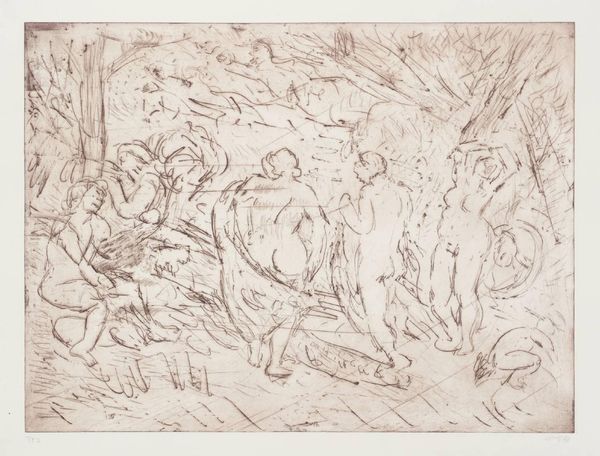

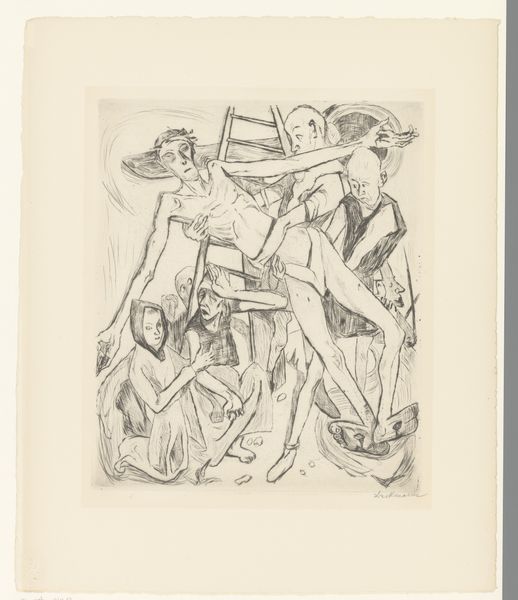

drawing, lithography, pencil

#

drawing

#

lithography

#

woman

#

narrative-art

#

german-expressionism

#

figuration

#

pencil

#

crucifixion

#

history-painting

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Let's take a look at Max Beckmann's "The Martyrdom," sheet three from his "Hell" series, created in 1919. The work on view at the Städel Museum, executed in lithography, drawing and pencil, seems to depict chaos. What strikes you initially? Editor: A sense of profound unease, honestly. The composition is incredibly dense; it’s a tangled web of limbs and sharp angles. The limited tonal range amplifies the feeling of claustrophobia and the overall violence of the scene. Curator: Indeed. Beckmann created this portfolio directly after his experiences in World War I. It represents the brutal reality of post-war Germany and the artist’s deep disillusionment with society. Look closely at the figures; they embody a spectrum of reactions from active violence to sheer terror. Editor: The formal elements absolutely convey that terror. Notice how Beckmann uses hatching to build up areas of intense shadow. These shadows obscure features, de-personalizing the victims and perpetrators alike. The distortions – elongated limbs and grimacing faces – push it beyond mere representation into raw emotional expression. Curator: Precisely! "The Martyrdom" wasn't just a personal catharsis; it served as a stark social commentary. Beckmann aimed to expose the hypocrisy and moral decay that permeated Weimar Germany. Its display at the time served to create an unsettling public awareness to the general moral and physical depravity. Editor: The spatial ambiguity is fascinating. We can't easily discern where one figure begins and another ends, heightening the overall feeling of confusion and entrapment. It makes me wonder about the nature of the violence—is it organized or spontaneous? Who are the victims? Curator: I think that is partly his point. In 1937, his work would be deemed ‘degenerate’ by the Nazis because they threaten the national identity they hoped to convey and build. "The Martyrdom" continues to resonate as a potent reminder of the consequences of social and political turmoil. It prompts us to confront uncomfortable truths about humanity and society, and I would contend it asks us still, even today. Editor: Absolutely. Beyond the immediate historical context, the power of Beckmann’s artistic treatment allows us to meditate on more timeless qualities. The density and compression makes sure the audience are forced to feel just as uneasy and tense. Curator: So, by using formal analysis, it offers a greater understanding to the context. I like that point of view. Editor: Thanks! And reflecting upon historical context provides an objective to assess compositional features, the success of its line work, and why certain moods may manifest more efficiently because of the historical significance.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.