carving, sculpture

#

carving

#

sculpture

#

asian-art

#

stoneware

#

sculpture

#

ceramic

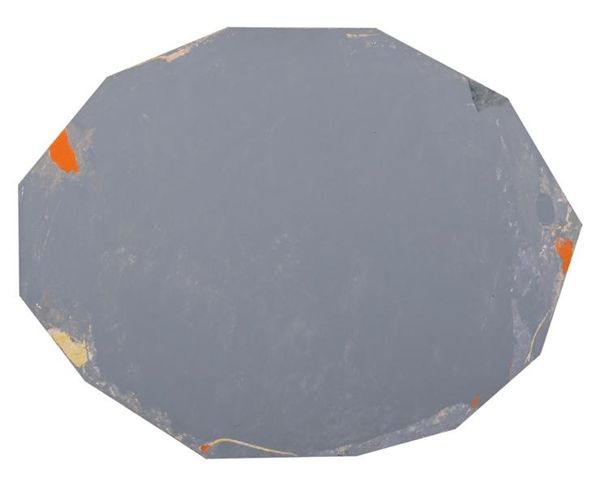

Dimensions: 1 1/8 x 6 3/16 x 8 1/4 in. (2.86 x 15.72 x 20.96 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: We’re looking at a beautiful Ink Stone made around 1623, crafted by Wen Yu-yang. It's currently held in the collection of the Minneapolis Institute of Art. Editor: It looks like a little island, doesn’t it? So serene, with this calm, flat sea in the middle surrounded by frothy, sculptural waves. You almost want to dip your toes in it! Curator: Absolutely. The concept of the ink stone is fascinating in and of itself—central to the scholarly practice in East Asian cultures. Beyond its functionality, an ink stone like this becomes a space to negotiate the identities of scholar-officials during times of social change. Editor: The swirls around the edges feel almost alive. Are they flowers or clouds or mythical creatures? Maybe they're the dreams dreamt over a scholar’s desk, ready to be turned into poetry! There's a lovely ambiguity to them. Curator: I appreciate you pointing that out. It reflects the kind of literati aesthetics it's inspired by: with references to Daoist or Buddhist imagery, these motifs elevated the status of both the object and its user, differentiating it from pure craftsmanship. The carving is quite elaborate. Editor: And what would those distinctions mean in a society where artists, poets, and scholars had such an unstable place in the larger cultural dynamics? Like, who got to decide what elevated something? It feels almost… defiant to put so much artfulness into something as quotidian as a desk tool. Curator: That's a key tension—the stone embodies the literati ideal while challenging fixed social hierarchies. I see this piece as an intersection of politics, art, and the formation of identities in Ming China. Editor: Hmm, that does make you wonder about Wen Yu-yang's personal stance, doesn't it? I wonder if, while they were carving it, they knew their creation would become a symbol. Maybe the quiet intensity I'm seeing isn't just stone but the concentrated fire of one person's rebellious creativity! Curator: An insightful perspective. Considering the social context and this artist’s engagement opens richer interpretations beyond just aesthetics or utility. Editor: Well, sometimes the simplest objects hold the biggest secrets, right? Curator: Indeed. I've really come to see it anew through your lens.

Comments

minneapolisinstituteofart about 2 years ago

⋮

The stone slabs that artists used to prepare ink were highly valued. The quarries at Hsi-hsien in Anhui province and at Tuan-chou in Kwangtung yielded fine slatelike stone that had the right porosity, hardness, and grain to make good grinding utensils. Many Ming and Ch'ing dynasty stones were embellished with carved décor. This example has a cresting wave pattern on both the top and bottom surfaces. The bottom, shown here, includes a twenty-six-character inscription carved in archaistic script followed by the date 1623, signature, and seal of Wen Yu-yang.

Join the conversation

Join millions of artists and users on Artera today and experience the ultimate creative platform.