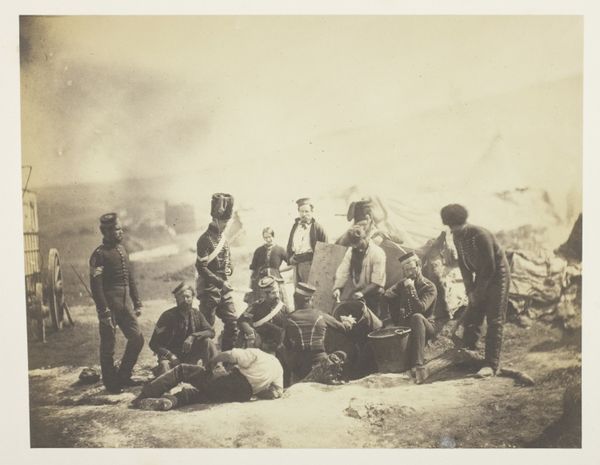

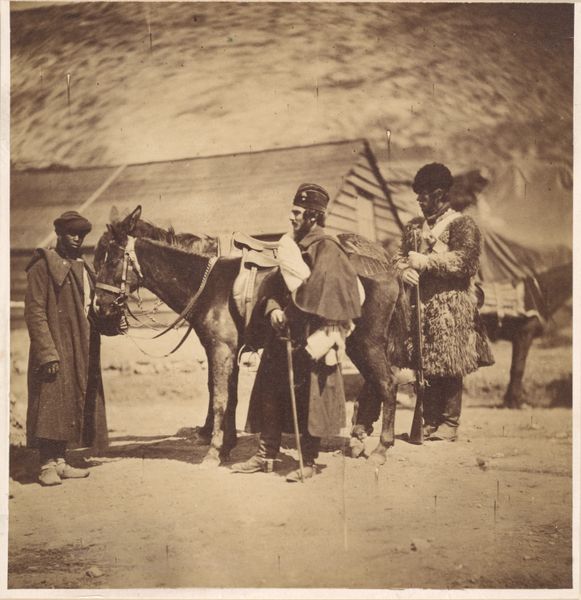

print, photography

#

print photography

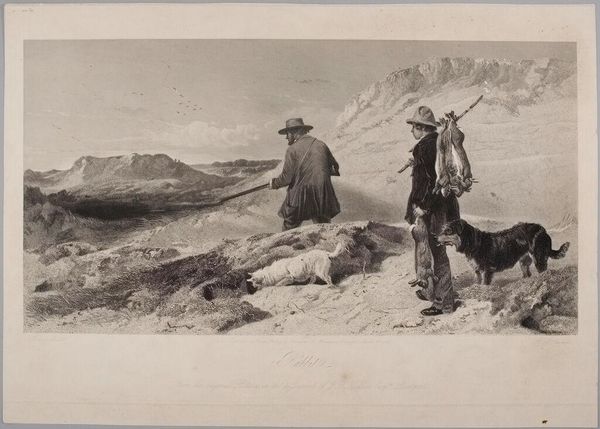

# print

#

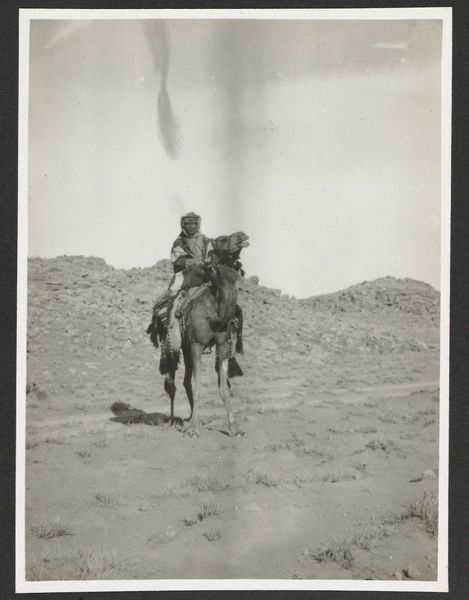

landscape

#

photography

#

indigenous-americas

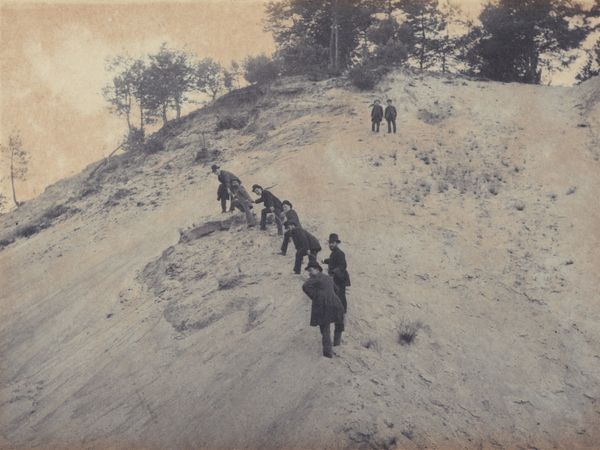

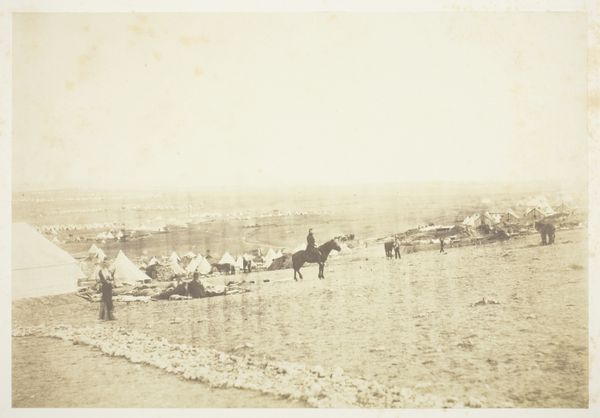

Dimensions: 26.5 × 37.5 cm (image/paper); 46 × 56.5 cm (mount)

Copyright: Public Domain

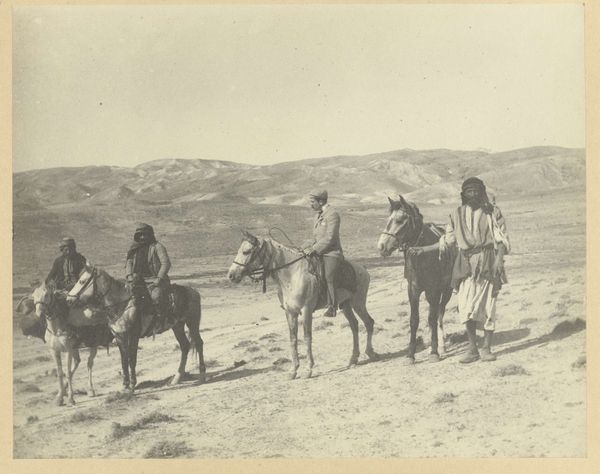

Editor: This is Edward S. Curtis's "Desert Rovers - Apache," a print photograph from 1903, held at the Art Institute of Chicago. The photograph portrays a group of Apache men on horseback, and the sepia tones give the scene a solemn and reflective quality. How do you interpret this work in terms of its historical and social context? Curator: The image appears as a straightforward portrait of a small group, but what Curtis presents us with is rife with the complicated and unethical power dynamics of representation. These images, while seemingly offering a glimpse into Native life, are deeply implicated in a history of colonial erasure. Curtis, like many photographers of his time, actively constructed an image of the “vanishing race,” furthering a narrative that justified dispossession and assimilation. Editor: So, what you are saying is, his work contributed to a narrative that disempowered the very people he photographed? Curator: Exactly. It’s crucial to understand that Curtis wasn’t simply documenting; he was participating in the construction of a particular, and damaging, narrative. Notice how the landscape, while physically present, seems almost secondary to the figures. This visual hierarchy mirrors the broader societal devaluation of Indigenous land rights and sovereignty. What do you make of their expressions and attire? Do you feel they offer a window into individual agency, or do they seem mediated by Curtis’s vision? Editor: It's difficult to say. There is a stoicism to their posture and dress that seems intended to convey a particular kind of "native" identity, now that you mention it, seemingly crafted for an outside viewer rather than being entirely self-determined. This makes the photo less of a representation and more of a statement on the colonizers part, one could say. Curator: Precisely. Recognizing Curtis's photographs as constructed narratives is crucial to engaging with them critically. We should ask ourselves: Whose story are we really seeing? And how can we be more attentive to the voices and perspectives that have been historically marginalized and even actively silenced? Editor: I’m beginning to understand how much the social context impacts how we view this photograph, making us more critical towards historical narratives and colonial representations. Curator: Indeed. This kind of questioning of the visual record can equip us to become more thoughtful consumers and critics of visual information overall.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.