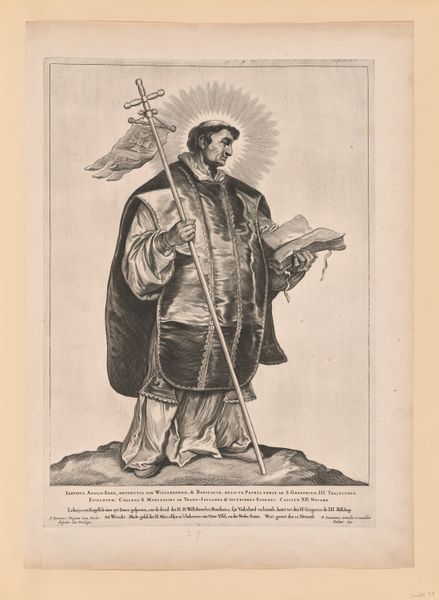

Saint Werenfridus, from Saints of the North and South Netherlands 1650

0:00

0:00

drawing, print, paper, engraving

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

baroque

# print

#

paper

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: 445 × 315 mm (image/plate); 515 × 380 mm (sheet)

Copyright: Public Domain

Editor: This is Cornelis Visscher’s "Saint Werenfridus, from Saints of the North and South Netherlands," made in 1650. It’s an engraving on paper, so a print. The detail in the robe is incredible, and the halo gives the figure an ethereal feel. What can you tell me about this work, thinking about how it was made and why? Curator: Well, consider the production of prints like this in the 17th century. Engraving wasn't just a skill; it was a complex process involving specialized tools and a deep understanding of materials. Think about the labor involved in creating these intricate lines, transferring images, and the role these prints played in disseminating religious and historical narratives. What impact might the accessibility of prints have had at the time? Editor: So, because they're prints, they could reach a wider audience than a painting, and teach more people about the saints? Curator: Precisely. And beyond just visual communication, who was consuming these images? Were they affordable to the common person? How might social class impact who got to learn about Saint Werenfridus, and how he was perceived? Consider the contrast between the labor-intensive engraving process and its eventual distribution as a commodity. Editor: So the material realities – who made it, how it was made, and who could access it – all shape how we understand the image today. Curator: Exactly. It invites questions about labor, class, and the economics of image production in the Baroque period. It also reminds us to value those skills. It is through this lens that we see past just the visual, but acknowledge it as a commodity. What do you make of it now? Editor: I now understand how prints like this connected artmaking to a whole web of social and economic factors. It gives me a different view of it, rather than simply art on the wall. Thanks for your help.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.