Saint Frederick of Utrecht, from Saints of the North and South Netherlands 1650

0:00

0:00

drawing, print, paper, engraving

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

baroque

# print

#

figuration

#

paper

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: 440 × 315 mm (image/plate); 515 × 375 mm (sheet)

Copyright: Public Domain

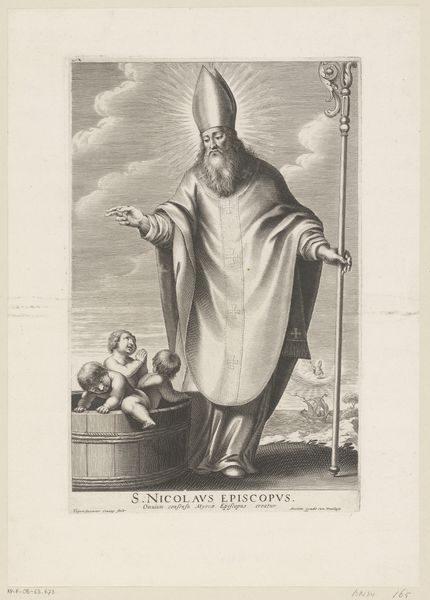

Curator: Here we have Cornelis Visscher's engraving of "Saint Frederick of Utrecht, from Saints of the North and South Netherlands," created around 1650. It's part of the Art Institute of Chicago's collection. Editor: Immediately, the precision and detail catch my eye. You can practically feel the weight of his garments, rendered through incredibly delicate lines etched into the paper. Curator: Absolutely. Visscher was known for his skill with the burin. What strikes me is the calculated role that prints such as this would play. They helped to solidify and spread particular ideas, not just of religious figures, but about the cultural identity of the Netherlands. Editor: A cultural technology, if you will. It raises the question: What does mass production mean for depictions of saints, especially considering their historical association with costly, unique, devotional objects? This wasn't painting but a method that brought Saint Frederick to more accessible settings. The materials say so much. Curator: Exactly. The proliferation of these images shaped popular perception, and also potentially dictated artistic choices in other media as artists sought to replicate what prints had popularized. Frederick's representation is far from neutral; he’s very intentionally positioned within a very specific, Netherlands context. Editor: Looking closely, the patterns on his cloak are fascinating. You can almost trace the maker's movements. It underscores labor, design, and the socio-economic web linked to production and, subsequently, devotion. It takes time, effort, and skill to replicate complex patterns like this using engraving tools, and the choices made for this Saint's attire make clear decisions on material wealth as tied to Godliness. Curator: A tension the Dutch grappled with during the Golden Age, as they navigated wealth and Calvinist principles. Visscher uses the print medium itself to actively participate in these societal dialogues, offering a visual shorthand for the period’s concerns and self-perception. Editor: And perhaps to make it commercially appealing. Even divine images participate in consumer economies. I think this changes my perception about 17th-century prints of the Saints: while obviously not idols themselves, the availability and details surely influenced personal religious views, especially considering their place and circulation through a more Protestant country. Curator: Precisely! Prints held complex social and ideological weight. They influenced lives then, and help us understand their world now. Editor: Thinking about this in terms of production gives us great insight to the life and commerce that was then!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.