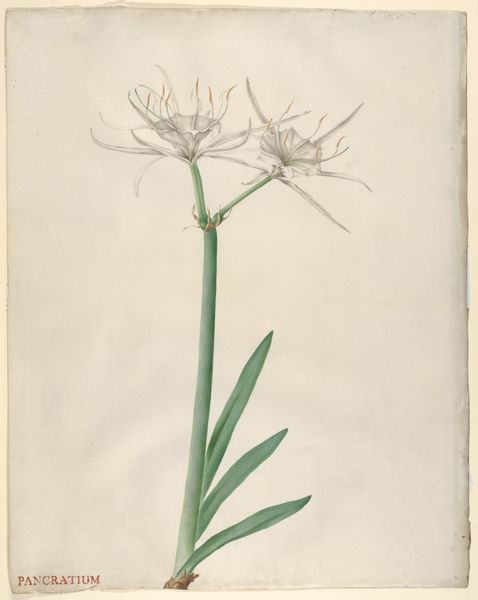

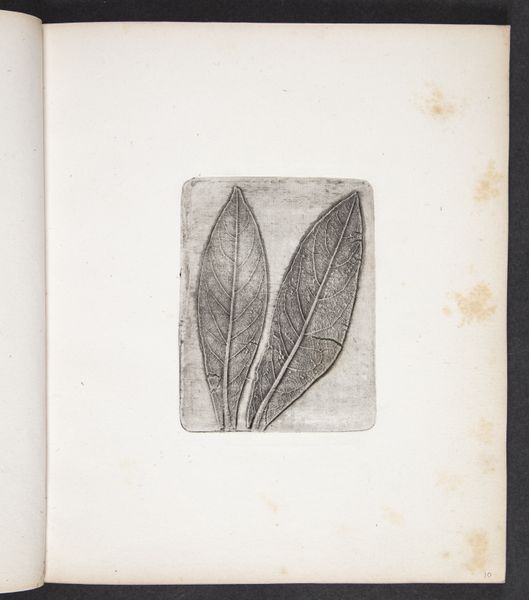

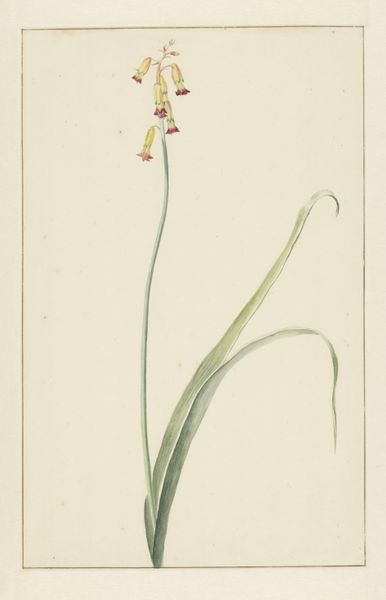

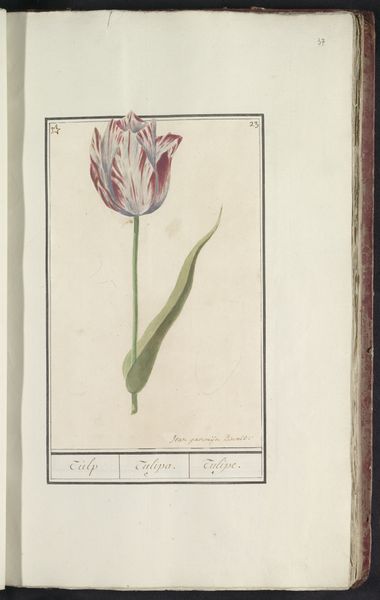

drawing, paper, watercolor

#

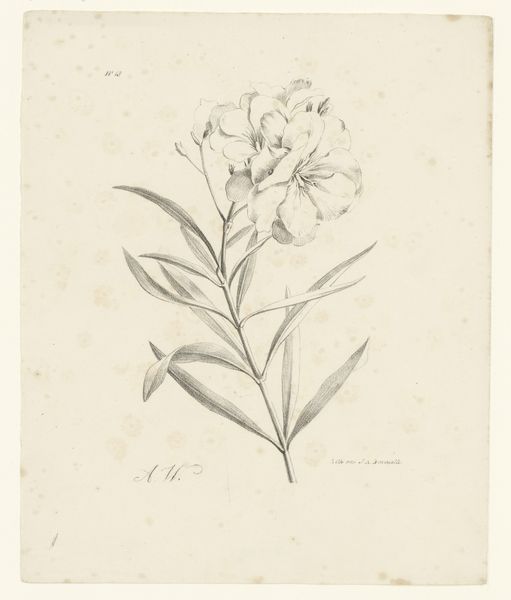

drawing

#

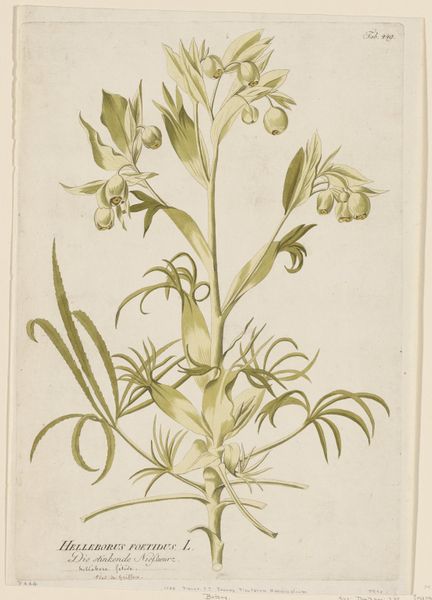

