drawing, paper, pencil

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

paper

#

pencil

#

orientalism

Dimensions: height 435 mm, width 267 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

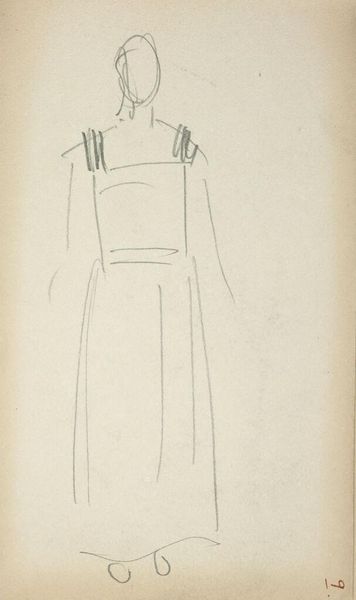

Curator: At first glance, there's a haunting quality about this piece, "Clothing of a Dignitary from the Dutch East Indies," sketched between 1865 and 1936 by Nicolaas van der Waay. The subject's facelessness only amplifies this impression, as if we're encountering a ghost of colonial history. Editor: I am drawn to how deliberately van der Waay depicted this outfit; so much intricate detail, from the cut of the jacket to the folds in the skirt. What can we learn about textile production from such a representation? Curator: That's a very material point. Looking closer, notice the weight of all that hardware on the dignitary's chest. It appears almost theatrical—or even tragic. Does the very fabric of the garments betray a hidden history of colonial commerce and control? Editor: Absolutely, all those fine decorations involved craftspeople, specific weaving traditions... and ultimately economic structures dependent on power and perhaps exploitation. The sheen and status projected undoubtedly masked other harsh realities, I suspect. Curator: And this leads me to consider what the paper and pencils signify as tools in recording and representing this image. Think of the role sketching played in exploration, surveying, even dominance during this era. The sketch, the material trace, captures that complicated exchange between observer and observed. Editor: Exactly! And it's not just *what* is depicted, but the medium itself—pencil on paper—which reveals colonial processes: the means of recording, documenting, appropriating, even claiming the visual world, making exotic cultures legible and consumable. Curator: You’re right to point that out, and that the style – clearly Orientalist – furthers this consumption through representation. Even in its seeming incompleteness, this sketch echoes of longing, lost empire, maybe regret. Who exactly commissioned or consumed images like this, and what desires or anxieties were at play? Editor: Precisely! Think about it: Who had access to create art like this? Who could consume these kinds of images in that time? Art and material are bound, each defining and shaping the other through colonial processes. Curator: Reflecting on our conversation, it strikes me that such understated pieces – with only pencil and paper – speak volumes on complicated human experiences and, of course, histories. Editor: I agree. By foregrounding material practices and social context, we can shed new light on what is pictured here.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.