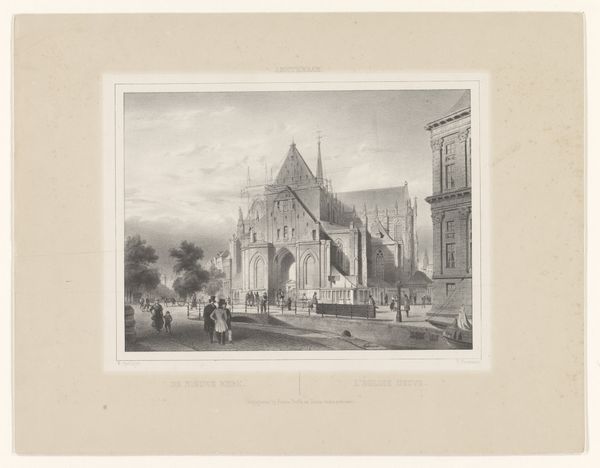

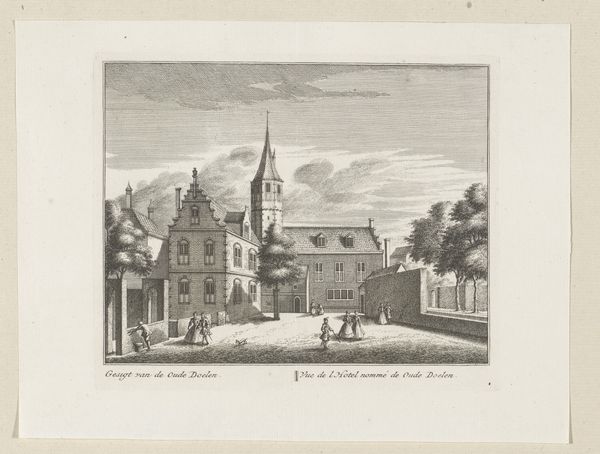

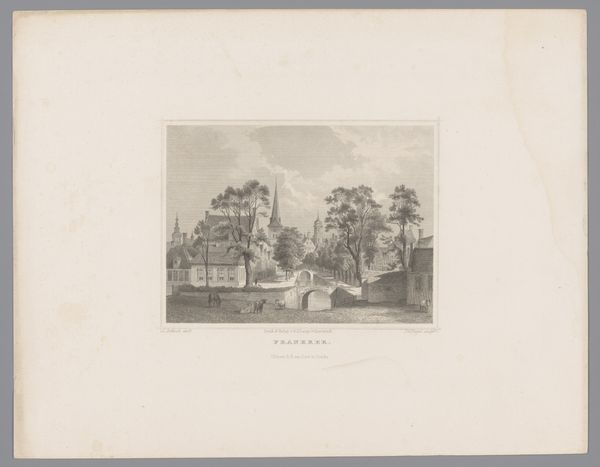

drawing, print, graphite, engraving

#

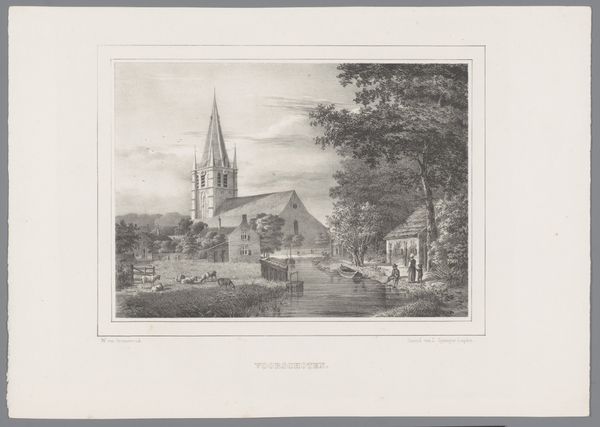

drawing

#

dutch-golden-age

# print

#

landscape

#

graphite

#

cityscape

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 290 mm, width 370 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Here we have Johannes Hilverdink’s “Stadswal met kerk en huizen,” a cityscape drawing, engraving, and print from sometime between 1857 and 1902. It depicts a city wall with a church and houses, offering a glimpse into the past. What is your initial impression? Editor: Stark and somber. The limited grayscale palette gives it a feeling of constraint, as if the city itself is holding its breath. Curator: It’s interesting that you perceive constraint. From an activist perspective, these city walls represent exclusion—who is kept out, and by whom? Walls have always been physical manifestations of power, deciding who is "in" and who is "out," impacting trade, cultural exchange, and individual freedoms. Editor: And yet the towering church implies the centrality of faith in people's lives at that time. Those twin spires almost pierce the sky, a potent symbol of spiritual aspiration, perhaps a counterbalance to that earthly, exclusionary barrier. Are we meant to interpret this pairing as a representation of competing authorities? Curator: The placement is definitely intentional. I see a conversation about social structure. Look at how the artist positions people on the road – small figures, almost insignificant under the gaze of the church and within the confines of the wall. How do those civic and religious structures determine identity and dictate accepted behaviour? Editor: There’s an intriguing mirroring effect between the wall’s height and the church’s positioning, which does suggest a visual dialogue about power and control. Those details also show us Hilverdink was likely knowledgeable of, or at least influenced by, period conventions. He uses symbols like architecture and figures as narrative cues to establish themes like religion and social stratification. Curator: Precisely. Analyzing the work through the lens of contemporary theory lets us investigate not only the symbolism, but the social context and power dynamics that shaped both the image and the reality it reflects. Whose stories are missing? How can we connect this 19th century image to present day concerns about inclusion, identity and political structures? Editor: By examining its historical visual vocabulary. That city wall, the towering church—they’re all testaments to cultural memory and lasting power. Curator: This work is much more than a pretty landscape – it's a historical and political document begging to be unpacked and critically examined. Editor: It is fascinating how enduring those archetypes are. It causes us to question what visual symbols are building *now* and what long shadow they're destined to cast.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.