photography, albumen-print

#

landscape

#

street-photography

#

photography

#

historical photography

#

wedding around the world

#

ancient-mediterranean

#

orientalism

#

cityscape

#

street

#

albumen-print

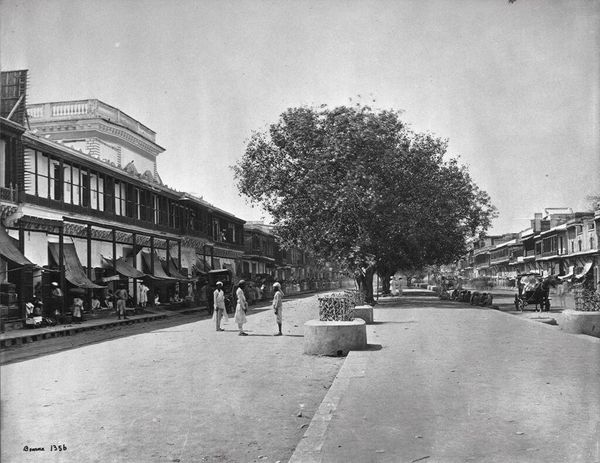

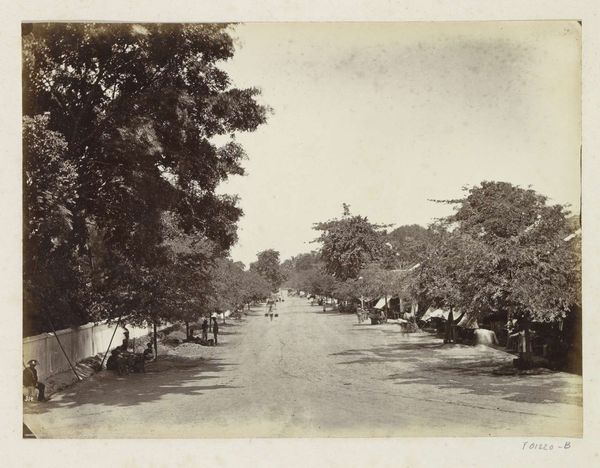

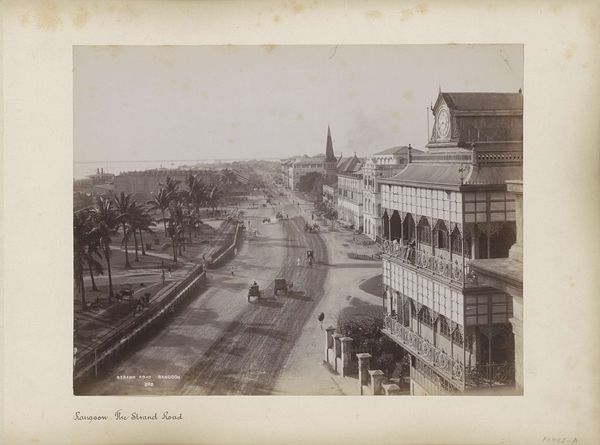

Dimensions: height 220 mm, width 286 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Let's delve into this remarkable photograph titled "View of Chandni Chowk in Shahjahanabad, Delhi, India," captured by Samuel Bourne between 1865 and 1870. It's an albumen print, which was a popular method at the time for its sharp details and tonal range. Editor: It has this very subdued feel about it. The sepia tones lend it a sense of nostalgia, almost like a distant memory. You can almost feel the heat and dust of the street despite its quiet stillness. Curator: Bourne's work offers valuable insight into the socio-political conditions of colonial India. Photography during this era wasn't just documentation, it actively participated in constructing a specific image of the 'Orient' for Western audiences. It played into narratives of empire. Editor: Absolutely, it is impossible to disassociate these images from colonialism. The apparent "authenticity" of the photographic medium created an almost irrefutable sense of truth, which then could easily be manipulated for imperialist agendas. Consider the framing itself – is this truly an objective 'view', or is it carefully constructed to communicate something specific about the 'exotic East' versus 'rational West'? Curator: It’s a calculated portrayal. Notice how the wide street creates a sense of order, perhaps a deliberate contrast to the bustling markets we might expect. This representation potentially minimizes any signs of resistance or social disruption. The almost vacant space speaks volumes. Editor: Exactly! The relative absence of people despite the signs of commerce hints at the control and imposed order by colonial power. Even seemingly neutral cityscapes can participate in power dynamics. Whose gaze are we adopting? How did the subjects react to being photographed in this context? The silences around the image can be very telling, perhaps hinting at both visible presences and erasure of identities in historical records. Curator: It allows us to reflect critically on how photographic representation reinforced the colonial narrative of control. Bourne’s photographs need to be understood not merely as records, but as constructions shaped by ideology and the intended audience back in Britain. Editor: The act of seeing is never neutral. Examining pictures like this requires confronting uncomfortable questions about history, power, and the ongoing impact of colonialism on visual culture. Appreciating beauty alongside the difficult political truths that inform the work enriches our comprehension, allowing it to move beyond face-value perception into critical consciousness.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.