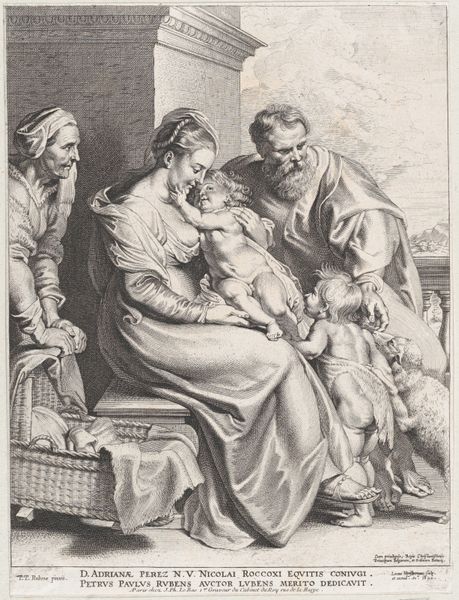

The Holy Family with Saint Elizabeth and Saint John the Baptist 1775 - 1785

0:00

0:00

Dimensions: Sheet (Trimmed): 6 5/16 × 4 5/8 in. (16.1 × 11.7 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: This is an engraving of "The Holy Family with Saint Elizabeth and Saint John the Baptist" by Robert Brichet. It likely dates to around 1775 to 1785 and is based on a painting by Peter Paul Rubens. Editor: The density of detail in this image strikes me immediately. It feels almost claustrophobic, the figures pressed together in a shallow space, heightened by the contrast between light and shadow typical of the Baroque style. Curator: Note how Brichet uses the engraving technique to render the texture of fabric, the softness of skin. Consider, too, the iconography: each figure has a purpose, reinforcing the central theme of familial sanctity, echoing established tropes of its time. Editor: I see the emotional warmth radiating from Mary towards Jesus—a tangible sense of maternal love underscored by their physical connection during breastfeeding. But Elizabeth and John's inclusion expands the familial bond, prefiguring a redemptive history that binds generations. Curator: Absolutely. The Holy Family motif becomes a vessel through which prevailing cultural values were communicated and circulated. It wasn’t just religious; it served as an example of order during social upheaval, perhaps reflecting contemporary anxiety about eroding class hierarchies or gender norms during that period. Editor: That context adds a compelling layer. Looking closer, even Joseph's somewhat paternal but slightly detached gaze speaks volumes about prescribed social roles. One may perceive a degree of emotional suppression despite the intimate family grouping. Curator: That is interesting. One can read the image as either celebrating, or interrogating conventional domestic expectations, depending on your view. What is unquestionable is that it gave accessible form to deep-seated beliefs. Reproductions like this made such depictions broadly consumable and reinforced how social norms should be read and received. Editor: Indeed, art acts as a crucial social mirror—not simply showing our aspirations but actively constructing them. Examining the provenance reveals it as "Du Cabinet de M' Poullain"—evidently a reproduction intended for collection within art enthusiast circles rather than specifically for religious viewing. It offers a curated, domestic experience. Curator: Yes. Brichet’s print shows not just religious iconography, but gives the idea that even engravings can be incorporated into sophisticated bourgeois life. It serves to educate as much as providing an emotional experience for the devout Christian patron, I’d suggest. Editor: Pondering these elements gives one much to reflect on indeed!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.