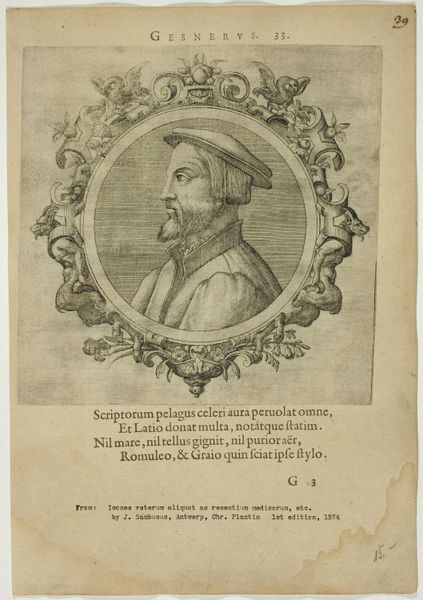

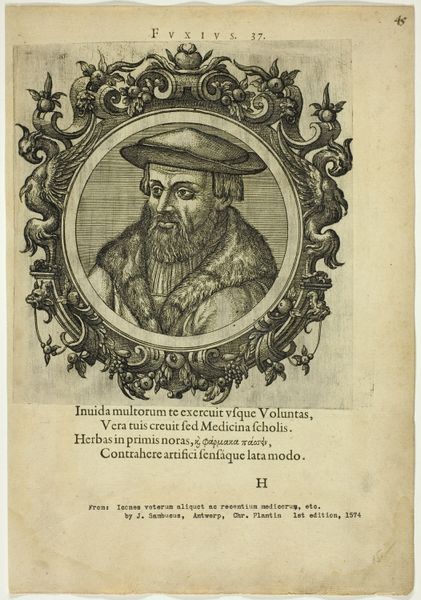

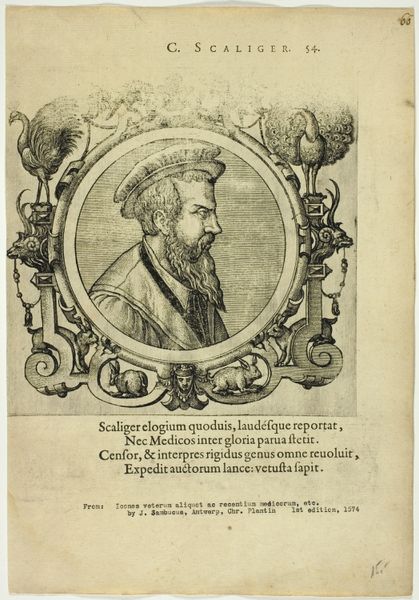

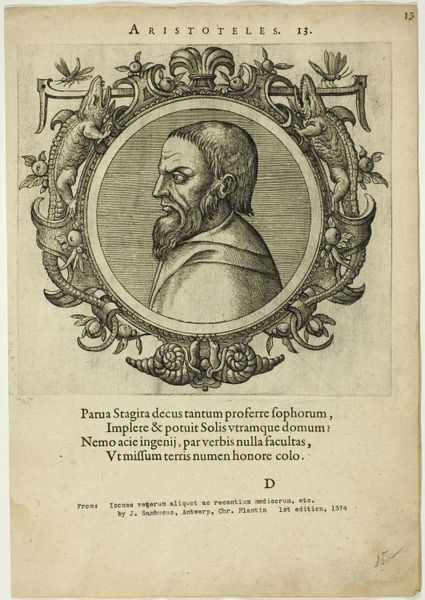

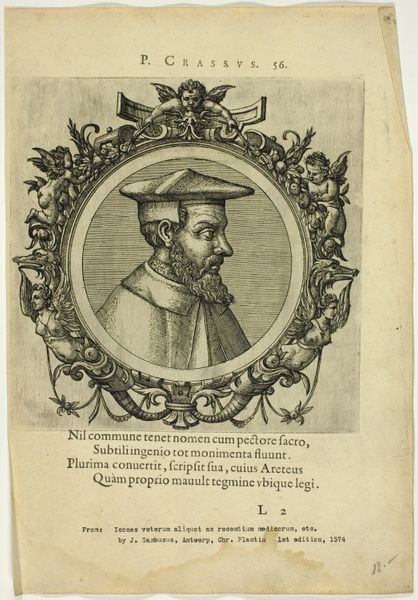

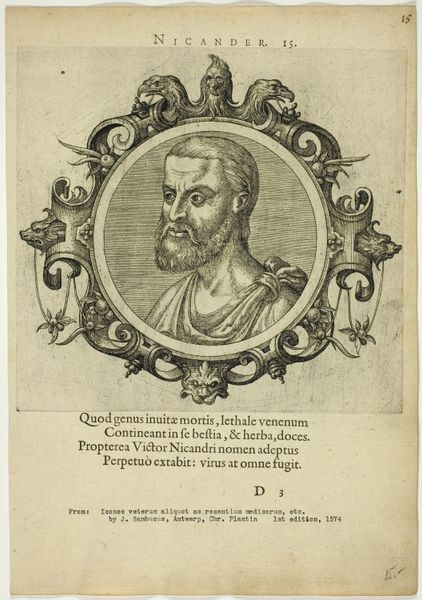

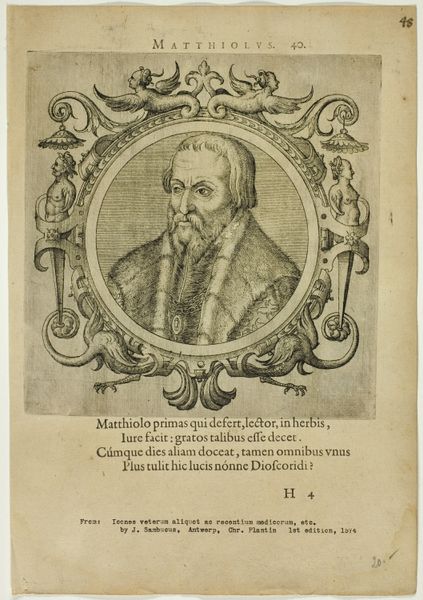

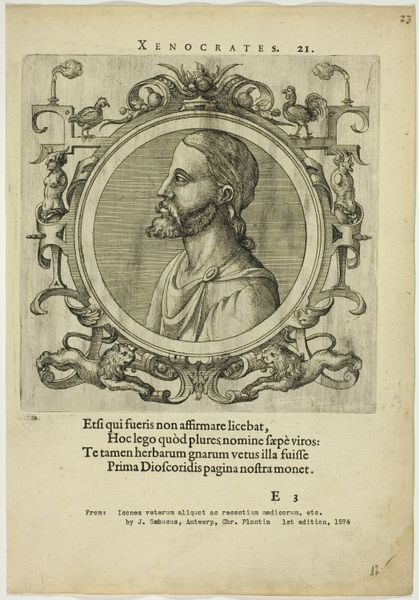

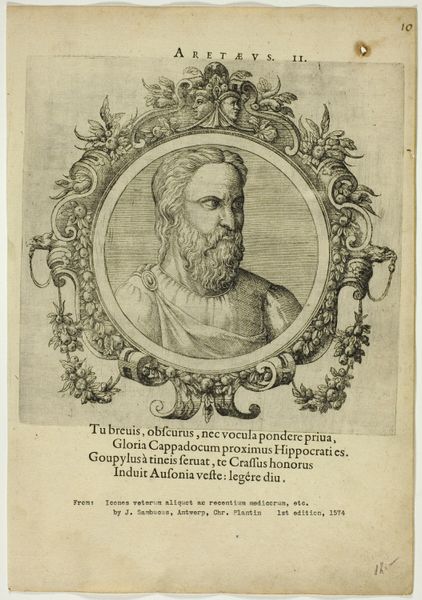

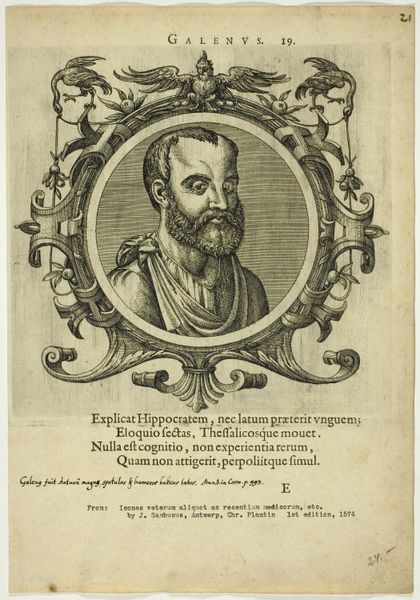

drawing, print, etching, paper

#

portrait

#

drawing

# print

#

etching

#

mannerism

#

paper

#

11_renaissance

Dimensions: 192 × 186 mm (image/plate); 311 × 215 mm (sheet)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Welcome. Before us is the “Portrait of Cornarius,” a print created possibly in 1574, etched by Johannes Sambucus. It’s currently housed here at the Art Institute of Chicago. What’s your immediate reaction? Editor: My eye is immediately drawn to the incredibly detailed etching work, especially within the ornate frame surrounding the portrait itself. I’m curious about the type of paper used, and how that influenced the crispness of the lines achieved in the printmaking process. Curator: Indeed. Beyond the medium, let's consider Cornarius himself. He was a prominent physician and classical scholar. This portrait likely served as a frontispiece for one of his publications. I think about how scholarly authority was constructed and represented in the Renaissance. Editor: Interesting. From my perspective, understanding the societal role and the labor involved in creating this imagery offers another layer of richness. The frame, packed with animals, seems like its own little production teeming with life. And consider the economic factors – who commissioned this print, who was it intended for, and how did the cost influence the materials and techniques used? Curator: Exactly! It's intersectional. The visual language employed here--the pose, the attire, and the inclusion of his name--work together to broadcast Cornarius's elevated social standing. It's a commentary on status and the intellectual elite. Editor: The visual encoding, I agree, acts as advertisement. The quality and fineness communicate Cornarius’ commitment to his craft. Every mark must have demanded extreme control on behalf of the artist and likely lengthy hours dedicated to production. And what of Sambucus the artist? How did the printer or publisher shape or limit the creative endeavor through material constraints and budgetary pressures? Curator: These are critical questions to keep asking. Ultimately, this print, and so much artwork from this period, reminds us that art is deeply enmeshed within layers of power. Cornarius used his own image strategically to maintain a presence within intellectual discourse, crafting an image for posterity. Editor: A printed, multiplied presence. Exactly! To look at how an artwork is presented or received without questioning the concrete decisions and conditions by the maker obscures much of its true power. This piece really invites one to think more deeply about labor as well as artistic processes in the 16th Century. Curator: I find myself circling back to how portraiture through this lens becomes not just about representation but a strategic exercise in social identity. Editor: For me, it brings focus on how those decisions in making reveal the historical texture and materiality of their moment.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.