painting, public-art, fresco, mural

#

public art

#

allegories

#

allegory

#

painting

#

street view

#

public-art

#

figuration

#

fresco

#

abstraction

#

mexican-muralism

#

history-painting

#

mural

Copyright: Public domain

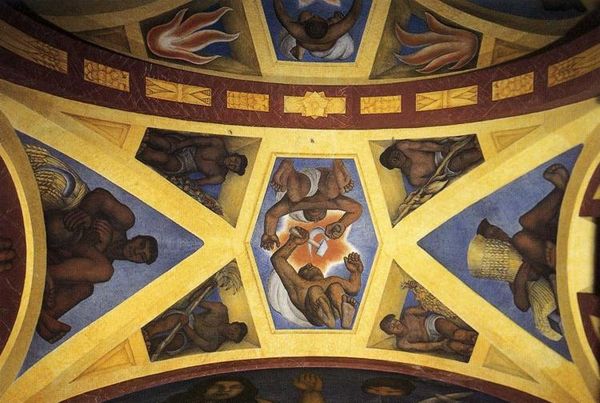

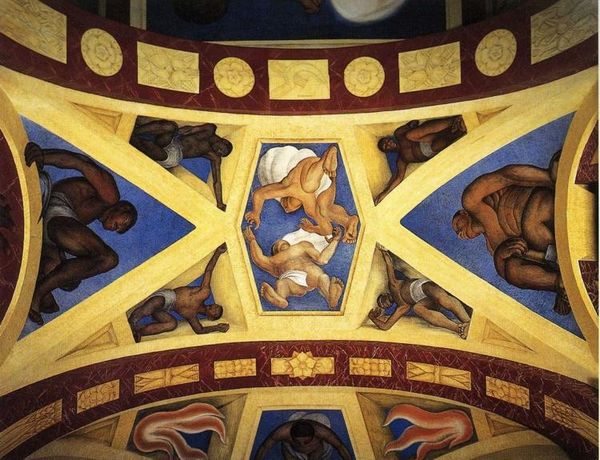

Curator: Looking up at Orozco's "Man of Fire," completed in 1939, the scale and energy of the fresco are immediately striking. The fiery reds and oranges dominating the central figure seem almost to writhe above us. Editor: It's overwhelming, almost apocalyptic. The figures around the edges, rendered in monochrome, seem to be either succumbing to or enabling the chaos at the center. What's the fresco medium itself communicating about labor in Mexico at this moment? Curator: The fresco technique—pigment applied directly to wet plaster—is inherently public, a deliberate and laborious process integrating the artwork into the very architecture, making it inextricably tied to the building's history and function. Editor: Exactly, and the placement of this mural within the Hospicio Cabañas speaks volumes about Orozco's sociopolitical aims. He uses the imagery of destruction and renewal to question established power structures and imagine radical futures. Consider that he depicts a figure consumed by flames—an allusion to sacrifice and transformation, which powerfully questions how power exploits vulnerability. Curator: And let’s consider the means to produce monumental, site-specific frescoes: scaffolding, preparation of walls, grinding pigments. The very act of producing the work demanded collective labor in Guadalajara at the time. We must ask, who was participating, and under what conditions? Editor: The skeletal figure dominating the fresco acts as both perpetrator and victim. I'm wondering about its context of nationalism following the revolution; is Orozco critiquing state-sponsored violence? Or perhaps he's grappling with industrialization that further endangered populations deemed less valuable? Curator: Right, so the allegorical implications invite ongoing exploration around who gets destroyed in periods of economic crisis. Perhaps the cyclical and ever-present quality is why it retains its urgent contemporary message. Editor: Orozco definitely forces us to engage with discomfort—not just in his unflinching representation of destruction, but in the very positioning of power and its potential for cruelty. His ability to question that from above is provocative and critical for interpreting narratives of Mexican progress at this time. Curator: Precisely. It asks, what, materially and ethically, is gained from such historical trajectories. It forces us to look closely at who labors, what survives—and at what expense.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.