drawing, print, engraving

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

baroque

# print

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 300 mm, width 195 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

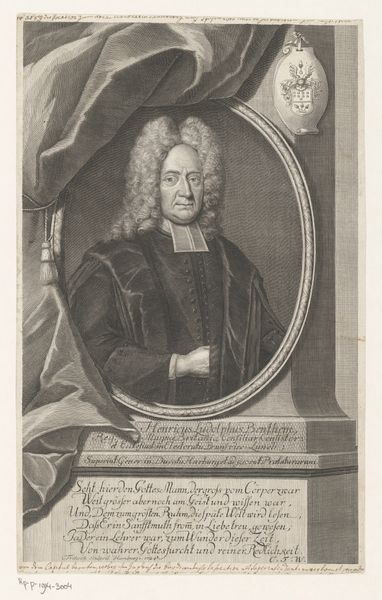

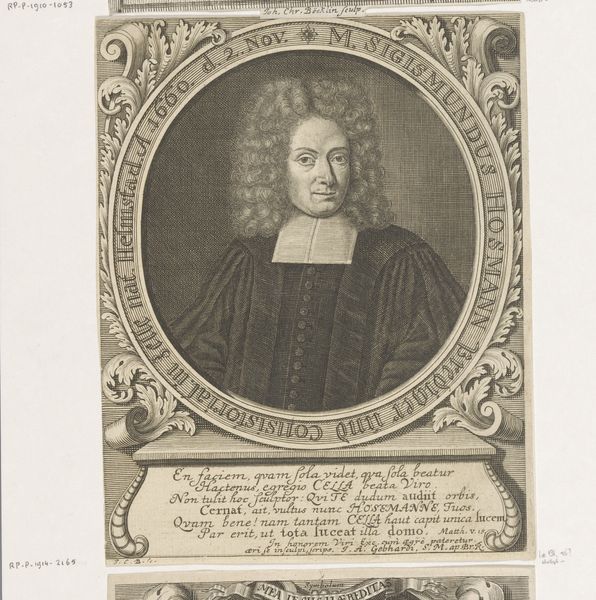

Curator: I find this print rather enchanting, a portal to another time. Don't you agree? Editor: It has a certain austere elegance. This is "Portret van Johann Baptist Rentz" created in 1703 by Andreas Matthäus Wolfgang. It's an engraving, offering us a glimpse into the Baroque era. But I immediately question who had access to such representations. Curator: Yes, it speaks volumes. The subject, framed within that strong oval, is certainly someone of considerable standing. The crisp lines and detail almost make him spring to life! I wonder, what was he really like? A stern fellow, perhaps, or secretly mischievous? Editor: The period's fascination with portraying status is very apparent. The crisp collar, the voluminous wig--these are symbols deliberately deployed. Note also the inclusion of his coat of arms. The power was often manifested through careful manipulation of such visual codes. It certainly invites us to critically engage with notions of identity. Curator: I feel a weight, looking into his eyes. Is it a sadness? Is it just the engraving’s style? And the text below – it’s almost hidden, as if a personal reflection slipped into an official portrait. There’s something quite human, trying to escape. Editor: You’re drawn to the individual, while I think the significance rests in considering it as a historical artifact. We must read through those "human" elements to access what this representation *meant* in its own time—a carefully constructed message about status and the existing structures of power. How might he represent himself, had he had full control over the artistic processes and narrative? Curator: Perhaps both interpretations coexist—the individual *and* the symbol—intertwined. That's how art breathes through time. I wonder how Johann himself would receive our chattering about him so many centuries later! Editor: Indeed. Questioning and considering all layers and meanings feels like the only responsible way to reflect upon the past—which in turn challenges our role within contemporary dialogues about power.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.