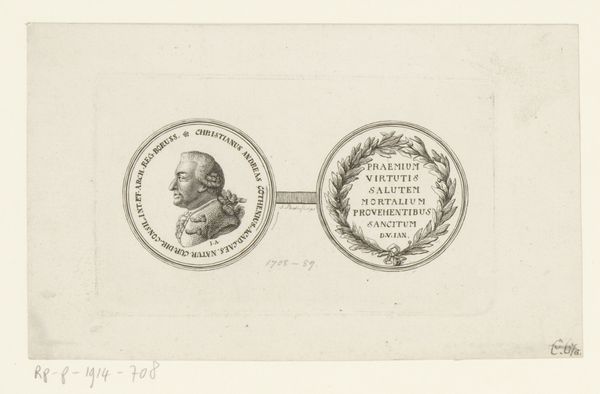

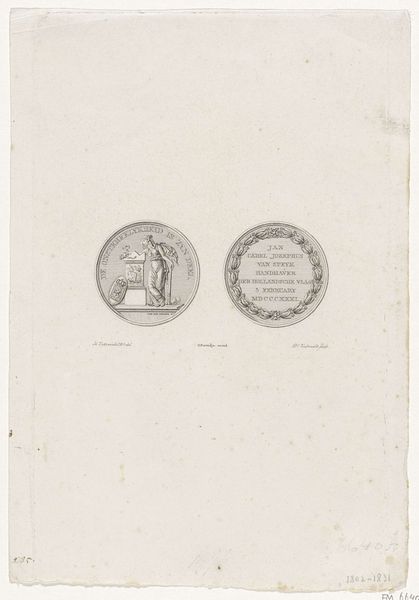

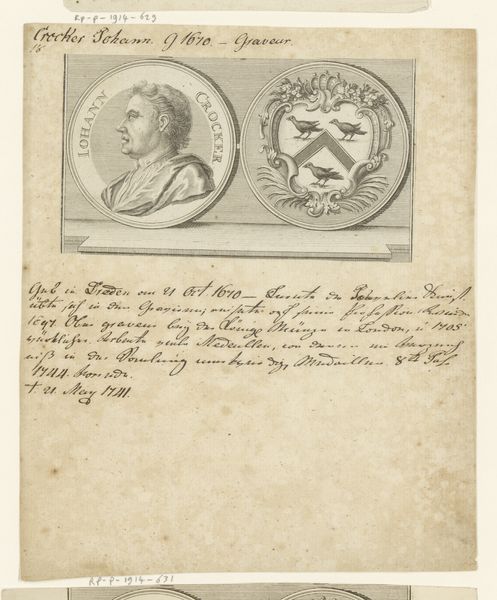

print, engraving

#

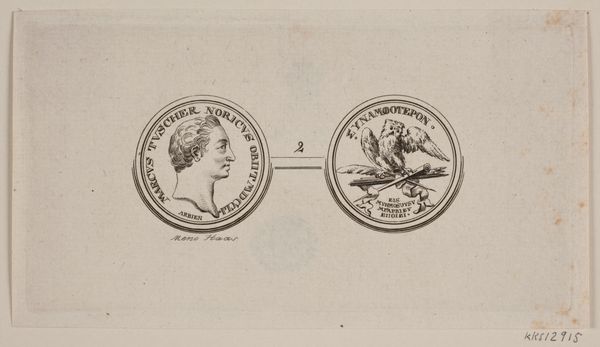

portrait

# print

#

classical-realism

#

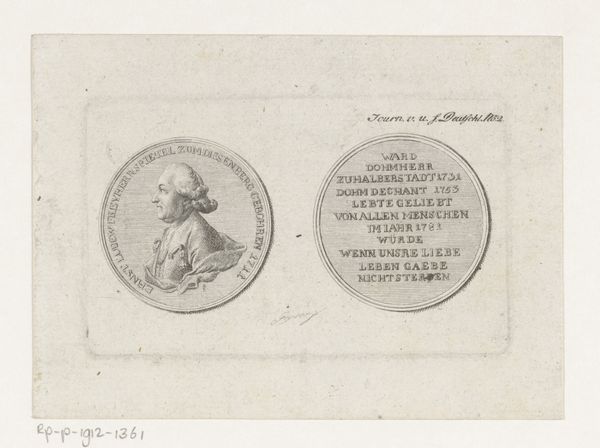

geometric

#

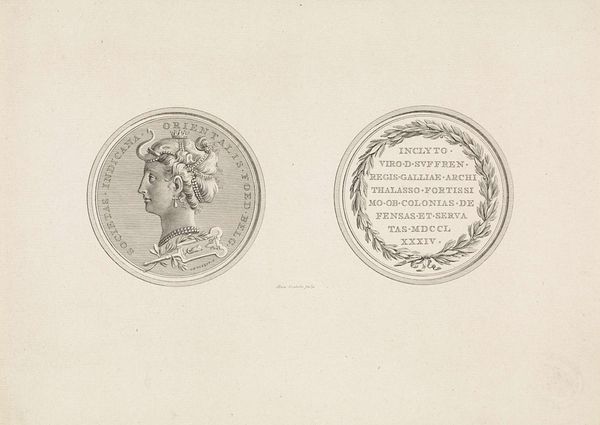

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: 75 mm (height) x 146 mm (width) (Plademål)

Curator: Let’s turn our attention to this engraving by Meno Haas, titled “Medaille. J. L. Holstein,” created between 1752 and 1833. Editor: My first impression is one of restrained elegance. The delicate lines and monochrome palette lend it a neoclassical sobriety, though something about it feels stiff, almost austere. Curator: That austerity is partly by design. This piece exemplifies the 18th-century interest in classical forms, a kind of revivalist mode meant to evoke virtue and order. It presents a portrait medal of Johan Ludvig Holstein. Medals like these functioned as markers of status, achievement, and memory. Editor: So it’s a form of early social currency? A way to circulate images of power and prestige amongst the elite? How does it function beyond pure portraiture, do you think? Curator: Precisely. The Latin inscriptions around the portrait certainly amplify that purpose. The text on the reverse side essentially dedicates Holstein as a 'friend of the king' and someone devoted to the muses. Note how that ideal links governance with intellectual pursuits. This piece almost idealizes Holstein within the established hierarchies. Editor: Yes, I’m struck by that interplay too. I see a careful orchestration of visual and textual elements, all designed to construct and disseminate a particular image. Though to modern eyes the somewhat florid praise might come off a bit…performative? Does it, perhaps unintentionally, reveal a reliance on image control and self-validation, as the ruling class seems very concerned with controlling the narratives and ensuring lasting influence? Curator: Interesting point! You’re right, in a sense, these medals serve as controlled biographical snippets circulating within a certain social stratum. However, engravings such as this were printed as keepsakes, to allow an easier distribution of that initial impression conveyed by an elite artefact, like a precious coin or medal. The work shows us how the aristocracy curated themselves and their histories through such commissioned works. Editor: Seeing it through that lens, this engraving goes beyond just honoring an individual, but the preservation and continuation of an elitist system by art. What could it suggest about art's wider involvement in social systems that maintain existing powers and ideals, not only in this time but today? Curator: A potent question and observation that demands that we reflect about our complicity even today. Editor: Indeed. Art challenges us to always question narratives and powers even if hidden or normalized.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.