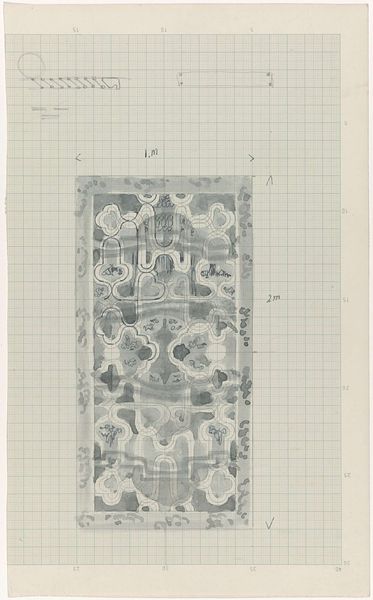

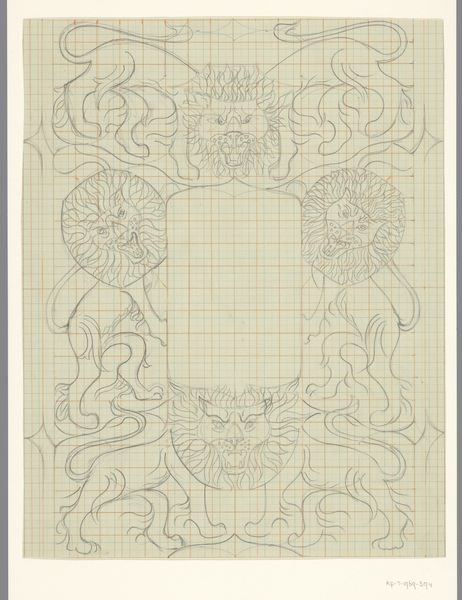

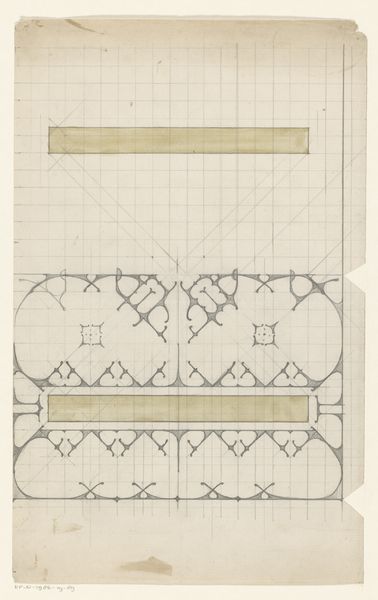

drawing, paper

#

drawing

#

art-nouveau

#

paper

#

geometric

#

architectural drawing

#

line

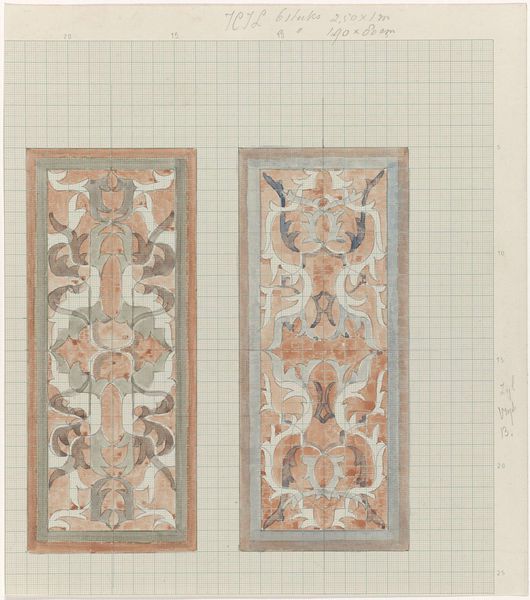

Dimensions: height 335 mm, width 156 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

