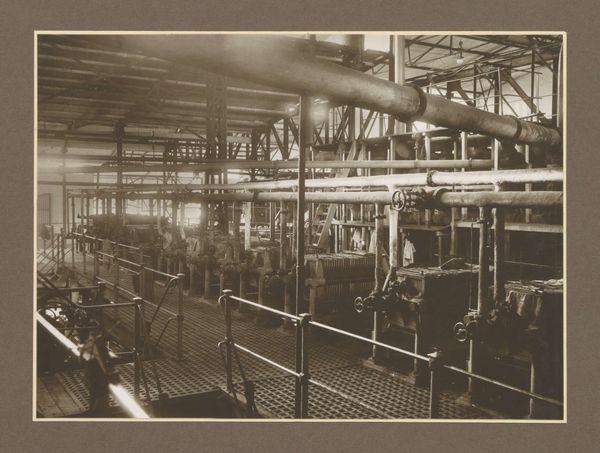

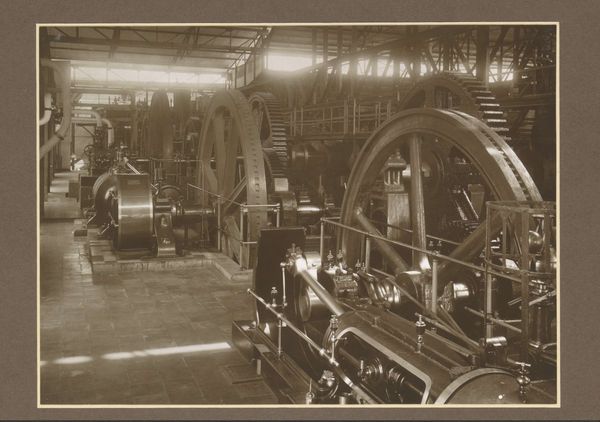

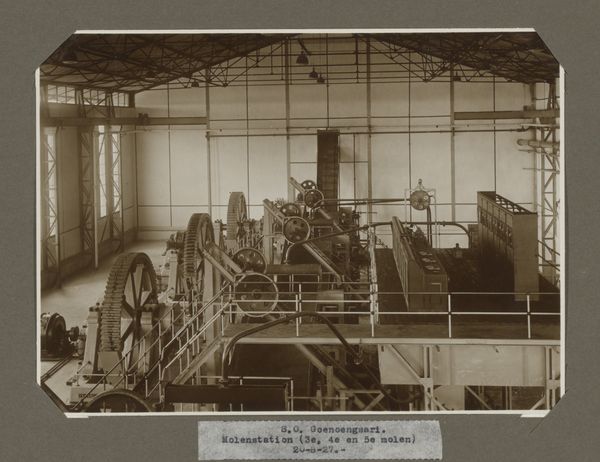

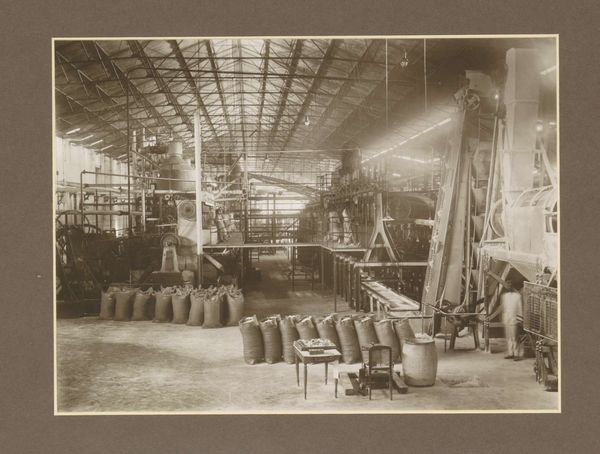

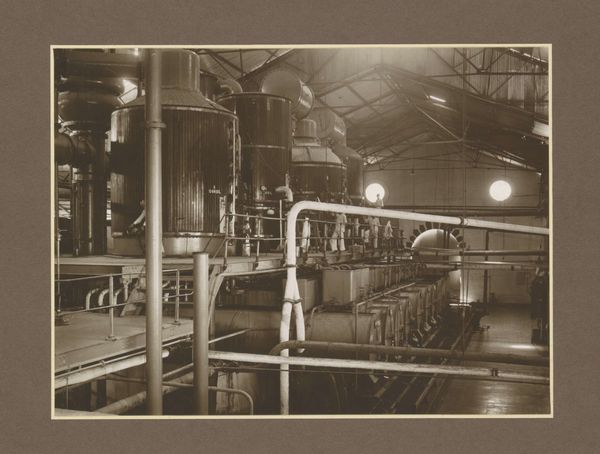

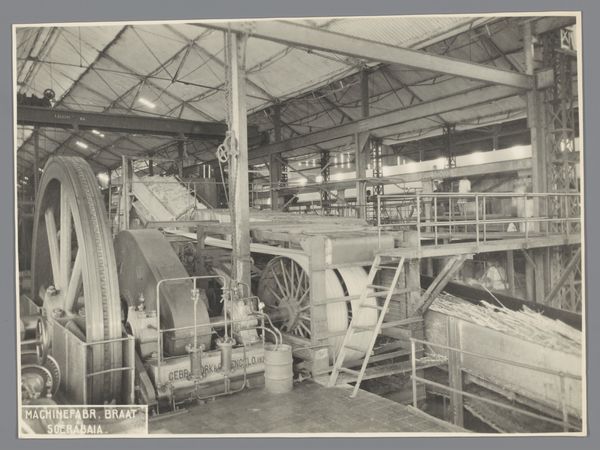

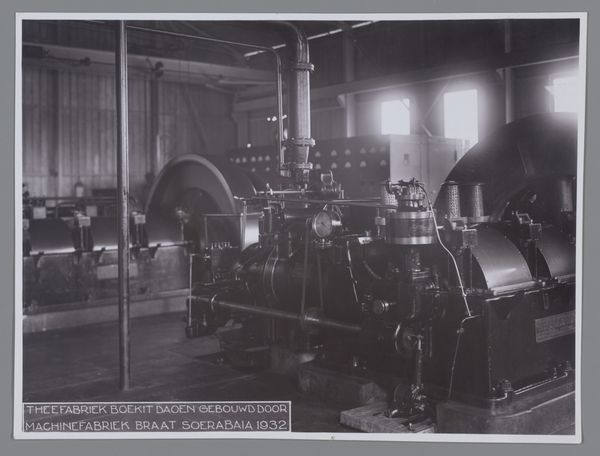

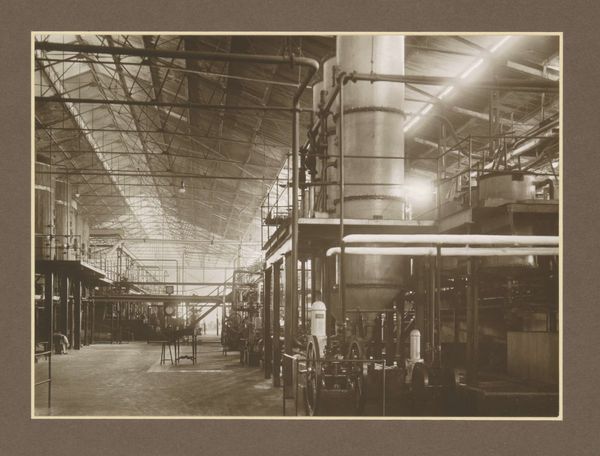

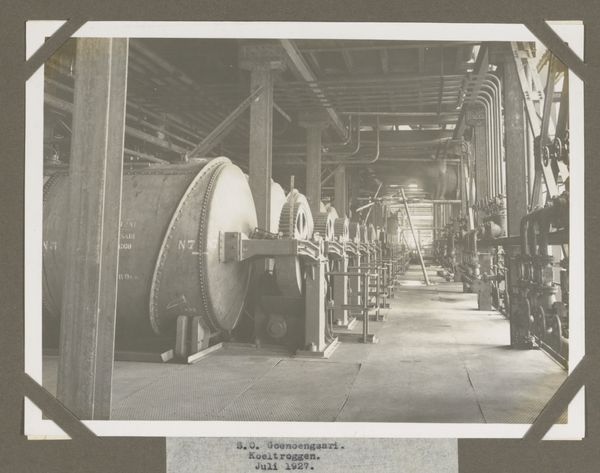

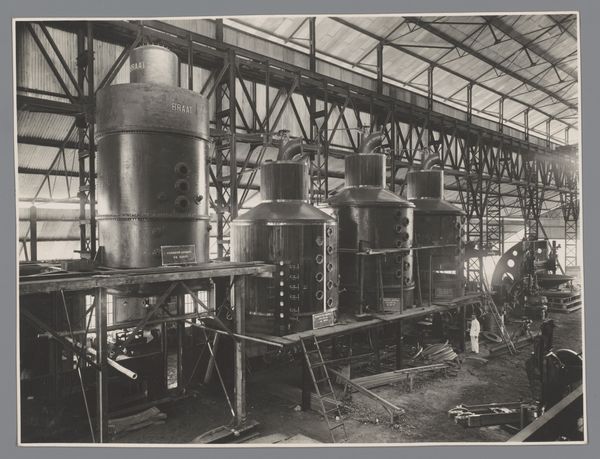

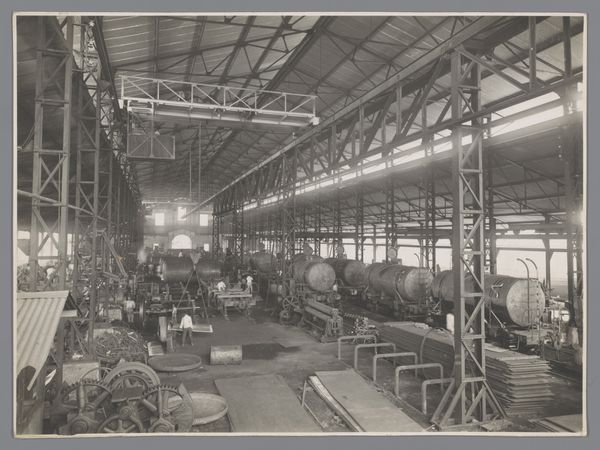

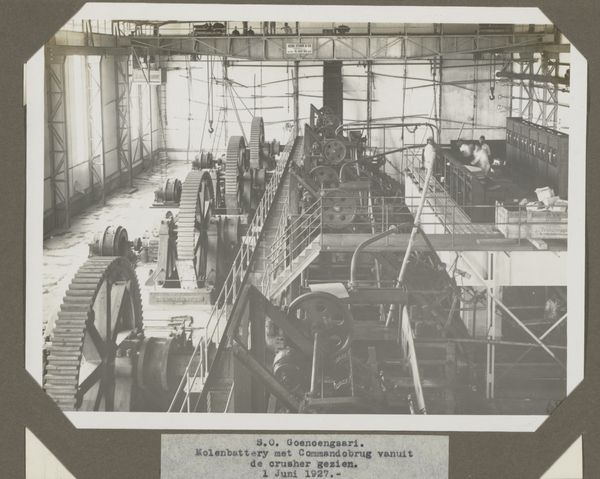

Machines en werknemers in een hal van suikerfabriek Goedo te Djombang op Java c. 1925 - 1930

0:00

0:00

photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

portrait

#

landscape

#

archive photography

#

photography

#

historical photography

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

modernism

Dimensions: height 297 mm, width 450 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: We're looking at an image attributed to Isken, titled "Machines and workers in a hall of sugar factory Goedo to Djombang in Java," likely taken between 1925 and 1930. It's a gelatin silver