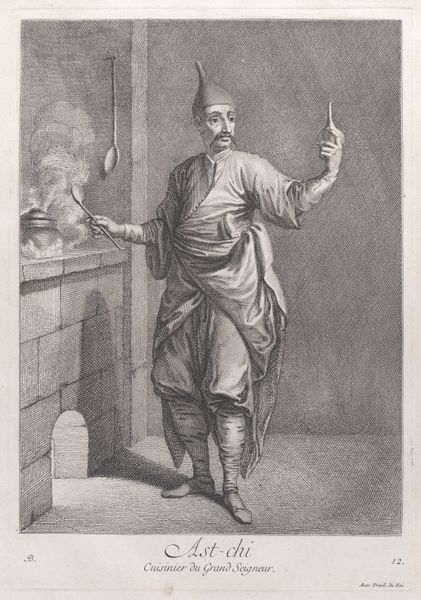

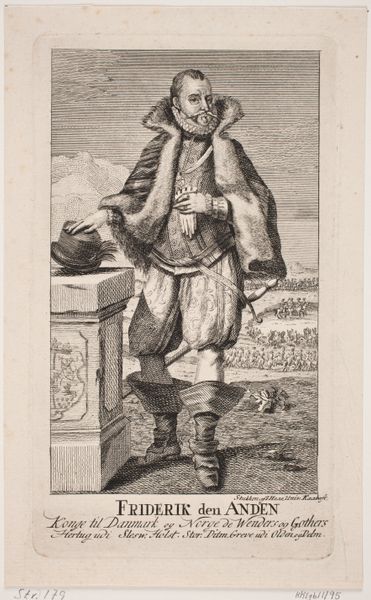

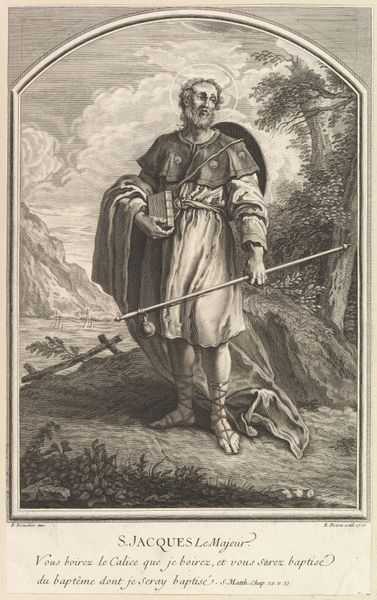

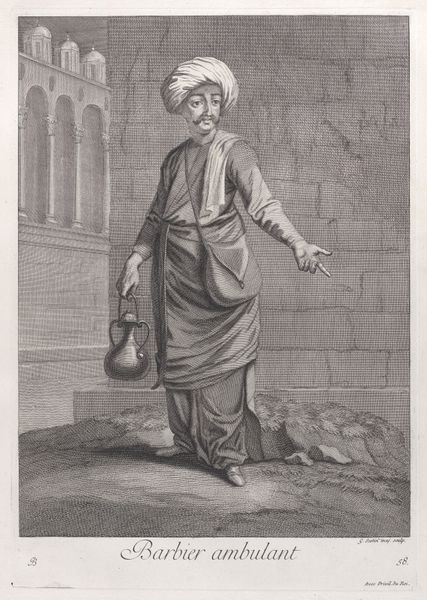

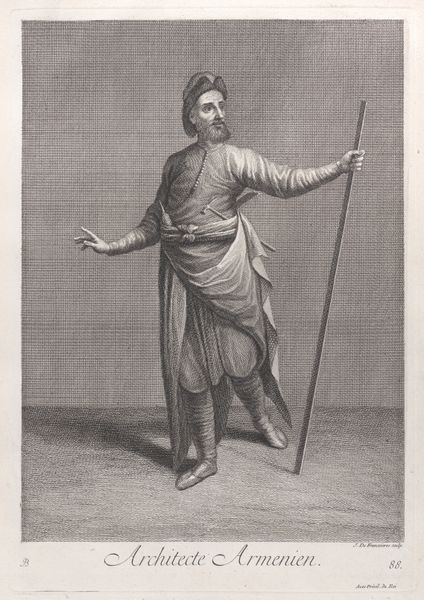

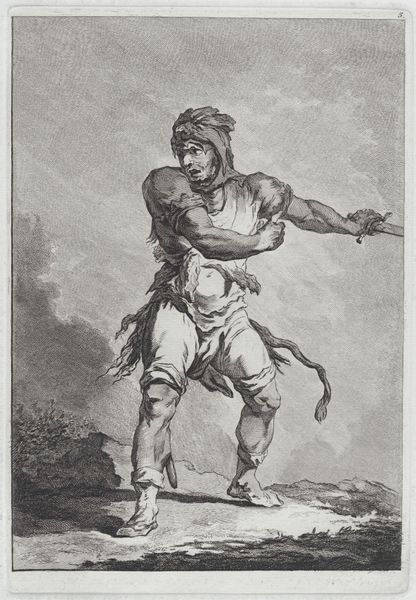

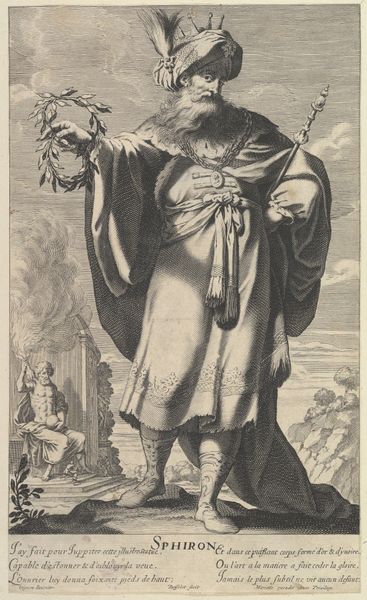

Leventi, ou Soldat de Marine, plate 38 from "Recueil de cent estampes représentent differentes nations du Levant" 1714 - 1715

0:00

0:00

drawing, print, engraving

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

baroque

# print

#

figuration

#

men

#

genre-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: Sheet: 16 7/16 in. × 12 in. (41.8 × 30.5 cm) Plate: 14 1/8 × 9 13/16 in. (35.8 × 25 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

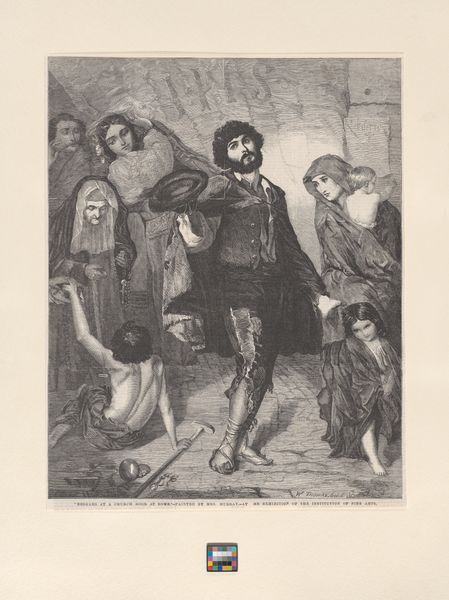

Editor: Here we have "Leventi, ou Soldat de Marine" by Jean Baptiste Vanmour, made sometime between 1714 and 1715. It’s an engraving, currently held at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. It shows a marine soldier…there's something almost theatrical about the pose, wouldn't you say? What strikes you most about this work? Curator: It's a fascinating example of Orientalism. These depictions, ostensibly ethnographic, served to reinforce European power dynamics. The image isn't just a portrait; it's a performance of dominance, reducing a complex culture to a type. Note the details--the exoticized clothing, the nonchalant posture. Who do you think this work was made for? Editor: I imagine it was made for a European audience, maybe wealthy patrons interested in far-off lands? Curator: Precisely. And what stories were they consuming along with images like this? What political climate would have supported such narratives? This print participates in constructing an "Other," marking differences, but also establishing hierarchies. Do you notice any aspects about this person’s attitude or the overall setting that might be idealized? Editor: Well, the soldier seems almost…posed, a little too perfect maybe? The city in the background seems peaceful, a bit like a stage backdrop. Curator: Exactly! The serene background naturalizes European conceptions of the Orient as something to be studied, classified, and ultimately, controlled. This piece invites us to confront the ways images have historically been used to justify imperialism. Editor: It’s definitely a lot to think about how a simple portrait can reflect much larger power struggles. Curator: Indeed. By engaging critically with these images, we can better understand the lasting impact of colonialism on our present. It also calls on us to interrogate what hasn't changed about art production and dissemination, as some oppressive forces endure through representation today. Editor: I learned how even seemingly simple images carry a lot of cultural and historical weight. It makes you look at art from a totally different angle. Curator: That's right! Analyzing such images challenges us to continually reassess whose stories are being told, and by whom, urging more conscious viewing.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.