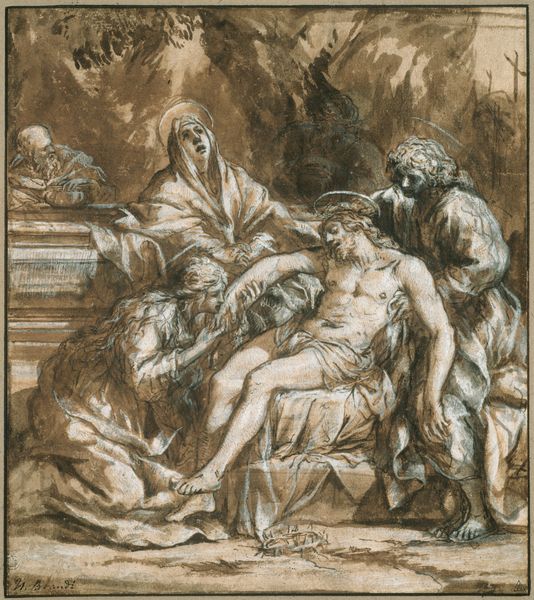

painting, oil-paint

#

baroque

#

painting

#

oil-paint

#

figuration

#

history-painting

#

nude

Dimensions: overall: 81.7 x 68.5 cm (32 3/16 x 26 15/16 in.)

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

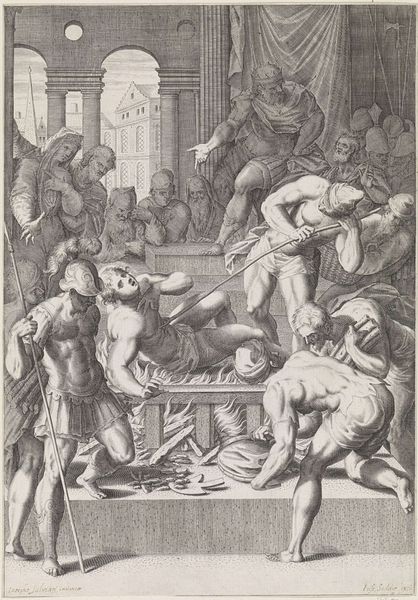

Curator: This is Jean Baptiste de Champaigne’s, "The Martyrdom of Saint Lawrence," dating back to about 1660. It's an oil painting that depicts quite a dramatic scene. Editor: My goodness, what a powerfully unsettling image! The pallid body stretched over the grate—it makes me shiver. It's rendered with such a tender vulnerability, a fragile humanness. Curator: Indeed. Champaigne has very carefully arranged the scene and utilized the materiality of the paint. Note the distinct brushstrokes; the layers upon layers that construct the theatrical setting. The social context, too, is crucial. History painting served to instruct and inspire through depicting moral and heroic narratives like this story of Saint Lawrence. Editor: It's difficult to tear your eyes away, despite the obvious suffering. The scene seems constructed to invite this very contemplation. Is it a beautiful horror or a horrific beauty? I think the baroque theatricality really leans into the paradox. The contrast between the saint's pale skin and the darker surrounding colors really jumps out to me. Curator: Precisely. And the use of oil paint allowed for a smooth blending and building up of forms, especially observable on Saint Lawrence. He isn't just a martyr, he’s carefully posed; even objectified to some extent by the artist's technique, a product in his world. What do you think that implies about the position of the artisan, or consumer? Editor: Oh, I see what you mean. I'm also thinking about how the artist uses light—it almost feels heavenly shining down and illuminating his expression as if communicating that he's being uplifted spiritually during this ordeal, not just physically harmed, while the composition brings to attention both a divine mercy, and the grim mechanics of his suffering. It feels both intensely present, and distantly observed. Curator: Ultimately, this is an exercise in image-making that engages with religious fervor as much as it engages with labor practices inherent in 17th-century art production. It invites considerations of materiality and craftsmanship within wider historical forces that condition artistic agency and determine the means and nature of this scene, like production, commissioning and distribution Editor: Looking at it, I suppose the core thing is how it reminds us of how, amidst even the darkest and most organized brutalities, a transcendent spirit seems to ignite something akin to…well, hope. That’s powerful, I think.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.