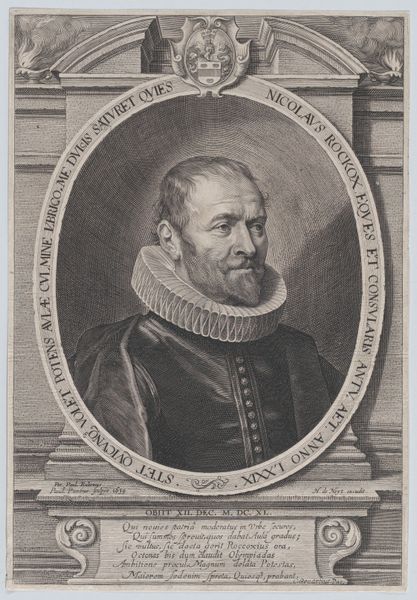

Portret van Maximilien de Béthune, hertog van Sully 1758 - 1806

0:00

0:00

jeanbaptistelucien

Rijksmuseum

print, engraving

# print

#

portrait reference

#

history-painting

#

engraving

#

realism

Dimensions: height 421 mm, width 275 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

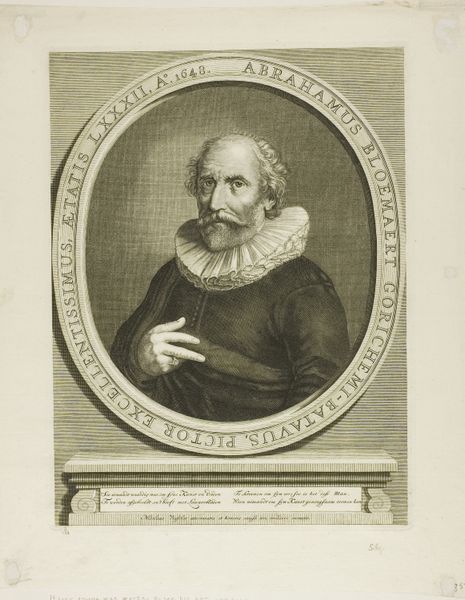

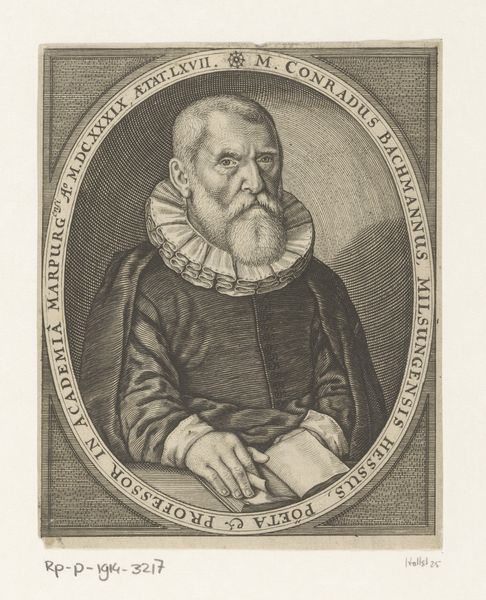

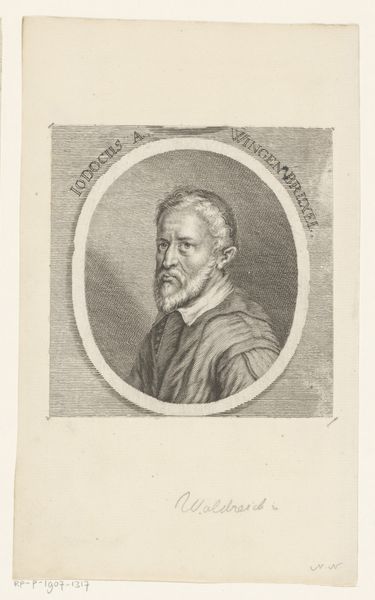

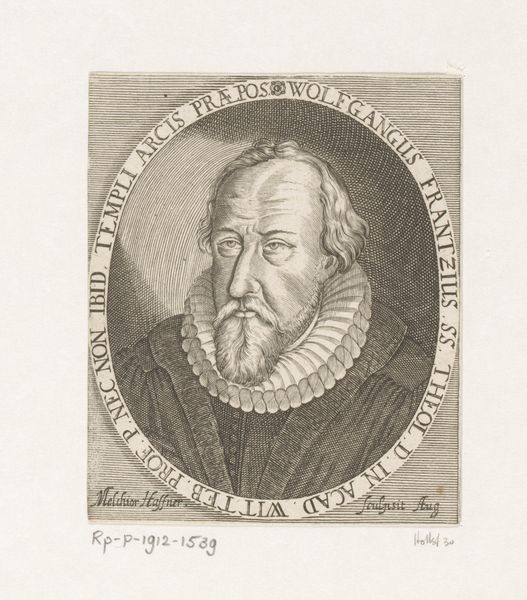

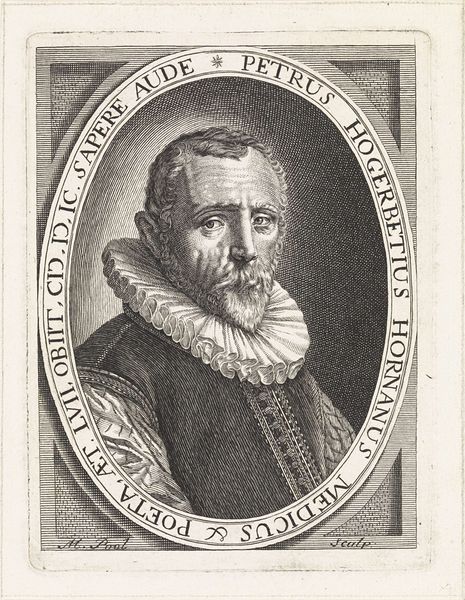

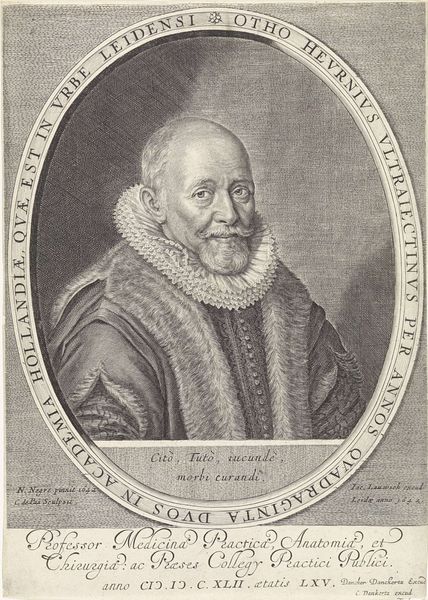

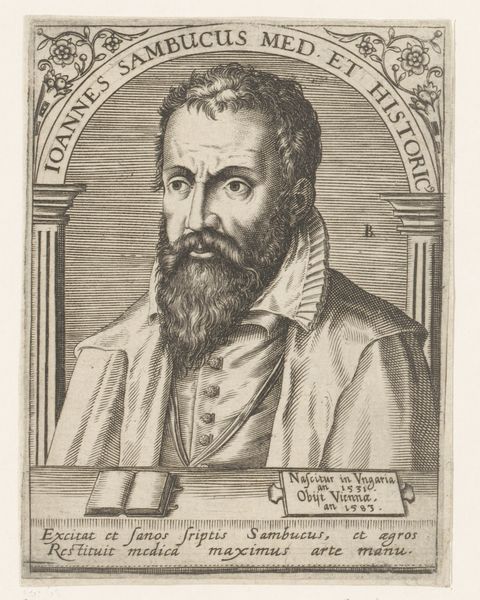

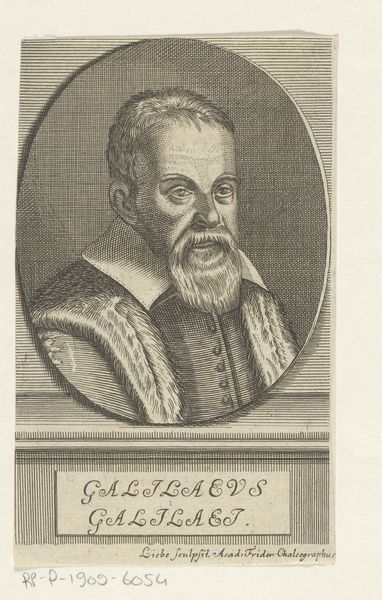

Curator: Here we have a print dating from 1758 to 1806, made by Jean-Baptiste Lucien. It's a portrait of Maximilien de Béthune, the Duke of Sully. Editor: Immediately striking. That elaborate ruff collar, almost consuming his face... it speaks to a specific moment in sartorial and social history, doesn’t it? Curator: Absolutely. The material aspect of that ruff, the probable linen, its intricate folds... it signifies status and labor. Consider the labor involved in creating, maintaining such a garment. Editor: Precisely! The image itself performs labor—depicting power. This portrait must have been circulated widely, fixing a certain image of Sully within the French consciousness and, perhaps, shaping the very notion of effective governance he was thought to embody. Curator: Yes, Lucien employed engraving techniques to recreate this image, making it reproducible on a mass scale. What statements could he then have been trying to make about history and the subject's perceived greatness, if any? Editor: We should remember, Sully himself occupied a fraught positionality within the French court, a Protestant advisor to a Catholic King, surviving numerous assassination attempts against Henri IV. So, this portrait potentially speaks volumes about religious tension and political negotiation during a period of turmoil. Curator: Consider also how the choice of engraving as a medium impacted the artwork's dissemination and accessibility. Cheaper materials allowed it to circulate in a way a painting couldn’t, thus reaching audiences of varying socio-economic status and creating a public memory. Editor: A potent, and reproducible, visual symbol crafted and consumed during immense socio-political strain. Even his eyes suggest a weary watchfulness, hinting at underlying tensions in his public duties during his long tenure as Superintendent of Finances and, later, as Governor of the Bastille. Curator: The material quality also suggests its intended use, for the study of history as a reference document in state institutions. How can prints reflect both intimate artistic processes while also forming something new, a historical or administrative tool? Editor: The question then becomes: How can we re-evaluate this artifact beyond the surface and recognize its role as both a visual and material witness to its complex social and historical circumstances? Curator: Absolutely, understanding these points helps reframe how we look at materials, their social lives, and these portrait’s legacies. Editor: Indeed. It grants this portrait fresh relevancy in understanding our present as built upon tangible connections between then and now.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.