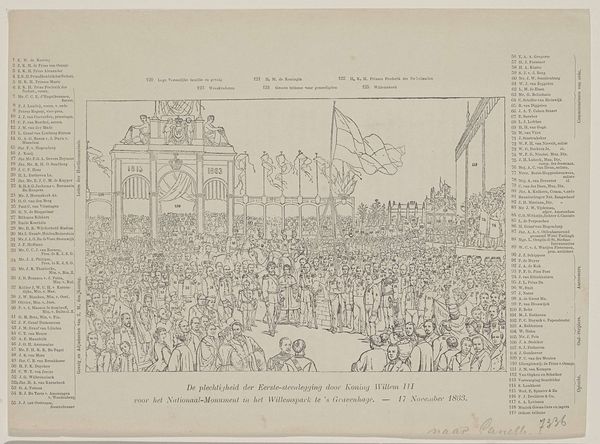

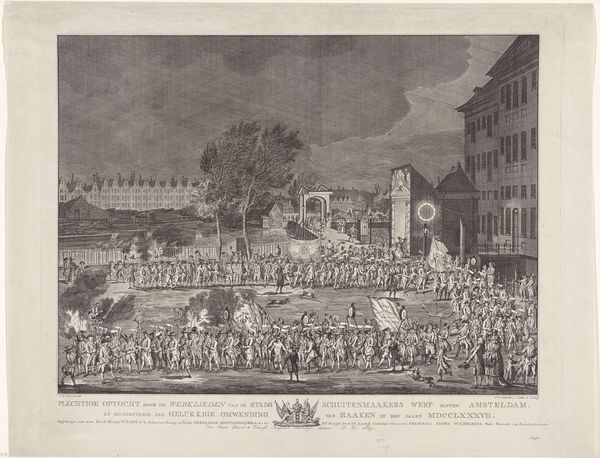

De plegtigheid der eerste steenlegging door Z.M. den Koning, voor het nationaal-monument in het Willemspark te 's Gravenhage, 17 November 1863 1863

0:00

0:00

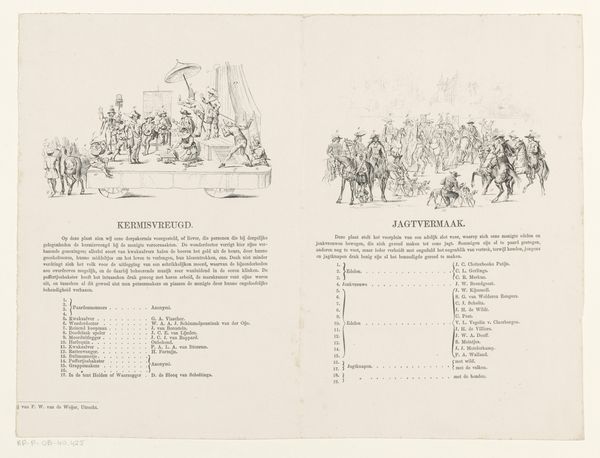

print, engraving

# print

#

old engraving style

#

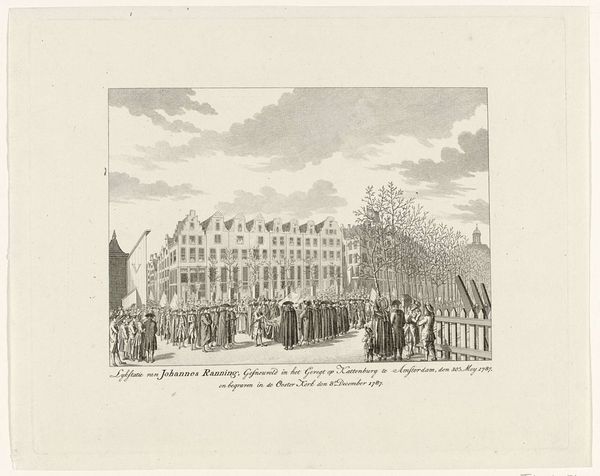

cityscape

#

history-painting

#

engraving

#

realism

Dimensions: height 400 mm, width 532 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

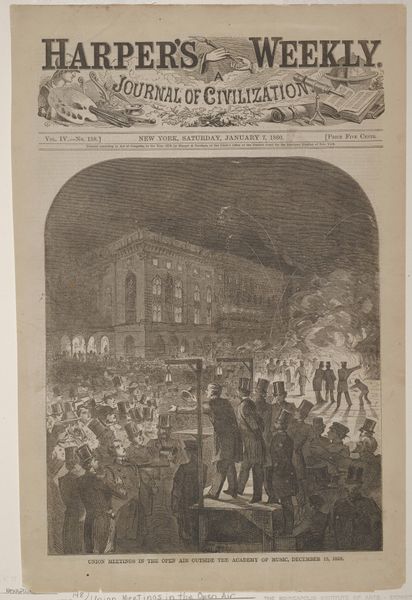

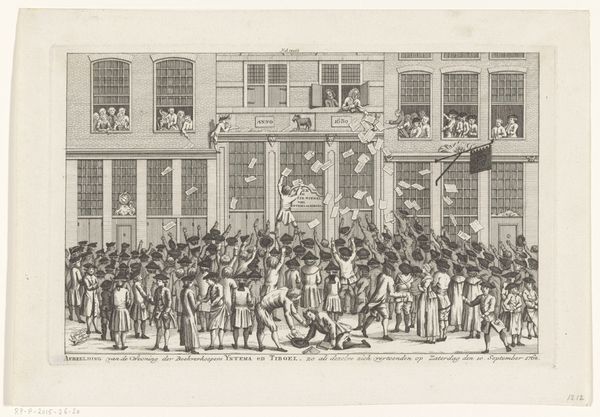

Editor: This is a print from 1863 titled "De plegtigheid der eerste steenlegging door Z.M. den Koning, voor het nationaal-monument in het Willemspark te 's Gravenhage, 17 November 1863" by an anonymous artist, an engraving showing a dense crowd and a formal ceremony. It seems like a record of a historical event. What significance might this event and its depiction hold? Curator: This engraving captures the laying of the foundation stone for a national monument, and to truly understand it, we need to situate it within the political and social currents of 19th-century Netherlands. This wasn't just about commemorating something; it was about forging a national identity. Look at the figures – who do you think is represented, and whose stories are left out of the frame? Editor: I notice the presence of what appear to be dignitaries but I don't really recognize anyone other than through titles that might identify their positions in government and military roles... Everyone depicted appears to be a man from what I can tell. Curator: Precisely. Who held power in that society, and whose perspectives were valued and memorialized? Understanding the context--such as the colonial past of the Netherlands--and how national identity was being constructed at that time, allows us to critically examine whose narratives were privileged, and which voices were systematically silenced in the construction of this ‘national’ memory. What does that tell us about whose stories are considered worthy of commemoration? Editor: It makes me think about the narratives that were pushed to the margins during that time, particularly considering the historical context of colonialism. This piece almost serves as a stark reminder of who held the power to shape national identity, erasing other experiences. Curator: Exactly. By questioning whose perspectives are missing, we can use this artwork to open up conversations about representation, power, and the complexities of history, moving towards a more inclusive and equitable understanding of the past. It becomes more than just a historical record, it's a site for critical engagement. Editor: I see it so differently now. It's more about uncovering hidden narratives and reflecting on how historical narratives continue to shape the present. Curator: Yes, questioning those narratives gives agency and restores missing perspectives to collective memory, enriching and expanding history, opening the way for truth and reconciliation in the present and the future.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.