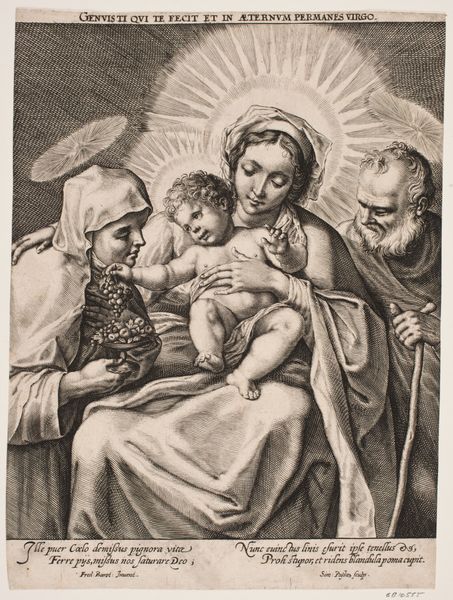

print, engraving

# print

#

mannerism

#

figuration

#

group-portraits

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 257 mm, width 195 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This engraving, dating from around 1579 to 1615, is titled "Holy Family with Saint Clare of Assisi" and is currently held at the Rijksmuseum. It's attributed to Dominicus Custos, and strikes me as a quintessential example of late Mannerism. Editor: It has such an enclosed, almost stifling feel. There's a tightness to the figures and the stark contrast in the hatching adds to a sense of emotional constraint. Curator: Yes, look closely at the composition. It compresses these figures into a very shallow space. The way Saint Clare's dark habit juxtaposes with the bright halo around Mary, the contrasting tones speak volumes. Consider what it meant to produce this. Engravings involved intense labor and skill; each line etched into the metal plate reflects the artisan’s hand and commitment. Editor: Absolutely. This work encapsulates a powerful tension. The inclusion of Saint Clare alongside the Holy Family suggests a specific dedication or patronage. Dominicus Custos, through his skilled printmaking, situates this image within complex religious and social networks. Note the inscription in Latin. It alludes to conversion, "Ego dilecto meo et ad me conversio eius." Whose conversion are we witnessing? What power structures are being reinforced, especially through this idealized, arguably exclusionary, representation of holiness? Curator: Think about how such prints functioned in society, circulating images and reinforcing religious doctrines, which helped construct a visual language available to a broad audience. This allowed the spread of religious imagery into domestic settings and contributed to private devotional practices. Editor: The work prompts reflection on gender, too. Clare, a woman holding what appears to be the Eucharist chalice or a monstrance, complicates conventional images of female piety in that historical moment. I would say that engraving's visual austerity echoes and reinforces this period's often very oppressive attitudes. The formal restraint mirrored social expectations. The lack of dynamism, compared to earlier Renaissance works, signifies a tightening control over both religious expression and artistic practice. Curator: And from a material perspective, that contrasts to, say, painted devotional works, the multiplication made it widely accessible, influencing far more devotional acts than unique pieces could. That multiplication democratizes the religious message and material access. Editor: By examining these intersections—gender, class, religious doctrine—the engraving speaks to broader sociopolitical realities. Thank you for allowing me the space to explore the work more deeply! Curator: The pleasure was mine. Looking closely and sharing diverse perspectives only deepens our experience and interpretation.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.