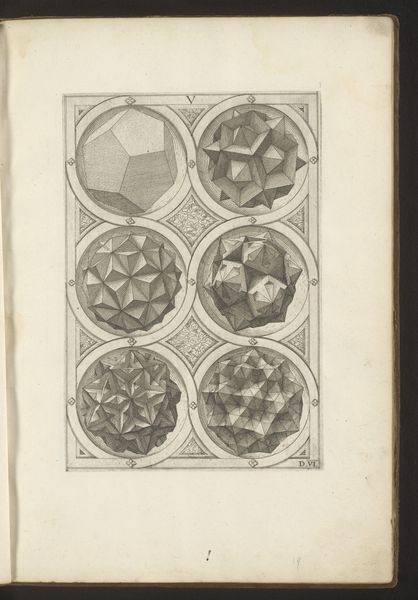

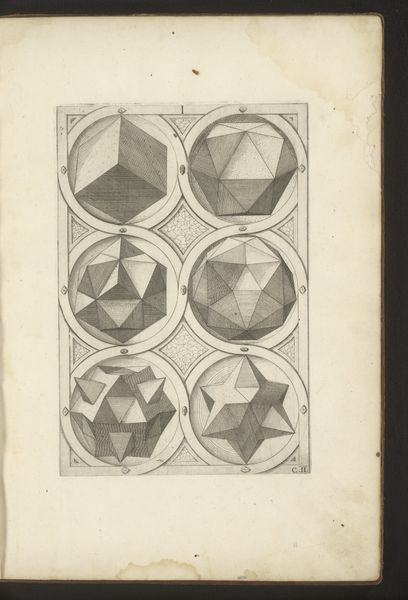

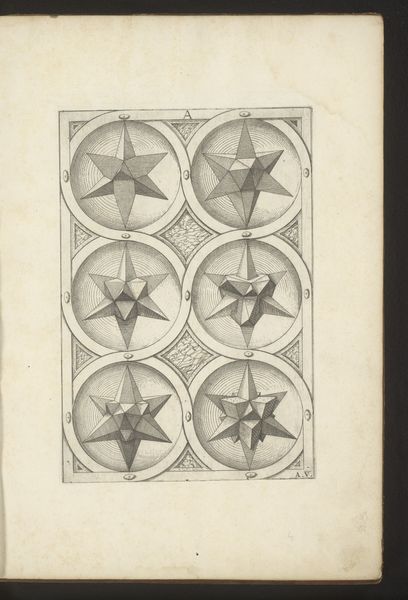

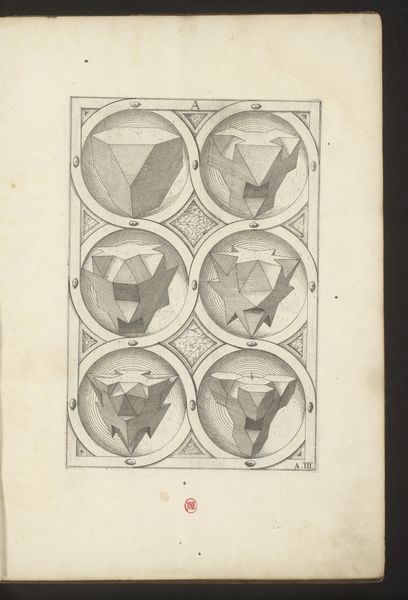

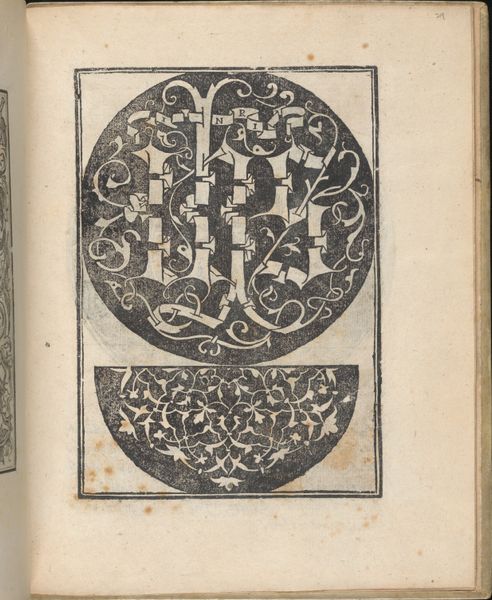

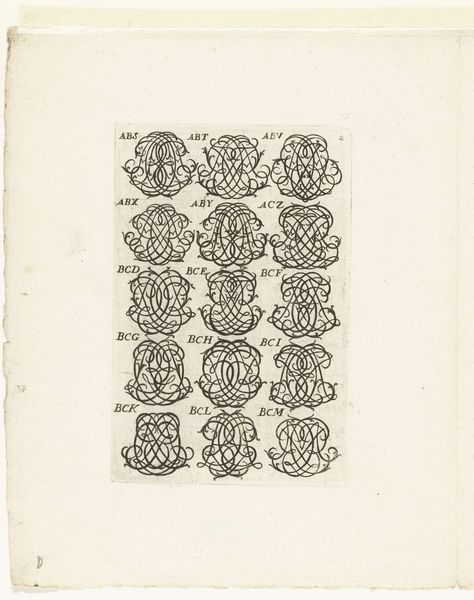

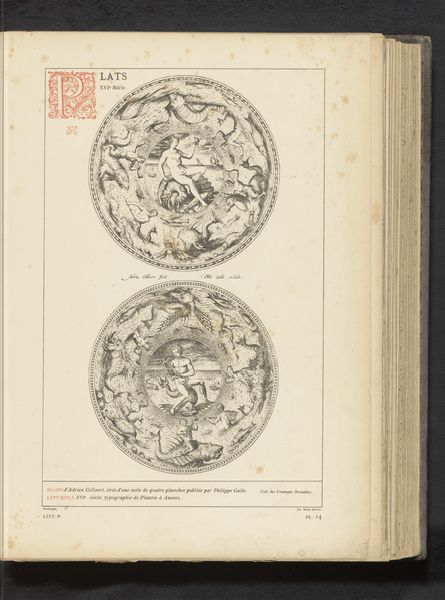

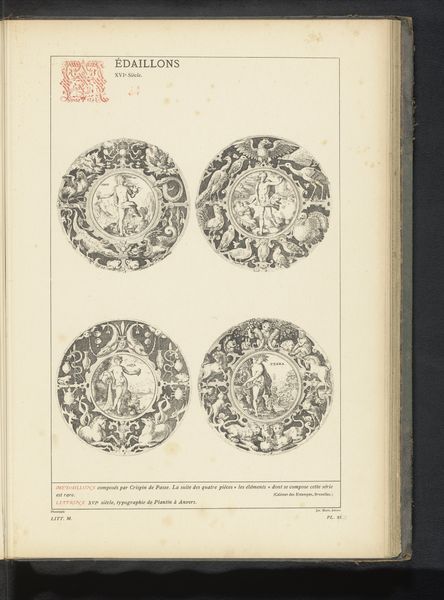

print, engraving

#

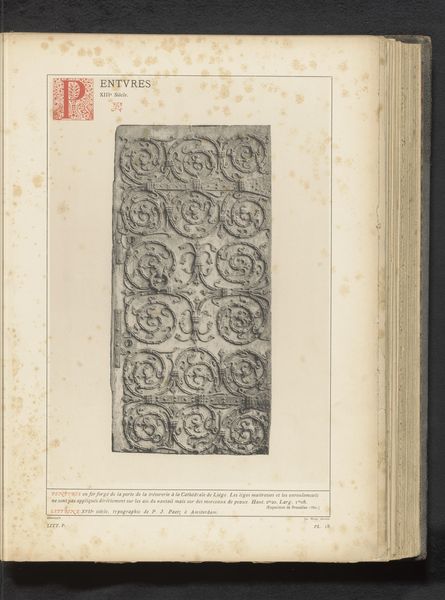

aged paper

#

toned paper

#

ink paper printed

# print

#

old engraving style

#

11_renaissance

#

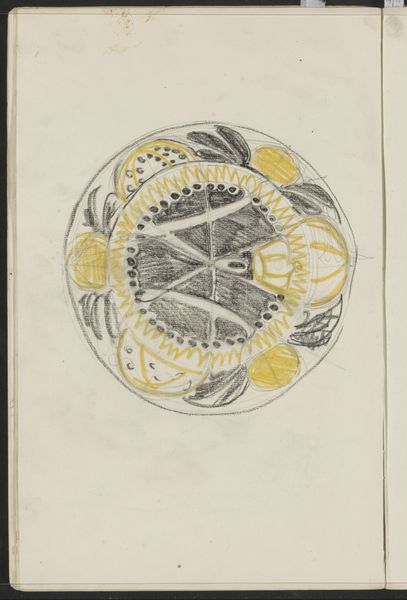

personal sketchbook

#

geometric

#

pen-ink sketch

#

ink colored

#

pen work

#

sketchbook drawing

#

northern-renaissance

#

sketchbook art

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 256 mm, width 176 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Looking at this engraving from 1568 by Jost Amman, titled "Six Polyhedra Based on an Icosahedron," now residing in the Rijksmuseum, I immediately feel transported to a world of Renaissance intellectual exploration. Editor: My initial impression is how deceptively simple it looks. At first glance, it's just geometrical shapes, but the meticulous detail suggests something more, perhaps a striving for order in a world increasingly seen as chaotic. Curator: Precisely! These polyhedra weren't just decorative. Geometry, during the Renaissance, was considered the key to understanding the universe. The icosahedron, a 20-sided polyhedron, was particularly fascinating, seen as representing the element of water. Amman's variations on this form demonstrate an engagement with mathematical and philosophical concepts prevalent at the time. We're not merely viewing art; we're encountering an encoded worldview. Editor: And, thinking about that encoded worldview, who was this knowledge available to? It strikes me that such precise geometrical forms, and the education needed to understand their symbolic value, were largely