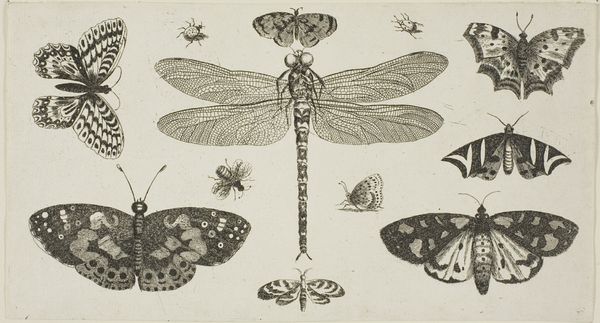

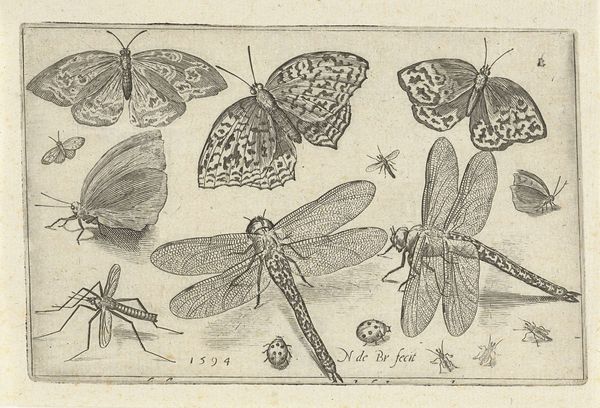

drawing, print, etching, engraving

drawing

baroque

etching

history-painting

engraving

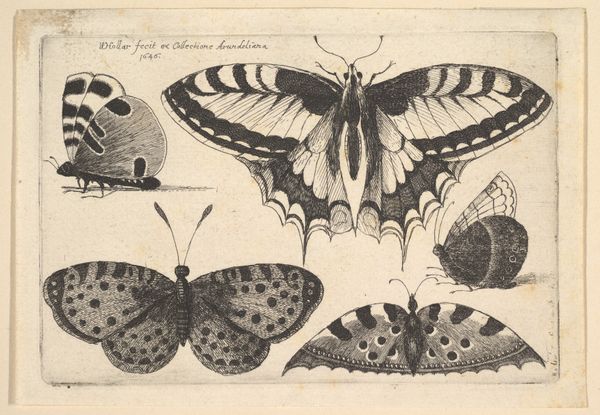

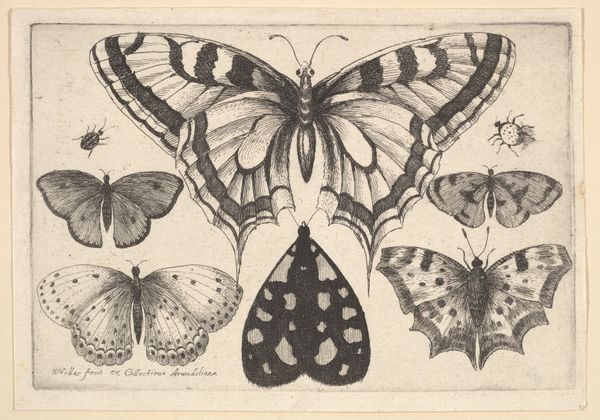

Dimensions: Plate: 3 3/16 × 4 5/8 in. (8.1 × 11.8 cm) Sheet: 3 11/16 × 5 1/8 in. (9.3 × 13 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

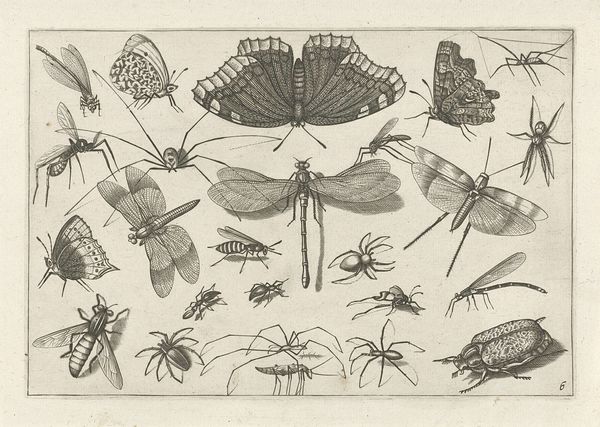

Editor: We’re looking at "Dragonflies and a bumble bee" by Wenceslaus Hollar, created in 1646. It’s an etching and engraving. The starkness of the composition—these insects arranged against a blank background—makes it feel very formal, almost scientific. What draws your eye in this piece? Curator: It is a fascinating study in line and form. Consider the density of the hatching, the strategic deployment of light and shadow. Notice how the artist meticulously renders each insect with an almost obsessive attention to detail. Editor: I do see that. It’s like he's celebrating their structures, each line defining a part. But why this intense focus? Is it just about scientific accuracy? Curator: The question you pose rests within its graphic syntax, consider Hollar’s calculated presentation—how the composition leverages visual space—dictates how we perceive form. His arrangement highlights contrasting textures: the solid wing of the dragonfly juxtaposed with the furry bumblebee. Such attention redirects interpretations. Does this change your original sense of 'scientific accuracy?' Editor: I see what you mean. He is manipulating my eye to notice particular qualities. It isn't just documentation. So it's about the *way* he's presenting them as much as *what* he's presenting? Curator: Precisely. The beauty emerges from the artist's intentional choices of perspective, line weight, and compositional organization; dissecting formal constructs delivers more perceptive meaning. Editor: That makes so much sense! I will certainly rethink my perspective moving forward. Curator: That is what art challenges us to do.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.