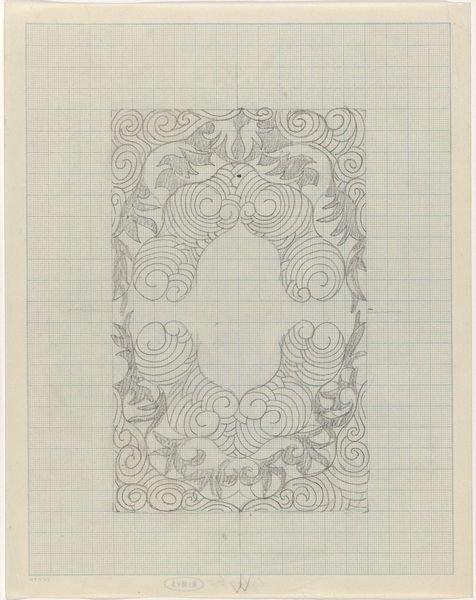

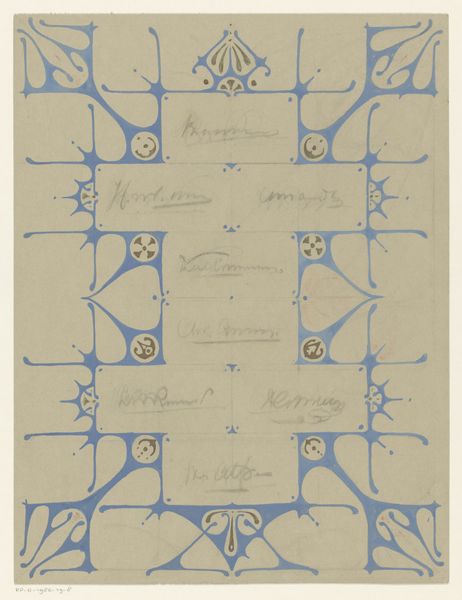

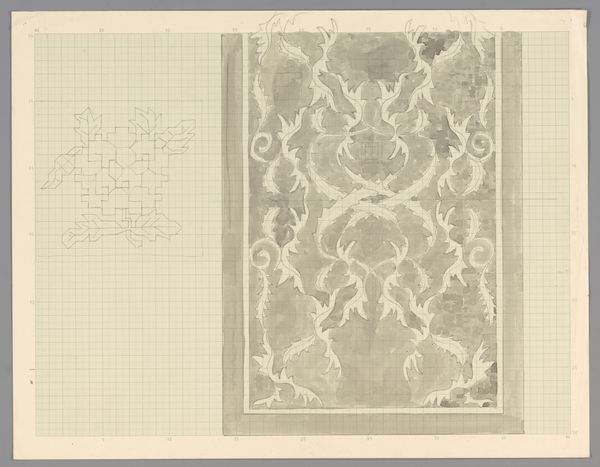

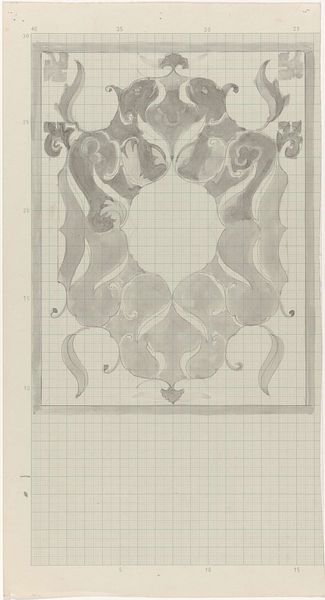

Curator: This "Decoratief ontwerp," a decorative design by Carel Adolph Lion Cachet, drawn sometime between 1874 and 1945 and currently held in the Rijksmuseum, feels...muted, almost shy. It's intricate, yet reserved. What strikes you first about it? Editor: My immediate thought goes to accessibility; the overlaid grid pattern evokes the legacy of standardized design, often employed to enable mass production, impacting many aspects of working-class and colonized people's daily lives in this period. The aesthetic, almost sterile, suggests that art is increasingly being designed not to stand on its own, but to function as part of a machine. Curator: Yes, that grid does ground it, doesn't it? But the Art Nouveau influences, those sweeping, organic curves fighting against the rigidity... there’s a tension, a little dance between freedom and control, maybe a reflection of the shifting social currents of its time. Do you agree that this piece hints to art-nouveau? Editor: Absolutely. Those curvaceous motifs pull from natural forms, attempting to soften the visual impact. It’s a strategic, or maybe even an insincere adoption, one of appropriating nature only for decorative purpose instead of highlighting humanity as intrinsically linked with it, you know? Almost co-opting natural forms. What does this design promote other than a lifestyle, an agenda accessible to so few? Curator: Maybe the aspiration was to bring beauty, or at least its aesthetic representation, into everyday life, to democratize good design for everybody's eyes regardless of its practicality. Is that possible, though? Editor: Possibly idealistic, given the era’s socio-economic divides, right? It becomes a sort of empty gesture, a beautiful surface masking systemic inequality. I mean, who could afford this stuff anyway, if translated into fabric, furniture, architectural designs...? Who were these designs really intended for, and at what cost to those excluded? Curator: And yet, the beauty persists! It whispers, "Look closer, question everything." I do wonder what Cachet had in mind. I think he meant good to all, but intentions may vary with its implementations. Editor: It’s in these tensions – beauty versus exclusion, nature versus industry, the ideal versus the real – that the drawing becomes powerful. Its visual appeal compels us to consider these complex layers, doesn't it? Curator: Definitely. This deceptively simple drawing is more like a quiet rebel, stirring the pot from within the gilded cage. Editor: A subversive seed, perhaps, planted in fertile, complicated ground.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.