confined to elite circles. Were these images designed to communicate meaning, or to reinforce existing social hierarchies by creating exclusive intellectual domains? Curator: That's a vital question. Certainly, the Renaissance saw the rise of artistic patronage where knowledge and art intertwined within elite circles, and the use of geometry had cultural weight that carried emotional resonance over time. This could suggest a desire for both intellectual exploration and a confirmation of social status through these artistic endeavors. Editor: The act of engraving itself interests me. This reproduction, rather than a unique creation, also says something about knowledge production during this period: it invites widespread dissemination and creates space for wider reception among intellectual elites. It makes one think about networks of humanist scholars circulating and exchanging such prints with one another. Curator: Thinking about networks feels accurate here. There's something timeless about Amman's shapes; these polyhedra resonate even now, representing our ongoing effort to impose order, or at least understanding, on complexity. Editor: Exactly. Looking closely, these shapes and subtle tonalities also inspire consideration of the connection between art and power. By presenting the seemingly "objective" knowledge of geometry in artistic form, these types of artworks legitimize this knowledge while visually constructing power dynamics between the informed and the uninformed. Curator: Considering the cultural and symbolic meanings inherent in images, from sacred icons to geometric forms, remains key to their interpretation—past and present. Thank you for this insightful discussion! Editor: And thank you for pointing out the symbolic context within geometry. It offers insight into understanding this era, while still informing our own visual vocabularies today.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.