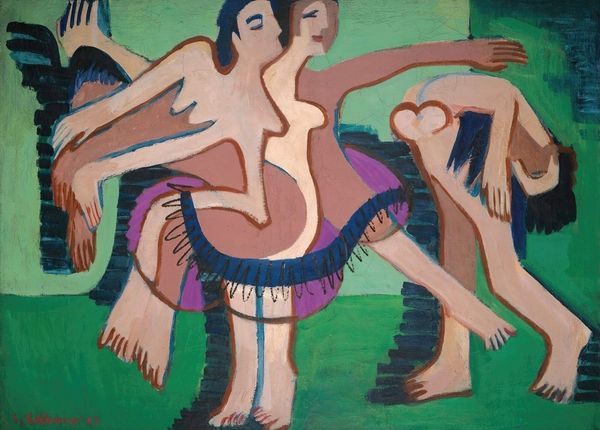

painting, oil-paint

#

painting

#

oil-paint

#

figuration

#

oil painting

#

group-portraits

#

expressionism

#

naive art

#

nude

Copyright: Public domain

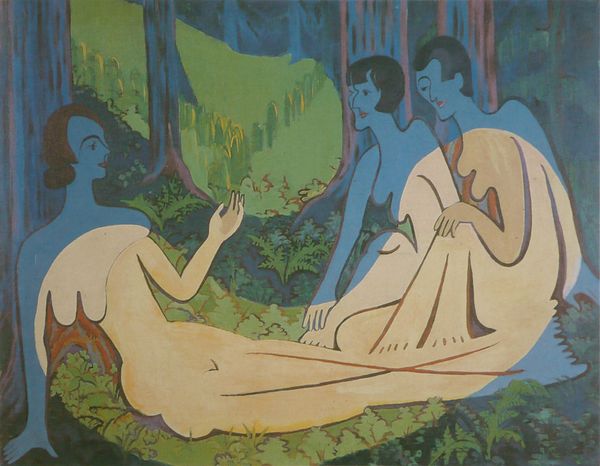

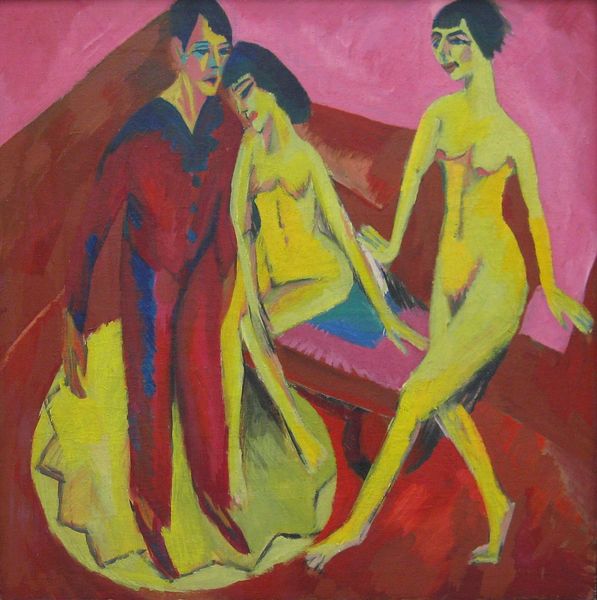

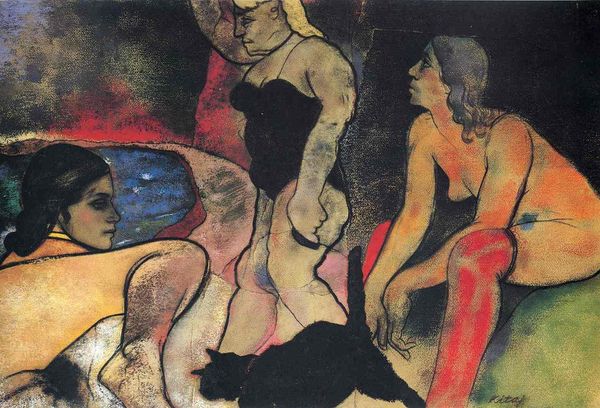

Curator: So, we're looking at Harry Phelan Gibb’s "Three Graces," an oil painting created in 1911. It’s quite striking, isn't it? Editor: It is! My first thought is one of unease, perhaps even otherworldliness. The colors are peculiar and the composition somewhat naive, or deliberately raw. What's going on historically, in 1911, with imagery like this? Curator: Well, expressionism was gaining traction, and artists were exploring subjectivity and emotion in bold ways, so it certainly falls into that broad category. However, it's also important to remember that this period was one of profound social change, so the depiction of the female nude, which can be located in historical references, reflects on themes of sexuality, social anxieties and gender roles, even subversion in imagery. Editor: Absolutely. And, thinking about materials, look at how thinly Gibb has applied the oil paint – almost like tempera in places. It denies the smooth, fleshy quality often associated with nudes. Is this, then, about pushing back on classical notions of beauty and sensuality through material exploration? The raw texture amplifies that slightly unsettling effect, and perhaps directs the view beyond the literal rendering. Curator: A fair point. Consider too how the artist’s process democratizes painting by exploring texture with this limited palette to present figuration. This resonates with broader anxieties in culture: is the definition of fine art broadening by incorporating naive, crude representation, to be determined or dismissed? Are artistic institutions welcoming of new, accessible visions? Editor: These are clearly not idealized bodies. The figures appear almost androgynous. In that, do the androgynous representation offer to question established and hierarchical forms of presenting genders in portraiture? There appears almost like an artful innocence at work here. Curator: You see that at work, perhaps in those cool tones or the seemingly child-like details in the wallpaper, but it’s hard to definitively declare an intentional disruption. Looking back to materiality, however, Gibb really foregrounds the paint itself as something tangible and present, rather than a vehicle for illusion. And considering its display context, where would it have lived? Was it for the gallery scene, private collections or did it occupy an uncertain status as “high” or “low” art? Editor: These questions reveal much of the history that lives in such a peculiar composition, pushing boundaries both of the definition of painting as an activity but the very context within which we engage in “Art” itself. It will certainly keep us occupied with interesting dialogue. Curator: Indeed. The painting demands more than a passing glance, which should certainly prompt much wider conversations than we have time to have here today.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.