photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

landscape

#

photography

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

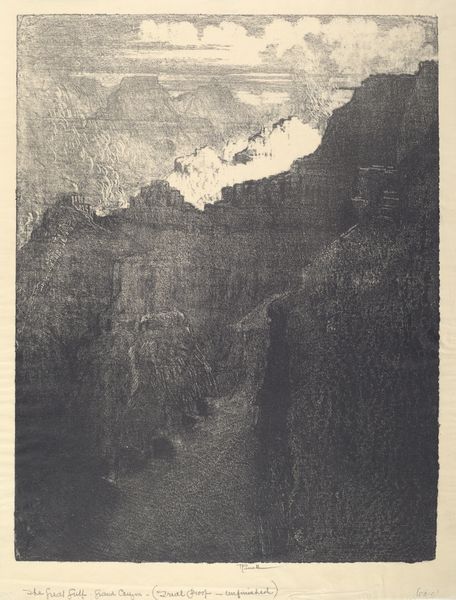

hudson-river-school

#

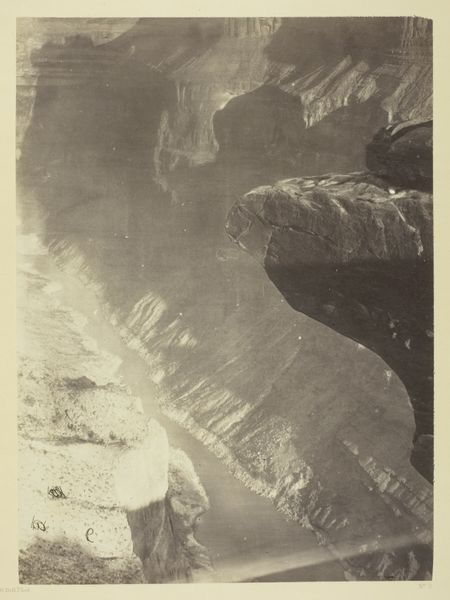

realism

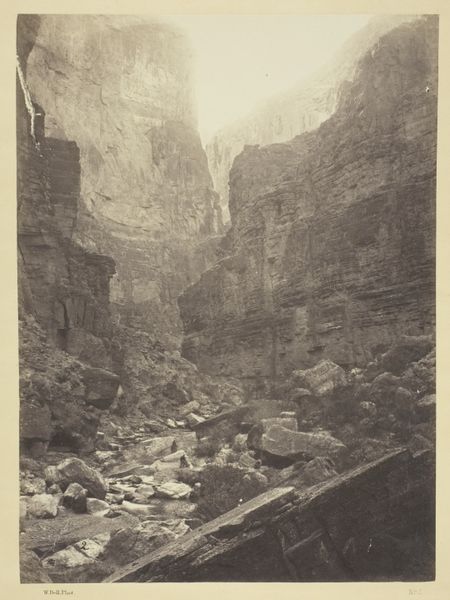

Dimensions: image: 27.5 x 20.3 cm (10 13/16 x 8 in.) sheet: 35.5 x 28.1 cm (14 x 11 1/16 in.) mount: 50.8 x 40.5 cm (20 x 15 15/16 in.)

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

Curator: Okay, let's dive into William H. Bell's gelatin-silver print, "Rain Sculpture, Salt Creek Canon, Utah" from 1872. Isn't it something? It really pulls you in with those textures. Editor: Absolutely, it strikes me immediately as desolate, yet strangely captivating. It’s a study in erosion and resilience, isn't it? Like looking at the wounds and wisdom of the Earth itself. Curator: Exactly! I mean, the way he's captured those ridges, like frozen waterfalls, almost... and knowing this was done so long ago, it’s like time travel! Do you think Bell saw himself as documenting the landscape, or something more...mythic? Editor: I think it's both. There's a clear documentary impulse—a desire to capture the West's rugged grandeur as part of nation-building—manifest destiny in photographic form, if you will. But the framing and tonal range elevate it beyond mere documentation. Look how those deep shadows contrast against the highlights; they speak to something profound about the human relationship to the land. And whose relationship is centered? Curator: Hmm, it does speak to expansion, to taking ownership, which certainly casts a shadow… However, I still sense an attempt to depict something purely... visceral, perhaps even a sort of echo of ancient processes… and consider the sheer physicality of dragging those glass plates around, developing on site. Editor: Yes, but that visceral quality is inherently mediated by Bell's gaze. The land isn't just "there"; it's being actively represented and consumed. Think about how these images were circulated back East—what ideas about the West were they reinforcing, and at whose expense? This romantic vision often overshadowed the Indigenous peoples and their intimate, sustainable relationships with the same landscape. Curator: Okay, a point very well taken…Still, to focus solely on the exploitative aspect feels reductive to me. I keep returning to this question of decay, beauty...of natural, impartial power… maybe even the sublime! What did all this mean to the indigenous peoples who had to see their sacred grounds turned into “a landscape”? Editor: I'd say that thinking about the sublime needs to involve also confronting difficult questions about whose sublime gets centered and why. The romantic framing flattens this into picturesque views. These landscapes also were the lands inhabited by many tribes; the photographs actively overwrite indigenous presence by turning it into ‘empty’ sublime nature. Curator: Mmm… Food for thought, certainly. I come away feeling it’s a piece steeped in duality; nature’s indifference mirroring society’s progress and how it has, and still is, dealing with that concept. Editor: Yes. I’m left considering how photography participates in larger power dynamics— who has the right to represent, to define, to consume? This isn't just a photograph of a pretty canyon, and those views have historically blinded folks for generations.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.