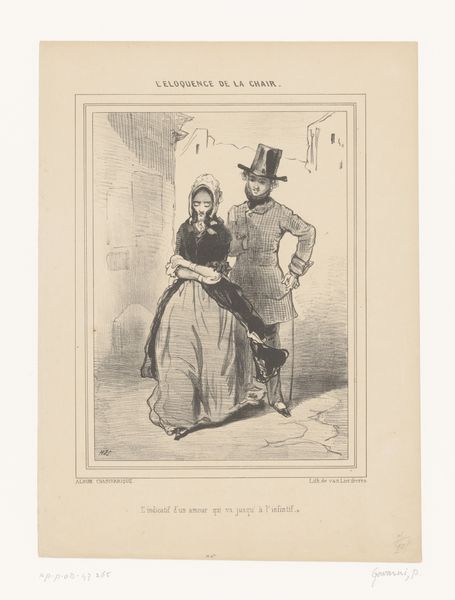

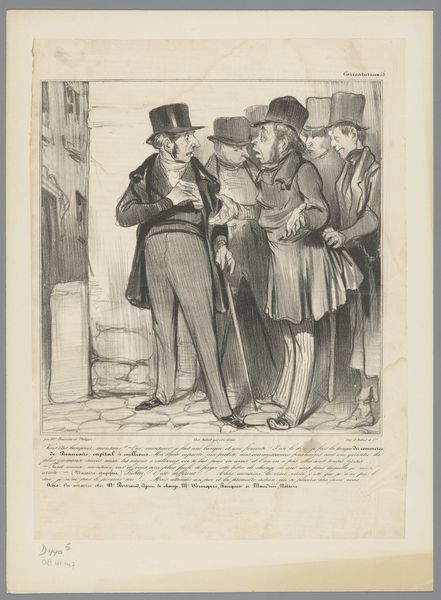

The Turnstile. A new machine invented by the enemy of crinoline petticoats, plate 15 from L'exposition Universelle 1855

0:00

0:00

Dimensions: 199 × 228 mm (image); 279 × 362 mm (sheet)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: This is "The Turnstile," a lithograph created in 1855 by Honoré Daumier. It’s a piece intended for the "L’Exposition Universelle" series. Editor: Immediately, I’m struck by the starkness of the black and white and the raw quality of the lines. The machine itself appears crude, almost menacing, given the clear distress of the woman being processed by it. Curator: Yes, Daumier frequently used caricature to critique society. The "new machine invented by the enemy of crinoline petticoats," as the caption reads, skewers the prevailing fashion. These voluminous skirts were quite the status symbol. Editor: Right. And the material excess of the crinoline becomes the object of social commentary through the lithographic process. He's using the readily available medium of printmaking to spread his message to a wider audience. It is so accessible. I imagine this was printed on fairly cheap paper. Curator: Exactly! And beneath the surface, the turnstile symbolizes the mechanization and objectification of women, forcing them through this device in the name of fashion and social expectation. We can imagine it as an oppressive technology shaping the female form to fit an ideal. The reactions on their faces are worth a deeper look. Editor: Absolutely. Looking closely, you notice the rather indifferent functionary to the side, mechanically processing women. The entire scene becomes this conveyor belt, quite literally pushing these bodies toward…what, uniformity? Conformity? Curator: The figures in the background observe passively, hinting at society’s complicity in upholding these standards. There is a sense of social satire inherent within Daumier's commentary on vanity, progress, and even alienation in a modernizing world. The fear of technology imposing itself upon traditional values rings so true here. Editor: Considering the means of production - the relatively accessible lithograph - heightens the message. This wasn't an exclusive oil painting for the elite; it was a reproducible image designed for mass consumption, directly critiquing mass consumerism! It all flows together. Curator: It serves as a fascinating mirror reflecting anxieties about industrial progress and its effects on gender, class, and individual liberty. Editor: For me, this piece is more than just satire; it’s a study in the human cost of fashion, technology, and progress itself, brought to us via an extremely insightful use of readily available, and affordable materials.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.