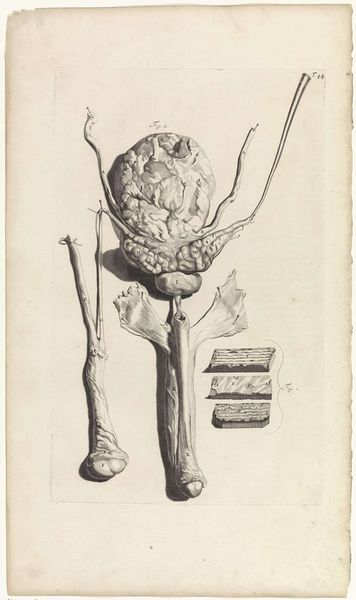

print, engraving

#

medieval

# print

#

old engraving style

#

figuration

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 140 mm, width 80 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

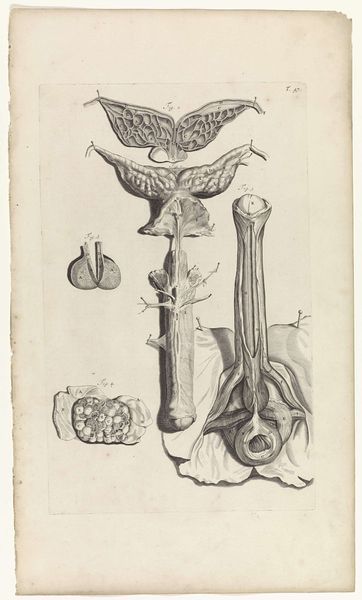

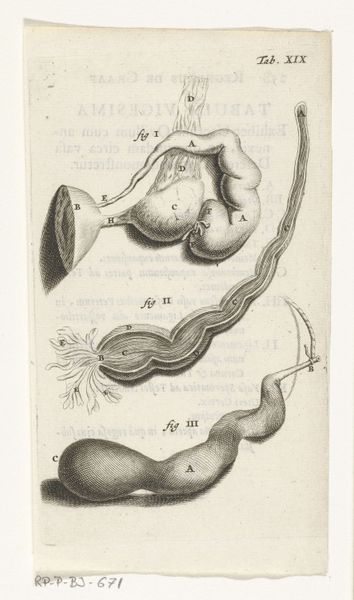

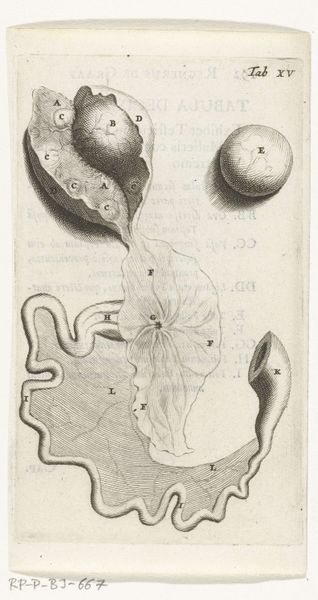

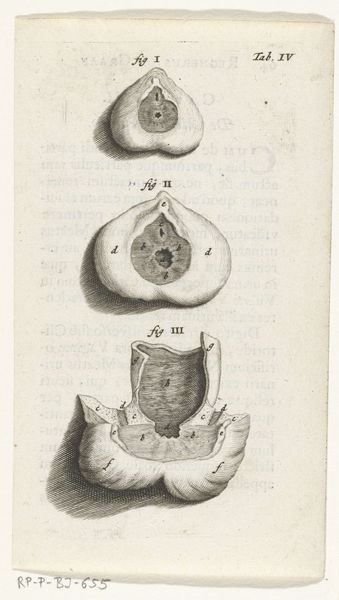

Curator: Here we have "Prints of the Female Reproductive Organs", an engraving made around 1672 by Hendrik Bary, now held at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: Whoa. Right off the bat, this reminds me of one of those old botanical illustrations... except instead of a flower, it’s, well, our insides. A little clinical but with a delicate, almost Victorian vibe in its detail. Curator: Yes, prints like these were incredibly important in disseminating medical knowledge at the time. Anatomical illustrations played a crucial role in medical education and scientific advancement, often circulating within scholarly circles and gradually informing public understanding. It's a tangible link to the history of medicine, reflecting societal attitudes towards the body. Editor: It's like a carefully arranged still life, albeit a somewhat surreal one. I wonder what the original intended audience thought seeing all those labelled little spheres. Ovaries maybe? And all those lettered bits... a code to unlock. The composition almost softens what could be, well, starkly scientific. Curator: The artist would have based the image on detailed observation and dissection and was part of the broader Dutch Golden Age fascination with empirical study and documentation. But it also hints at a broader discussion. Consider the limited perspectives on female anatomy and reproductive health available then – how was that medical knowledge being deployed or understood within broader patriarchal structures? Editor: Makes you wonder about the stories, anxieties and maybe even curiosities baked into producing, viewing, even possessing such images at this point in history. A collision of science, art, and cultural ideas about women's bodies, no? Curator: Precisely. That intersection is key. It reminds us that art isn't created in a vacuum; it reflects and influences society’s ideas about power, knowledge, and representation. Editor: Right. It strikes me now how images can shape our understanding of even the most private and personal aspects of ourselves. This print, despite its age, holds a mirror to that relationship.

Comments

rijksmuseum over 2 years ago

⋮

In 1672, physician and anatomist Reinier de Graaf published his De mulierum organis about the female reproductive organs. The book contains detailed prints by Hendrik Bary, among them several of the vagina. De Graaf was the first to conclude that a foetus was the product not just of a man’s seed, but also of a woman’s egg. He discovered what he called blisters, which later became known as Graafian follicles.

Join the conversation

Join millions of artists and users on Artera today and experience the ultimate creative platform.