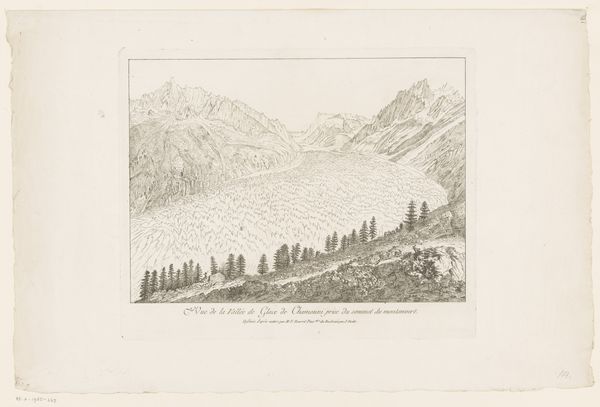

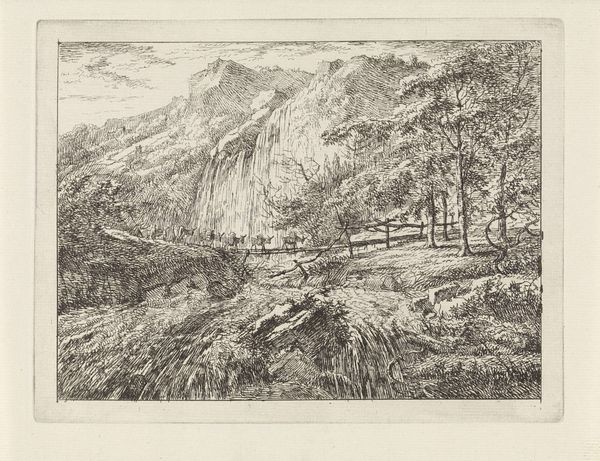

Dimensions: height 266 mm, width 321 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

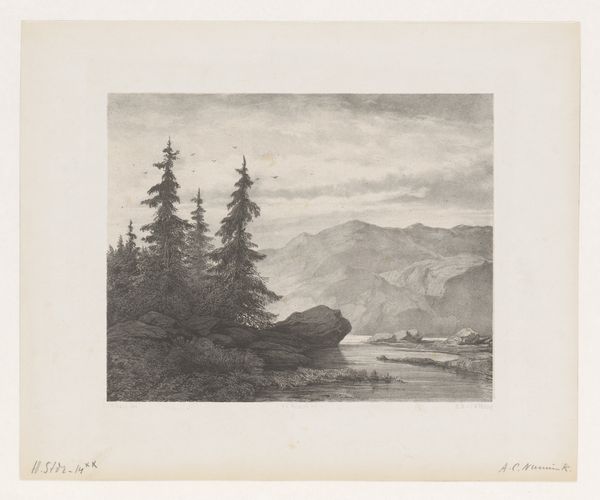

Editor: Here we have Angélique Moitte’s "Gezicht op de Mont Blanc," made between 1749 and 1799, using pencil. It's a pretty scene, but feels so… controlled. Almost sterile. What do you see in this piece? Curator: The precision is key. While seemingly a simple landscape, it's a loaded depiction tied to larger dialogues of power and representation. This wasn’t just about capturing natural beauty. Ask yourself, who had access to these landscapes, and who had the power to represent them? Editor: So, the act of depiction is itself a statement? Curator: Absolutely. Landscape imagery, especially during this period, served as a way for the elite to assert their dominance, a sort of visual claiming of territory, mirroring colonial expansion and the subjugation of nature. Consider how the ‘picturesque’ aesthetic often flattened diverse ecological realities into a homogenous ideal. Editor: I see. So it's not just a drawing of a mountain; it’s connected to social hierarchies? Curator: Precisely. The supposed 'neutrality' of landscape often masks the socio-political realities embedded within it. The absence of laboring figures in the foreground further reinforces this idea. Whose story is being told, and whose is being erased? Editor: That gives me a lot to think about regarding landscape art. It’s never just about the view. Curator: Indeed. By interrogating the power dynamics at play in its creation and reception, we can move beyond a passive appreciation of aesthetics. I wonder, does this change how you now look at landscape art? Editor: Absolutely. I see the landscape now as being embedded in human interactions and politics. I’m going to research more about the role of women artists in that time period.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.