Dimensions: height 226 mm, width 170 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

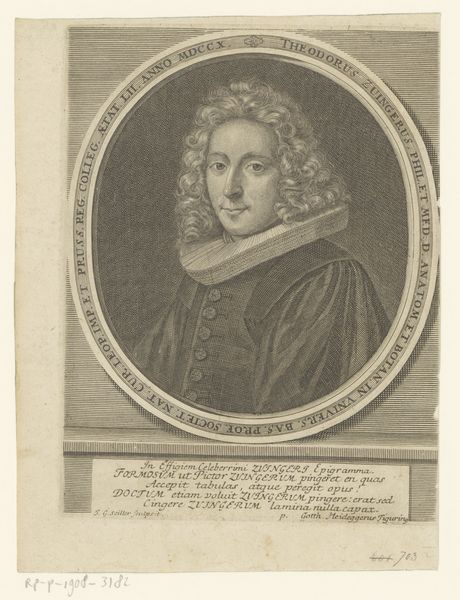

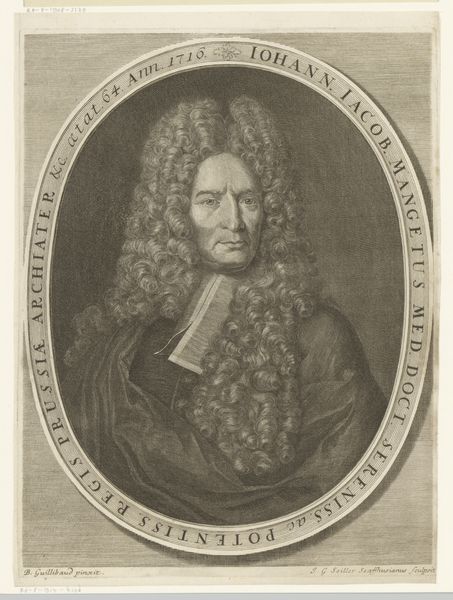

Curator: Let's delve into this engraving, "Portret van Benedict Pictet," created sometime between 1673 and 1740 by Johann Georg Seiller. What's your initial reaction to this portrait? Editor: Well, I notice its formality immediately. The oval frame, the inscription, and Pictet's pose—it all conveys a sense of authority. What's most striking is the sheer volume of his hair and robes compared to his face; it almost seems to outweigh him. What do you see when you look at this portrait? Curator: It's intriguing how the visual language employed constructs Pictet's identity. Think about the context. He’s identified as a theologian – how does this image function to legitimize his position within the societal hierarchies of the time? It's not just about representing him; it’s about reinforcing a specific understanding of power, knowledge and religious authority. How does that interplay with your reading of the face versus the garments? Editor: That makes sense. The text surrounding the portrait in Latin, mentioning he is a theologian and of Geneva at the age of 52 reinforces the sitter’s erudition and status, like credentials. But it's fascinating that his face seems rather soft and human within that context; almost a subversion. Curator: Precisely. And consider the Baroque era's penchant for elaborate detail. The clothing and hair aren’t simply decorative; they become a signifier of wealth, status, and a particular adherence to the styles dictated by the elite. How do you think contemporary audiences, confronted with very different signifiers of status, might interpret such a portrayal today? Editor: Today, I imagine those signifiers of status might come across as antiquated, perhaps even alienating. We value authenticity differently now; perhaps a more stripped-down or vulnerable representation might resonate more. Curator: Exactly. This piece becomes a valuable point for conversation, allowing us to scrutinize how identities were molded and projected in a bygone era, prompting critical reflections on our modern conceptions of self. I am glad we had this conversation. Editor: Yes, it's given me a completely different perspective. I hadn't considered the intersection of identity, status and power inherent in portraiture from that period. Thank you!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.