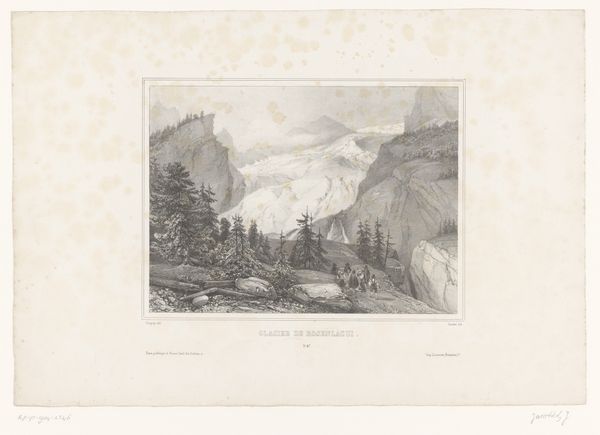

Dimensions: height 245 mm, width 365 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

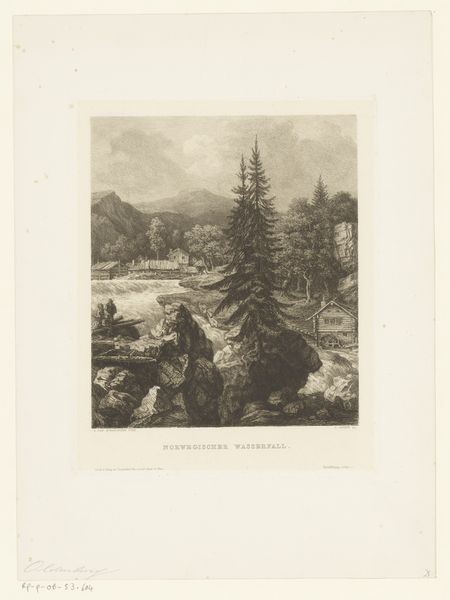

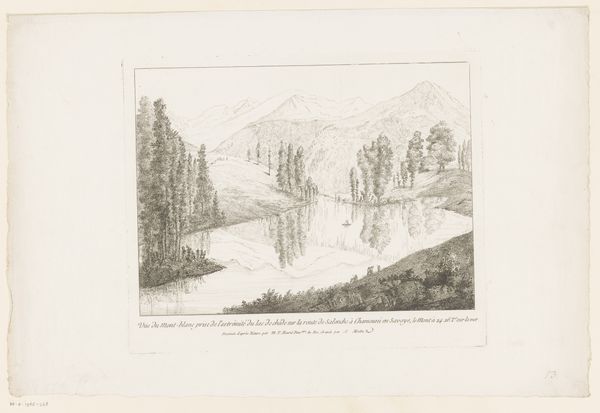

Curator: Here we have Louis Joseph Masquelier's "View of the Lower Grindelwald Glacier," created sometime between 1751 and 1811. It's an etching, meticulously crafted through the intaglio process. Editor: The grayscale immediately sets a solemn, almost haunting mood. It's an impressive display of tonal range, given the limitations of the medium. The composition draws my eye upward, toward those towering pines and the glacial vista. Curator: The picturesque style, a precursor to Romanticism, is very much at play here. Note how Masquelier uses the foreground figures and the rustic fence to frame the overwhelming grandeur of the natural landscape. The artist's rendering implies a sublime contrast between human scale and the infinite space, a common trait of the movement's emphasis on subjective emotional responses to nature. Editor: It's interesting how the artist uses line work to distinguish between the textures: dense, almost chaotic hatching to evoke the foliage versus the more regular patterns used for the cloudy sky and the distant mountain ranges. What do you make of the small human figures down in the left corner? Are they intended to be allegorical, or just… present? Curator: The human element in landscape depictions during this era often functioned as a means to establish perspective. They could also symbolize humankind's place within or alongside nature, perhaps an aspiration toward harmonious coexistence, depending on the setting and artist's philosophy. This ties into the broader 18th-century fascination with pastoral scenes and idealized natural settings. Editor: Still, those distant icy peaks – so coolly rendered. Even as someone who favors the abstract, the detail given to light and shadow really makes an impact. How do we situate such landscape imagery in an era of intense political upheaval and revolution? Curator: Precisely. That socio-political dimension provides crucial context. The artistic choice to focus on unspoiled, immutable natural landscapes also speaks to contemporary social unrest and fleeting revolutionary fervor, an escape into an imagined simpler past. Editor: Masquelier truly captures that interplay between observation, ideology, and emotional expression inherent in 18th-century art and the birth of landscape painting. Curator: Indeed, viewing this print allows one to trace both formal evolutions within visual art and broader developments throughout 18th century social constructs.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.