book

#

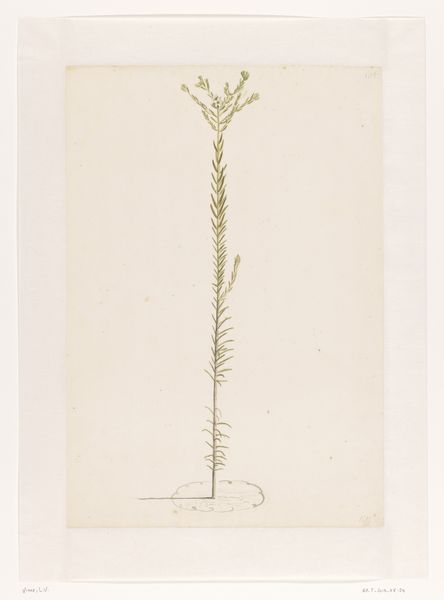

paper

#

watercolor

#

15_18th-century

#

line

#

watercolor

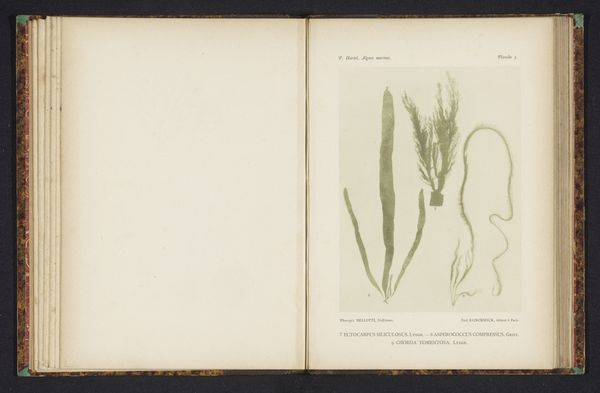

Dimensions: 20 1/4 × 15 7/8 × 2 5/8 in. (51.44 × 40.32 × 6.67 cm) (closed)20 1/4 × 34 1/8 × 2 1/4 in. (51.44 × 86.68 × 5.72 cm) (open)

