. Beyond industrial expansion, notice how the ships on the horizon almost mirror the architecture. I read them as symbolic of the reach of colonial power and its implications. The sea—always potent—is quite literally the support. Editor: But don't you think the physical qualities, being an albumen print, dictate so much of what we see? Albumen was favoured precisely because it captured such minute detail. So here we have the confluence of aesthetic preference alongside the colonial ambition to classify and control, both mediated through material process. Curator: I agree, it’s a striking visual archive, even evidence. To understand its emotional context, though, consider that photographic images like these were instrumental in constructing a visual vocabulary for European audiences. It allowed the West a kind of mastery, not simply through governing but by "knowing" its colonies intimately. Editor: Yet albumen printing required a significant amount of labour. Eggs were a key component. We often overlook the production of such photographs and its embedded colonial hierarchies; the labour it extracted from both humans and animals to satisfy colonial documentation needs. Curator: Absolutely. And by reading these photographs as aesthetic objects, we're both implicated in perpetuating these systems and also better equipped to challenge them. Editor: It certainly leaves you thinking about the weight of visual history and who is written into that history—and through which processes of material labour. Curator: Indeed. A silent document that speaks volumes.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.