#

portrait

#

print photography

# print

#

archive photography

#

historical photography

#

historical fashion

#

romanticism

#

history-painting

Dimensions: height 470 mm, width 342 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

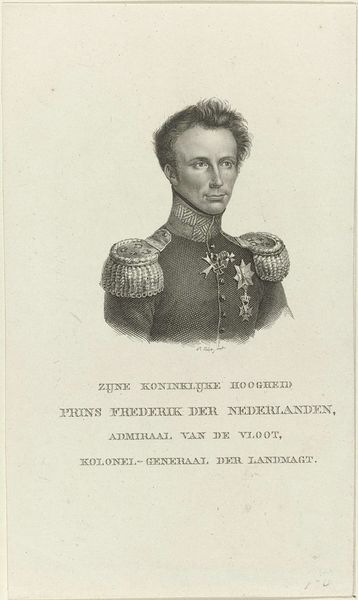

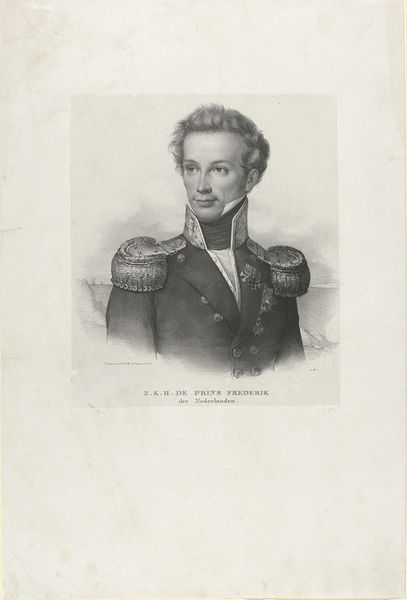

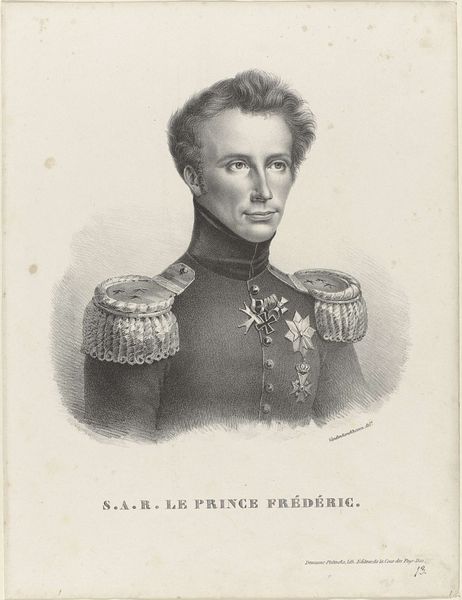

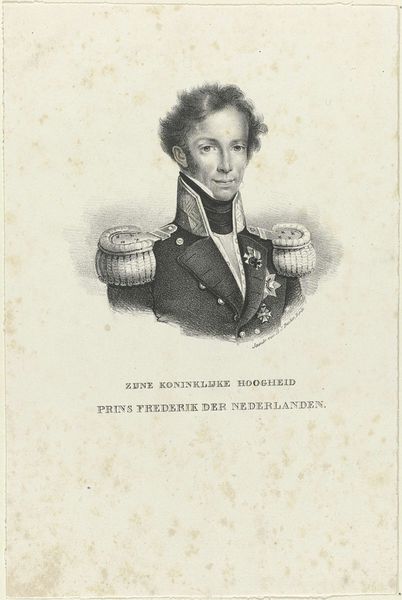

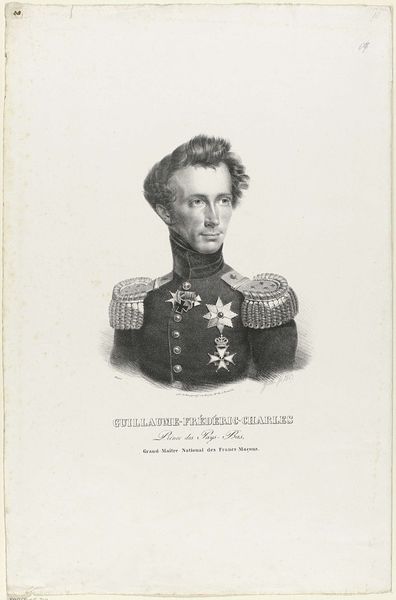

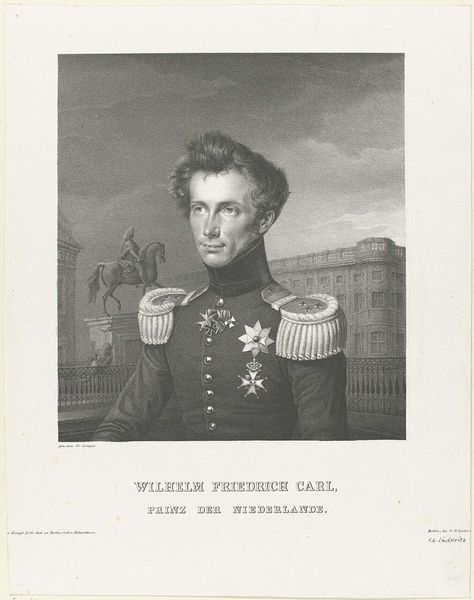

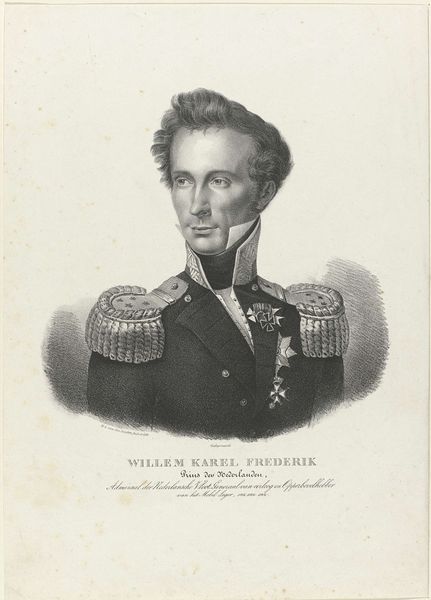

Editor: This is "Portret van Frederik, prins der Nederlanden," a print from sometime between 1827 and 1871, currently at the Rijksmuseum. He looks so formal in his military attire. I'm struck by the way the light emphasizes his face and those elaborate shoulder decorations. What can you tell me about its context? Curator: This print exemplifies how power was visualized and disseminated in the 19th century. Its creation and distribution are deeply intertwined with the rise of nationalism and the construction of a unified Dutch identity following the Napoleonic era. Editor: So, this wasn’t just about showing what the Prince looked like. Curator: Exactly. Think about it – this print would have been reproduced and circulated widely. How might that have served the ruling family, particularly in an era grappling with ideas of nationhood and popular sovereignty? Editor: It's a carefully crafted image designed to project authority and legitimacy. The symbols, the uniform… they all contribute to this image of a strong, stable leader. Was romanticism, which the artwork metadata mentioned, always associated with leaders? Curator: Romanticism wasn't always inherently tied to leadership, but it could be instrumentalized to construct powerful national narratives and associate leaders with particular values – think of the picturesque landscape behind him. Doesn't that invoke a sense of connection to the land, to the Dutch nation? Editor: It does. I guess I hadn’t really considered how prints like these operated as a kind of… propaganda, almost. Curator: In a way, yes. It reveals how images become active agents in shaping public opinion and solidifying social hierarchies. It’s a good reminder that what we see in a museum is often the result of complex political and social forces. Editor: This has made me rethink the role of portraiture in general. It's not just about capturing a likeness, but about actively constructing an image, a message. Curator: Precisely. By understanding the historical context and the social functions of images like this, we can gain a much deeper understanding of the past and its relationship to our present.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.