print, a medium commonly used for photographic documentation at the time. Editor: My initial reaction is the sheer scale—the machinery is imposing. And then there are these small figures almost lost in the industrial landscape. There's a real feeling of dehumanization. Curator: Exactly. This photograph comes from a period of intense industrialization in colonial Indonesia. Sugar plantations were a crucial part of the Dutch economy, so images like this were meant to showcase progress and productivity. Editor: But looking closer, the so-called "progress" came at a cost, didn't it? The workers, mostly local Javanese, are operating dangerous machines under harsh conditions for very little pay. It's a stark illustration of colonial labor practices. Curator: Indeed. And this image performs a kind of erasure. While seemingly presenting a factual depiction of the sugar factory, it obscures the realities of power dynamics. The emphasis is on the machines, while the human element becomes secondary. Editor: It feels staged, doesn't it? These workers, possibly positioned for the photographer. Their presence feels tokenistic, like visual confirmation of activity, but ultimately emphasizing the industrial spectacle. What are they thinking and feeling? Their experiences seem entirely overlooked. Curator: Precisely. What isn't shown in such photographs reveals just as much about colonial viewpoints as what *is* present. It embodies that power imbalance by centering industrial might. Editor: It leaves me wondering, too, about the photographer's own role. Did they see themselves as simply documenting industry, or were they complicit in visually normalizing this exploitative system? How does photography contribute to the perpetuation of colonial ideology? Curator: Excellent question. By examining not just the photograph, but also its social context, we can confront these challenging histories and power dynamics. Editor: Yes, thinking critically about images like this helps us to examine our present. Whose stories get told, and whose get ignored, becomes more evident with each viewing. The role of these images needs unpacking continuously.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.