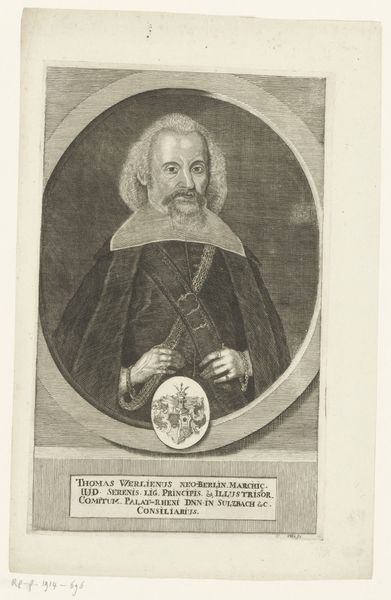

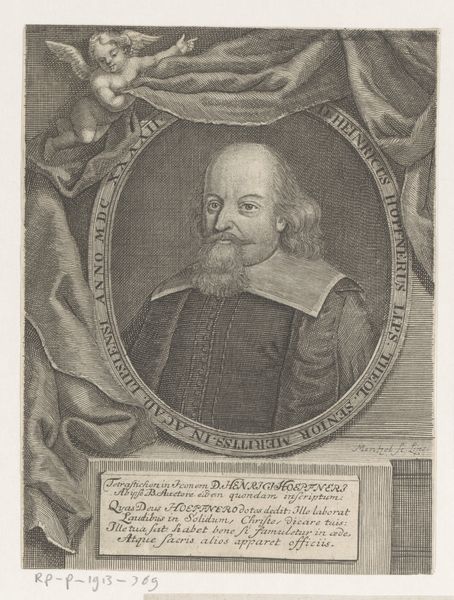

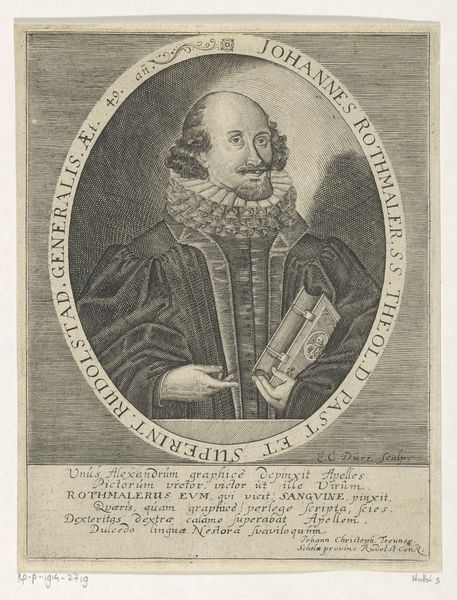

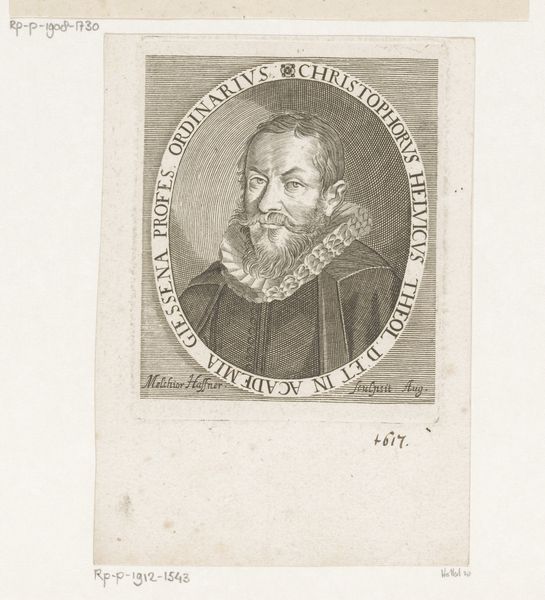

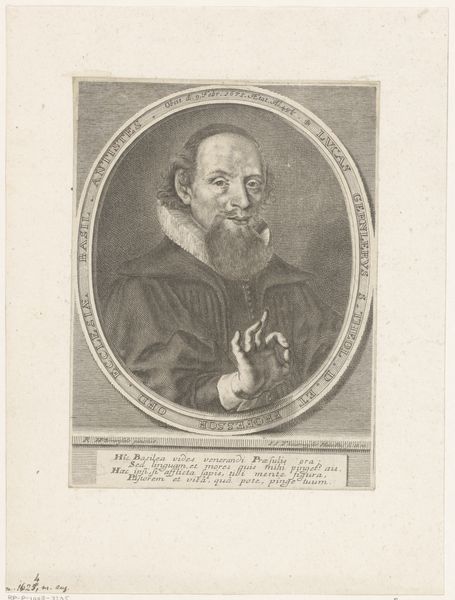

drawing, print, paper, engraving

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

baroque

# print

#

paper

#

engraving

Dimensions: 302 × 227 mm

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Let's consider this engraving, "Abraham Bloemaert," dating from 1648. The work is currently held at The Art Institute of Chicago. It was executed by Claes Jansz. Visscher after Bloemaert's own design. Editor: It's austere. The collar is stark, but undeniably impressive in its fine detail, and in strong contrast to the otherwise minimal execution of the image. Curator: The portrait is framed in an oval, which in turn is inscribed with text indicating Bloemaert's name and age. The figure's gesture seems to hint at an authorial direction. I wonder how it comments on notions of artistic legacy at the time. What can we interpret from Visscher selecting Bloemaert for rendition, given the nuances of workshop practices of that era? Editor: I'm struck by how the printmaking process itself dictates the image's qualities. The density of etched lines is striking, a deliberate material constraint impacting its texture and visual weight. And the choice to depict the man of labor at that time, given the broader historical moment for tradespeople and artisans is rather powerful. Curator: Indeed. Consider the socio-political landscape of the Dutch Golden Age and the evolving identity of the artist within it. How did engravings like these shape perceptions, build artistic reputation, or bolster commercial distribution? Editor: Absolutely. Moreover, let's examine the economic structures supporting this art form. Who were the primary consumers of such prints? To what extent does its reproduction reveal that moment of artistic dissemination to new audiences, given its materials were made for sale and mass distribution? Curator: These works often acted as both a form of documentation and an elevation of artistic persona. Visscher is engaging not just with portraiture, but actively crafting Bloemaert's image within the broader sphere of art history. Editor: And with its portability. Let's note the scale and implied use value embedded in prints versus, say, large paintings. What did prints allow artisans and their merchant funders to create as new consumerism options during the time? The use of paper itself democratizes representation. Curator: It leaves me contemplating the intersection of artistic agency and socio-historical narratives and their complicated intertwining through cultural values of their time. Editor: I agree; engaging with these kinds of objects invites a further consideration of their relationship with economics, labor, and historical context—reminding us of their complex means of creation and viewership, while in turn pointing out a critical and expanded material consciousness of their design.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.