#

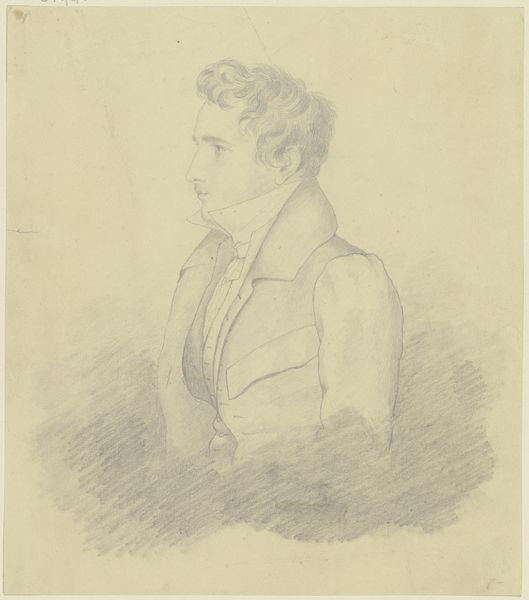

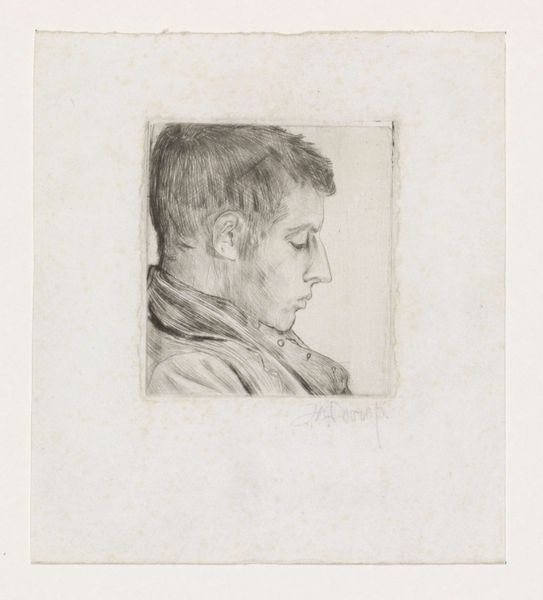

pencil drawn

#

amateur sketch

#

shape in negative space

#

light pencil work

#

pencil sketch

#

pencil drawing

#

portrait drawing

#

pencil work

#

tonal art

#

remaining negative space

Dimensions: height 189 mm, width 149 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

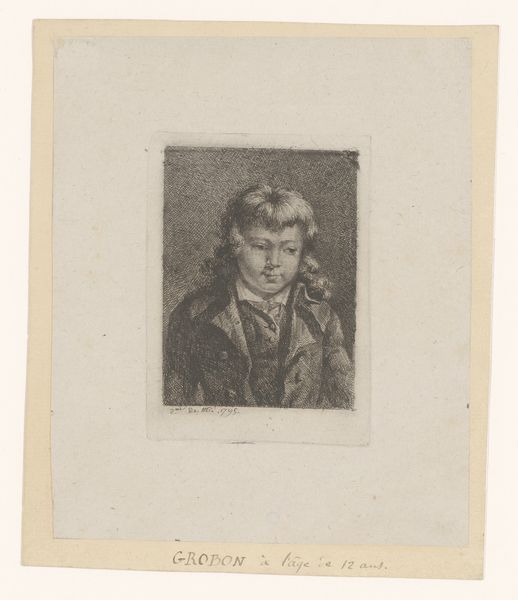

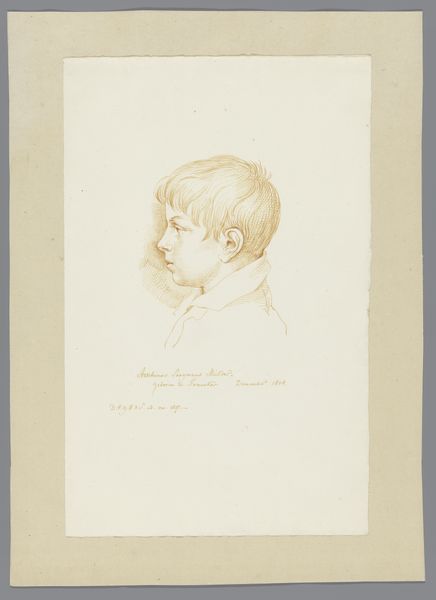

Curator: We're looking at a piece entitled "Portret van een jongen," or "Portrait of a Boy," crafted sometime between 1804 and 1859 by Benoit Taurel. It's a delicate pencil drawing, currently residing in the Rijksmuseum. Editor: It's stark, isn't it? Immediately, the intense, almost brooding expression strikes me. The light pencil work creates this ghostly effect, like he's caught between presence and absence. Curator: Indeed. It’s compelling to consider portraiture in this period, particularly drawings. Think about the role portraiture played in constructing social identities and preserving legacies. This wasn't just about capturing a likeness. Editor: Right, but who was this boy? Was it a commission, a practice sketch, a loved one? It evokes so many questions about identity, class, and even the power dynamics inherent in the gaze – who gets to be represented, and how? The remaining negative space further accentuates this sort of ambiguity. Curator: Precisely. The context surrounding such works is vital. Art academies, for example, emphasized life drawing, often involving anonymous models. These images reinforced prevailing notions of beauty, class, and power, reflecting who had the agency to commission or create such images. Was he posed, cooperative, or perhaps even coerced into sitting for this piece? Editor: And consider the act of sketching itself. The pencil work is quite intimate. We see the artist's hand, the slight imperfections. Was this intended for public consumption, or was it a more personal endeavour, a private reflection captured on paper? Curator: A valuable question, especially since the status and exhibition venues deeply impact our understanding. Had this portrait hung in a prominent salon, its reception would likely have been filtered through the lens of prevailing artistic conventions. Here, however, as part of the Rijkscollection, its merit may relate less to social status but still to canonic validation. Editor: Looking at it, I'm left wondering about the unspoken stories, the inequalities perhaps unconsciously mirrored in its creation. I do admire that its rawness seems so authentic and immediate. It's fascinating to have this direct access to art of a bygone age that can nevertheless encourage us to rethink our current society. Curator: A crucial point. The enduring value lies not only in appreciating the artist’s hand, but more importantly how we position it today within conversations around representation and access.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.