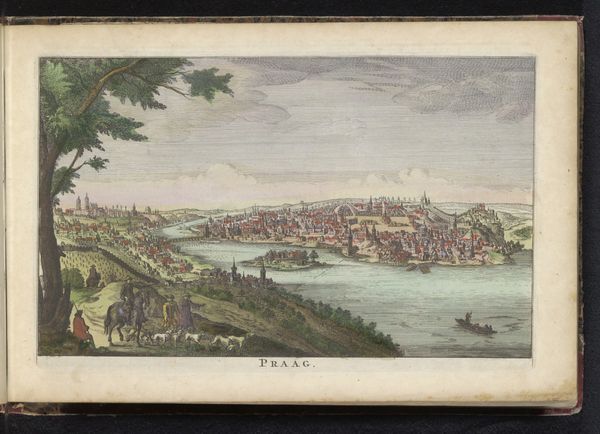

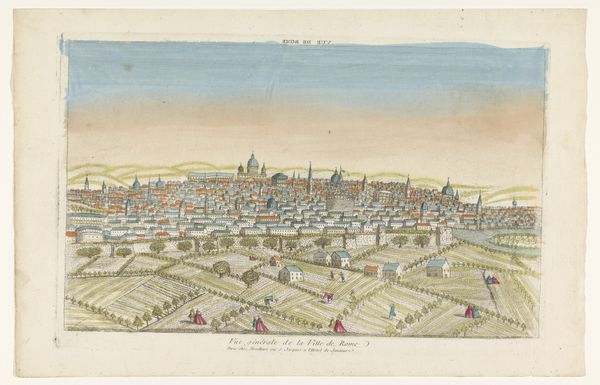

print, watercolor

#

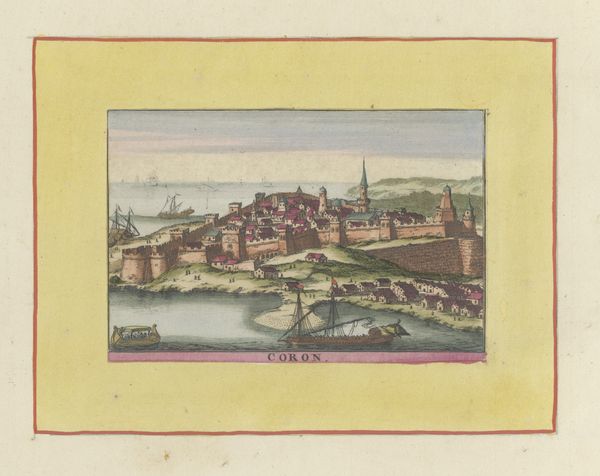

water colours

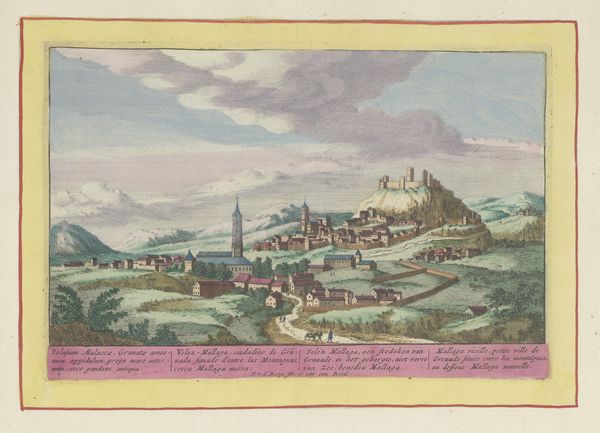

#

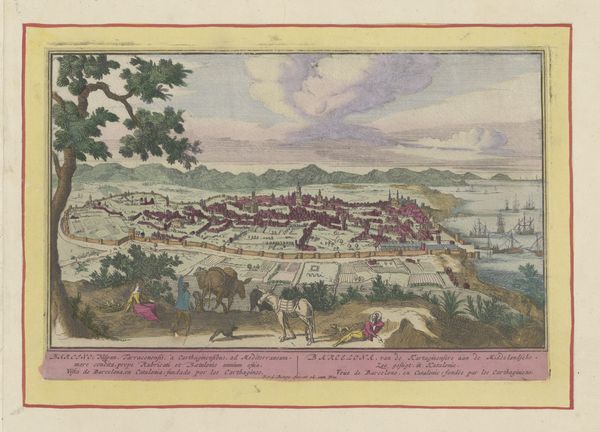

baroque

# print

#

handmade artwork painting

#

watercolor

#

cityscape

#

earthenware

#

watercolor

Dimensions: height 171 mm, width 258 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

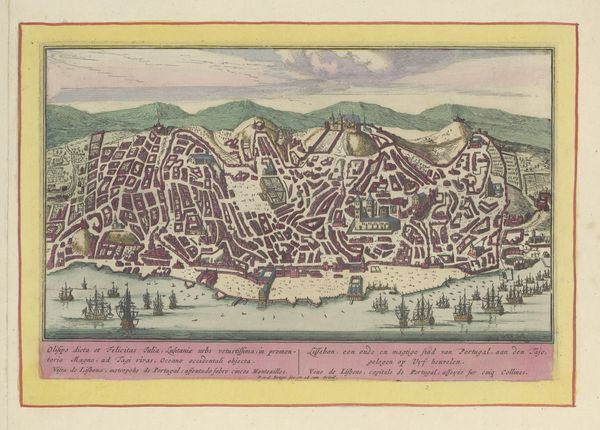

Curator: Here we have "View of the City of Toledo," a baroque cityscape rendered between 1694 and 1737 by Pieter van den Berge. It's currently part of the Rijksmuseum collection. What's your immediate reaction to this work? Editor: It's intensely detailed, almost miniaturized in its precision. There’s something about the clustering of the buildings, the way they seem to erupt from the landscape, that suggests a kind of collective human striving—ambition etched into the very form of the city. Curator: Indeed, it's interesting how van den Berge chose to portray Toledo. This print, crafted using watercolors, offers us a window into the early modern period's fascination with urban centers and their representation. Consider the implications of creating and disseminating such images. Editor: Absolutely. I see this not just as a benign cityscape but as a carefully constructed visual argument. The composition, which positions the city atop a hill, almost like a fortified citadel, implicitly comments on power structures, territorial control, and the historical narratives that have shaped Toledo’s identity. Curator: The meticulous details speak to a growing awareness among European city dwellers of their location’s rising power in commerce, the development of the city in relation to nature and even in art history, too. Editor: I agree, this attention to detail, it seems less about an objective record and more about crafting a certain perception, possibly obscuring marginalized voices or downplaying social stratification. The question I think about here is, "Who is this for?" and "What specific message does this transmit or uphold?" The people along the river feel like a superficial add-on. Curator: That's a critical question, of course. Cityscapes like these were commissioned for various reasons – civic pride, cartographic documentation, or simply as souvenirs for wealthy travelers. These pieces promoted the urban image. How it translates in contemporary culture really relies on the audience engaging it critically. Editor: Ultimately, it’s a reminder that no artwork, even seemingly straightforward depictions, exists outside of the complex web of social, economic, and political realities. Looking at it this way is a key lesson in seeing how art and activism can promote critical readings and political awareness. Curator: I completely agree, it becomes a tool for examining not only the aesthetic preferences of the past but also the ideological underpinnings of urban development.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.