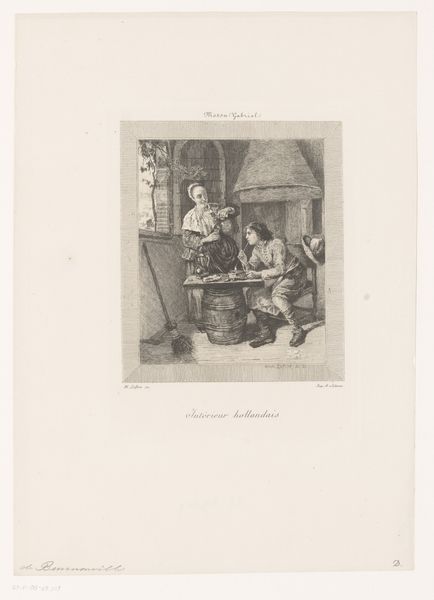

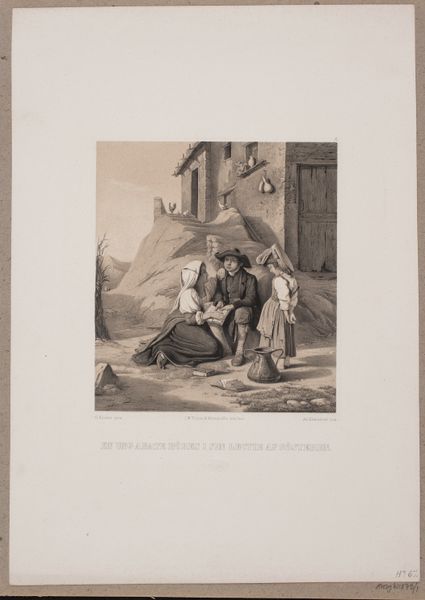

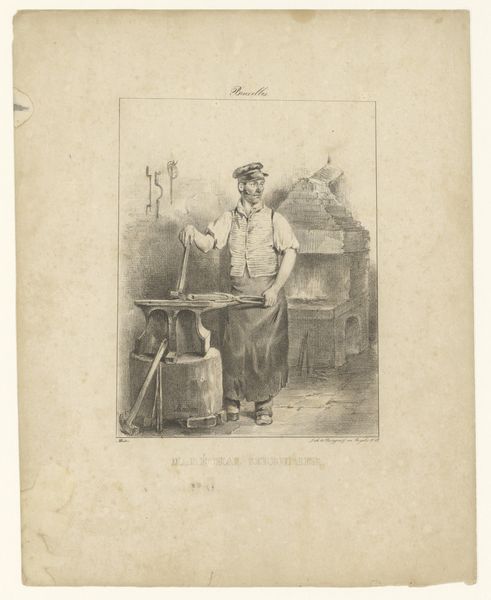

drawing, lithograph, print, paper

#

drawing

#

narrative-art

#

lithograph

# print

#

paper

#

genre-painting

#

realism

Dimensions: 400 mm (height) x 285 mm (width) (billedmaal)

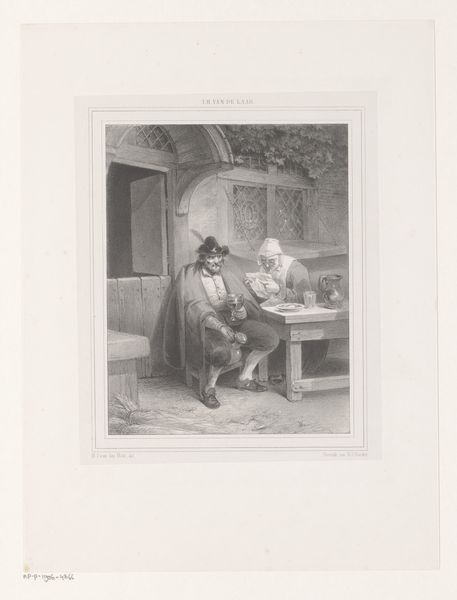

Curator: This is "En westphalsk bonde," dating back to the 1880s and created by Adolph Kittendorff. It's a lithograph on paper, housed right here at the SMK. Editor: My first impression is one of quiet observation; the enclosed space, the muted tones. The composition invites contemplation. The light focuses intensely on the faces. There’s a sense of profound, though perhaps melancholic, attentiveness. Curator: The lithographic process itself is key here. Consider the labor involved—grinding stones, meticulously applying ink, the skill needed to transfer such delicate details. The stark monochrome reflects limitations in access to material during the creation, no doubt influencing distribution too. Editor: Absolutely. And locating this image within its historical context reveals even more layers. Rural life in the late 19th century wasn't romantic. This man embodies the hardship, and the socio-political hierarchies prevalent at the time. You see a farmer but it also implies a system. Curator: Yes, the print medium was essential in disseminating such scenes beyond the elite. Its inherent reproducibility made art accessible to a broader public, potentially raising awareness of rural struggles. Think about the implications of these images entering public consciousness, challenging dominant narratives of wealth and prosperity. Editor: The father's pipe itself could symbolize comfort, escapism, even defiance amidst difficulty. The careful framing creates this space for a single moment of intense connection between generations - one weighed down by history, the other a still undefined future. And within this framework of gendered power dynamics. How are expectations forged and futures narrowed? Curator: I hadn't thought of that last point! But zooming out, how does this object exist today? The institutional context—a museum—inherently influences how we see it, don't you think? It almost neutralizes or certainly elevates something originally perhaps created to mobilize and democratize? Editor: Precisely. Seeing art, especially historical images, necessitates interrogating our own position and preconceptions in an increasingly digitized and hyper-connected world. What narratives about working class people are we perpetuating through the display, sales, distribution of historical artworks? Curator: An artwork’s life clearly extends far beyond the artist's intentions or its initial creation. I find this examination vital! Editor: As do I. Hopefully, our conversation sparks further contemplation about whose stories get told and how those stories reverberate today.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.