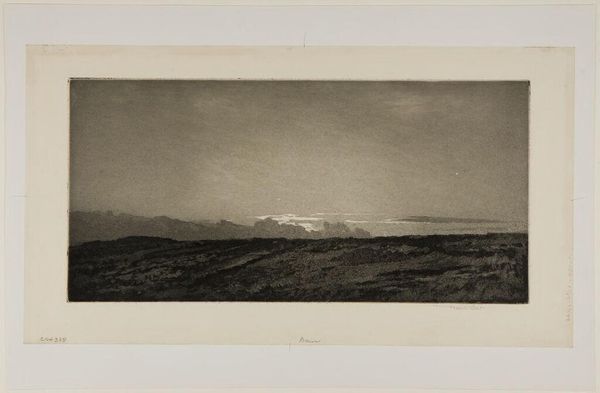

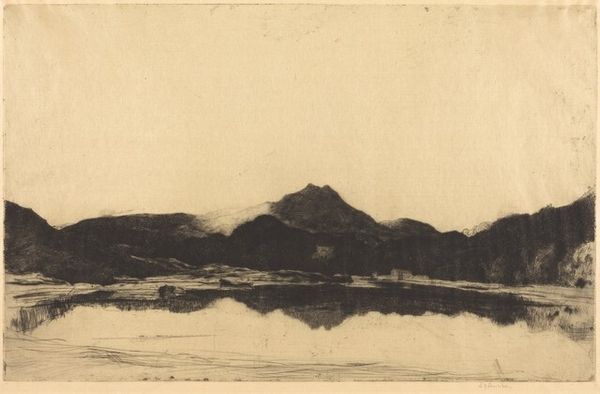

drawing, print, etching, paper

#

drawing

# print

#

etching

#

landscape

#

etching

#

paper

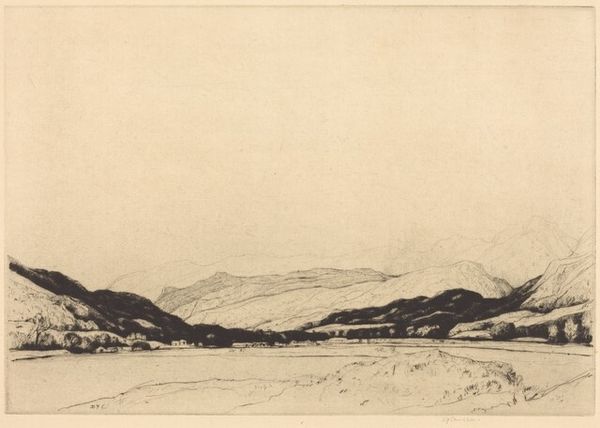

Dimensions: 175 × 302 mm (image/plate); 247 × 393 mm (sheet)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: What a wonderfully somber landscape. Editor: It is striking. You're looking at David Young Cameron's "Dinnet Moor," an etching from 1912, here at the Art Institute of Chicago. It’s a moody composition in blacks and grays. The heaviness in the sky really pulls you in, doesn’t it? Curator: It does, though the most remarkable thing is the tangible impression of the artist’s hand through the etched lines on paper. This level of intimacy would depend on the tools available. What sort of etching needles, acids, and paper would have afforded Cameron this unique expressivity? Editor: The etching medium was incredibly popular in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, really opening printmaking to a wider group of artists and audiences. Consider its role within the broader context of the art market at the time. Curator: Yes, these landscapes provided artistic consumption for a middle-class clientele, feeding their idealized visions of the Scottish countryside. Editor: Absolutely, but consider the image itself: there’s a quiet, brooding beauty in the way Cameron portrays the terrain. It speaks to something more than just simple consumption. This moor, etched in 1912, reflects anxieties towards encroaching industrial landscapes of the modern era and idealized notions of rural living in Great Britain. Curator: Do you see any visible texture? I imagine the type of paper used impacts the quality of that black ink, affecting its texture. What happens when the paper’s acidity compromises its long-term preservation? Editor: Of course. Every element—paper, ink, the biting process itself—contributes to our understanding. I also see it through the lens of institutional representation, of how Cameron’s art entered collections like this and how it's circulated and interpreted. Curator: Those dark lines really capture the wild beauty. An intriguing and complicated history brought to life through an engagement of labor. Editor: Right, it invites further contemplation about what we value and why we’re drawn to these landscapes even today.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.