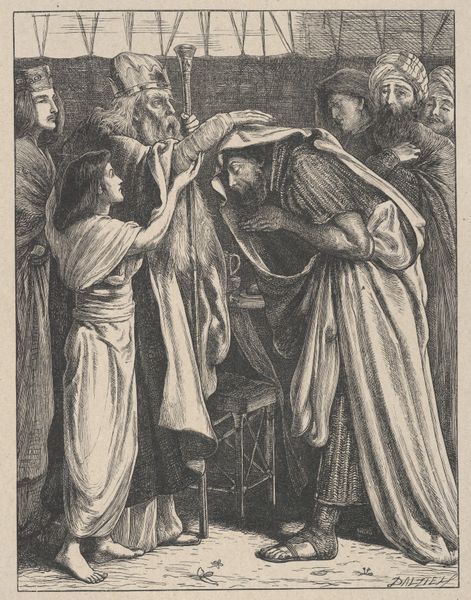

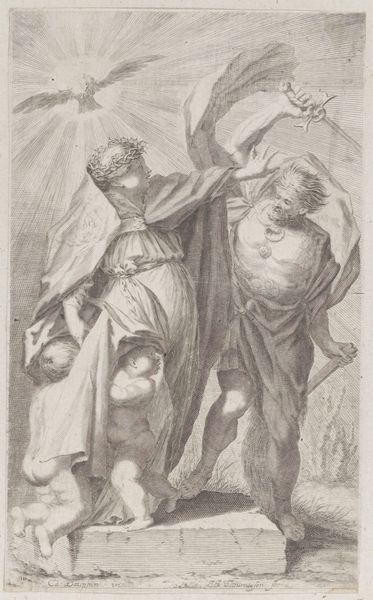

Eliezer and Rebekah, from "Dalziels' Bible Gallery" 1865 - 1881

0:00

0:00

drawing, print, engraving

#

drawing

#

narrative-art

# print

#

figuration

#

genre-painting

#

history-painting

#

academic-art

#

engraving

Dimensions: Image: 6 15/16 × 5 13/16 in. (17.6 × 14.7 cm) India sheet: 9 3/16 × 7 3/4 in. (23.4 × 19.7 cm) Mount: 16 7/16 in. × 12 15/16 in. (41.8 × 32.8 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Editor: This is Frederic Leighton’s “Eliezer and Rebekah,” a print from "Dalziels' Bible Gallery," dating between 1865 and 1881. I’m struck by the composition; the figures are so deliberately arranged, almost staged. What do you see in this piece? Curator: I see a Victorian fantasy constructed around biblical narratives, and as such, a powerful assertion of colonial ideals of beauty and power. Notice how Rebekah and the other women are rendered, classical figures framed within an orientalist setting. Leighton wasn't merely illustrating a bible story, but rather imprinting Victorian values of femininity and civilization onto an ancient tale. What power dynamics are at play, and whose gaze is being privileged? Editor: That's a very interesting point. I was focused on the aesthetics and hadn't considered the power dynamics. So you're saying this image, while seemingly religious, is also deeply implicated in colonial ideology? Curator: Precisely. Think about how images like these were disseminated: in bibles, art books, reproduced widely, shaping public perception not only of biblical stories, but of the ‘Orient’ and its inhabitants. The “Dalziels' Bible Gallery” provided an opportunity for artists like Leighton to frame biblical stories through a particular lens. What implications might that have? Editor: It almost feels like Leighton is using the biblical story as a justification for Victorian ideals of beauty and race. The women look so passively graceful; it feels less like a representation of the story and more like a commentary on the Victorian perception of the Middle East. Curator: Exactly. And that brings up key questions: Who is Rebekah in this narrative, and how has that understanding shifted over time, influenced by these visual representations? The image is a conversation piece, and the historical, cultural contexts allow us to challenge the singular interpretation it might initially propose. Editor: I see it so differently now! I’m going to remember that looking at the cultural background behind an artwork is essential. Curator: And remembering how it impacts us, even now. It's never just "art," it's always an intervention.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.