Copyright: Public Domain

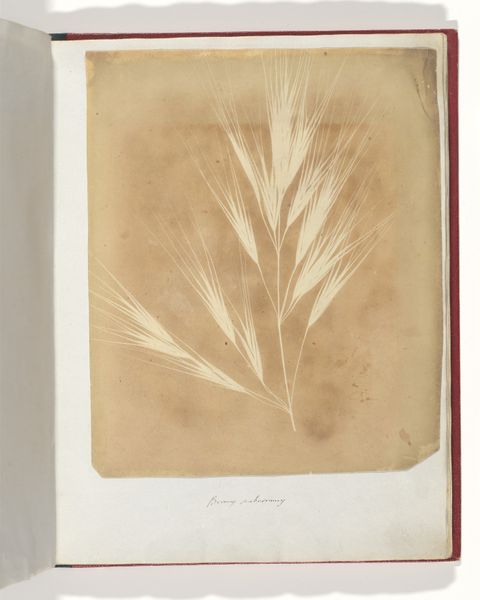

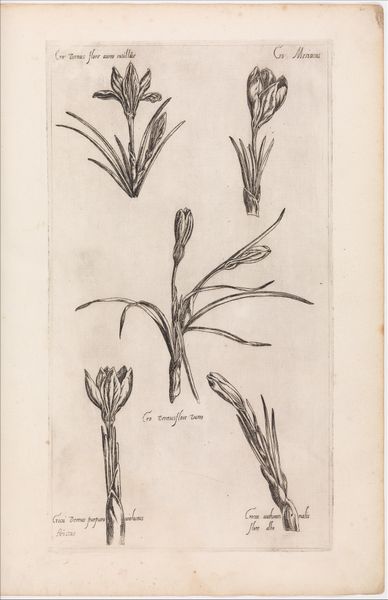

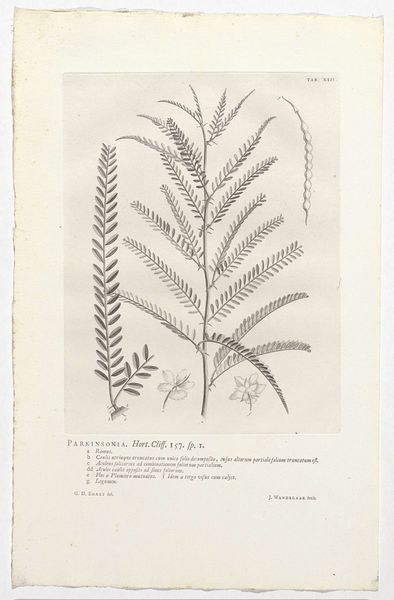

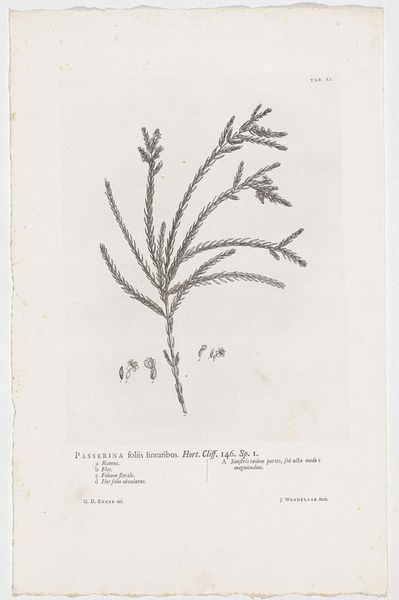

Editor: So, here we have Louisa Finch’s “Botanical Watercolours I”, created sometime between 1784 and 1820. It's a delicate watercolor and drawing on paper from a book. I’m struck by the almost scientific precision, and I wonder, what layers of interpretation can we find in something that seems so purely observational? Curator: Exactly! While seemingly a straightforward botanical study, we must consider the socio-political context of such artistic endeavors. In the late 18th and early 19th centuries, scientific illustration, particularly by women, intersected with colonial expansion and the classification of the natural world. Editor: Colonial expansion? How does that connect with a simple drawing of grass? Curator: Think about it: who was undertaking these botanical expeditions, and what power structures were at play? The very act of naming and categorizing these plants, often by European scientists, was a form of asserting dominance over the natural world and the lands from which they came. Where might Finch have obtained this particular specimen? Was it cultivated in England, or acquired elsewhere? What’s the significance of documenting nature during this period, and who benefitted most? Editor: So, it’s not just about documenting nature but about power and knowledge. The woman making the illustration…where does she fit in? Curator: Precisely. Women often contributed to scientific advancements, particularly in botany and natural history. Their access to formal education was often limited. This botanical drawing might signify both intellectual curiosity, a societal restriction, and a form of quiet resistance. Are women today also being overlooked or having their contribution limited? Editor: I hadn't considered those dimensions before. It’s fascinating to think about art as embedded within these layers of social dynamics. Curator: Indeed. Recognizing these nuances helps us move beyond surface appearances and prompts reflection on power, gender, and even our own position within ongoing global narratives. Editor: I definitely have a lot to consider. Thanks!

Comments

minneapolisinstituteofart about 2 years ago

⋮

These two albums of botanical paintings derive from what was once a 27 volume set depicting native plants of Britain. They were created by Louisa Finch, Countess of Aylesford whose maternal grandmother was the renowned naturalist and collector, Margaret Bentinck, Duchess of Portland. Lady Aylesford began the project in 1784, and when she concluded in 1818 she had painted over 2,800 botanical specimens. Many of these specimens she collected herself through fieldwork expeditions, but she also received hundreds of samples from an extensive correspondence network of experts located throughout Britain. Aylesford was widely respected in her day by other botanists, both for her scientific knowledge and her artistic abilities.

Join the conversation

Join millions of artists and users on Artera today and experience the ultimate creative platform.