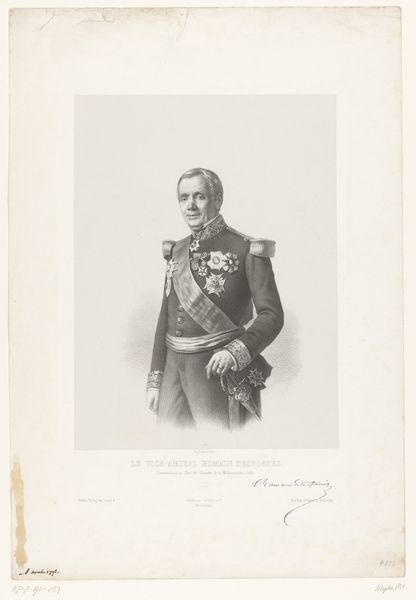

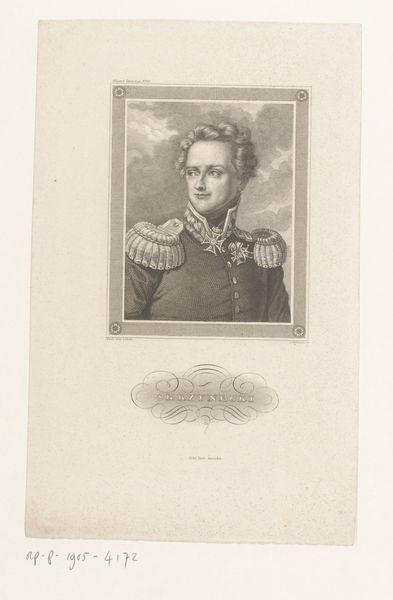

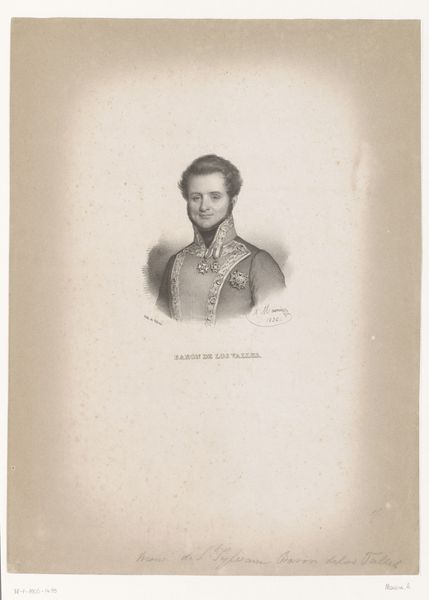

drawing, print, engraving

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

neoclacissism

# print

#

pencil drawing

#

engraving

#

realism

Dimensions: height 500 mm, width 385 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Ah, this engraving always stops me in my tracks. This is "Portret van Jean Casimir de Brunet," attributed to Carel Christiaan Antony Last. It’s a fascinating piece; the Rijksmuseum dates it between 1833 and 1876. It appears to be made up of a mix of print and pencil drawing elements. Editor: Immediately, the somber gravitas leaps out at me! The detail, especially around the medals, is incredible. But it also feels… a little staged, wouldn’t you say? Very much a representation of power. Curator: Absolutely. Think about the context. This is Neoclassicism meeting Realism. The subject, likely a man of some influence. Those medals are shouting, "Look at my achievements!" He is literally wearing his political achievements. Editor: Which, of course, raises questions about accessibility, doesn't it? Who was this image meant for? Was it a broad public, or a select group meant to admire and respect Mr. Brunet? Curator: I'd wager the latter. Engravings like this were often commissioned or distributed within specific social circles, affirming status and solidifying power dynamics. It also reveals an ambition, or need for public acknowledgment. You see these medals are very deliberately shown. Editor: The artistry is undeniably captivating. But as much as it draws you in to examine the artistry of the print, it also acts as a bit of a mirror. Curator: How so? Editor: Well, portraits always reflect something about the society that produces them, right? In this case, we see the performance of authority. Jean Casimir de Brunet isn’t just a man; he's a symbol, crafted through careful artistic choices. Curator: Exactly! It's this tension, I think, that gives the work its staying power. Beyond the skilled rendering, there's a layer of social commentary that resonates. We, as viewers are implicated and included in its study of status. Editor: Ultimately, I come away admiring the technique, but pondering what it really means to create and consume these images. It speaks volumes, and subtly criticizes too. Curator: And for me, it’s a reminder that every portrait—whether painted, drawn, or engraved—is a collaboration between artist, subject, and society. They're each engaged in a negotiation of identity, in visual form.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.