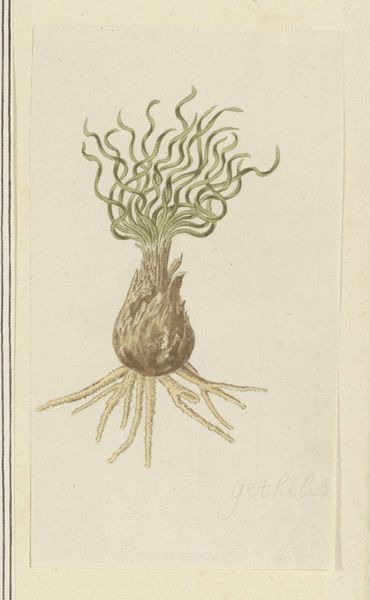

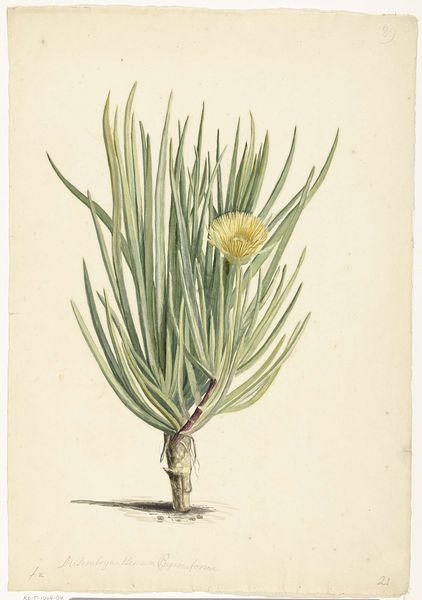

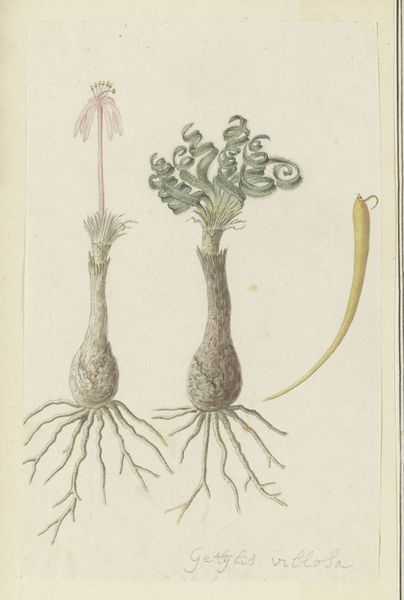

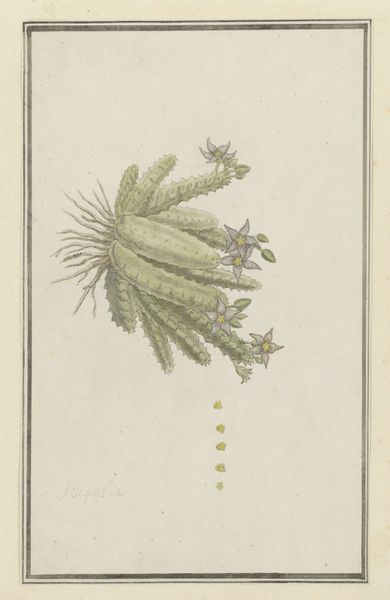

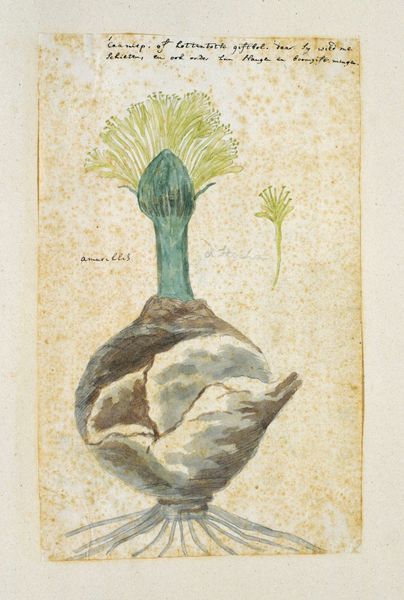

Boophone haemanthoides F.M. Leighton (Hottentots poison-bulb, or giftbol) Possibly 1777 - 1786

0:00

0:00

Dimensions: height 660 mm, width 480 mm, height 389 mm, width 496 mm, height mm, width mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: Here we have Robert Jacob Gordon's watercolor drawing of the *Boophone haemanthoides*, or Hottentots poison-bulb, dating back to possibly 1777-1786. It feels very detailed and somewhat surreal. How do you interpret this work beyond its obvious botanical intent? Curator: I see it as an artifact of colonial encounter, a visual record deeply embedded in power dynamics. Gordon, working for the Dutch East India Company, was charting and classifying the Cape. This botanical study isn’t just about the plant itself, but also about claiming knowledge and control over the land and its resources. Consider its purpose: these images served as tools to describe and essentially conquer nature for commercial exploitation. Editor: That’s a pretty strong indictment. Do you see anything positive in these detailed illustrations? Was there some good intention behind them? Curator: It's complex. Yes, there was scientific curiosity and, perhaps, even a degree of admiration for the natural world. But we cannot ignore the socio-political context. This detailed representation also renders the plant extractable and knowable, ready for appropriation. The act of naming—*haemanthoides*, Hottentots poison-bulb—is itself a form of ownership. Whose knowledge are we privileging? What local names and uses of this plant were overwritten in this process? Editor: So you see this botanical illustration less as a scientific document and more as a kind of visual colonization? Curator: Precisely. It highlights the role of visual culture in constructing narratives of dominance and shaping perceptions of the "other," whether that other is a plant or a people. Consider how this image might have reinforced European ideas about the "untamed" Cape, ripe for cultivation and exploitation. Editor: I never would have thought of it that way! It is jarring to consider the history embedded in what seems like an objective observation. Curator: It demonstrates the inseparability of art, science, and politics. It challenges us to see beyond the surface of an image and ask, "Who benefits from this representation, and at what cost?"

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.